In early March, at an anti-coup protest in Myanmar’s Karen state, a protester took a video of the police removing the placards and livestreamed it on Facebook. The video shows the police losing his patience and slapping away the protester’s phone.

The protester, however, was unfazed. He did not stop livestreaming. He asked the police, “What are you doing to me? While you use guns, why not we use phones? While you are armed, we [protesters] don’t even have [any] sharp tool to harm you.”

The protester is one of many Burmese citizens who have taken countless images and videos of the protests since the February 1 military coup. The military overthrew the civilian government over unproven claims of election fraud. It arrested senior leaders of the National League for Democracy party, including Aung San Suu Kyi. The demonstrators are demanding a return to the country’s nascent democracy.

Amid the climate of uncertainty, citizen journalists are shaping the narrative despite great risk. It has been reported that when military troops attack the protesters, the demonstrators shout, “Is there any media here? Please record what is happening.”

The work of Burmese citizen journalists is crucial, as the military junta has stripped five media operations of their licenses.

If no journalists are present, the protesters whip out their smartphones or cameras to document the violence or any wrongdoing committed by the authorities.

“Most of the footage of protests and crackdowns seen on the local and international media were documented by civilians,” said Zay Yar Min, editor-in-charge of Than Lwin Khet, a Yangon-based media outlet. “The emergence of citizen journalists has changed the media landscape,” he said. “They have become storytellers.”

The citizen journalists have used social media as the platform to reach a global audience. About 20 million Burmese are Facebook users.

Abusive response

The work of citizen journalists is crucial, as the military junta has assaulted press freedom in Myanmar. On March 8, the military-appointed State Administration Council (SAC) stripped five media operations — Mizzima Media, Democratic Voice of Burma, Khit Thit Media, Myanmar Now, and 7 Day News — of their licenses.

“These five outlets … have been at the frontline of providing extensive coverage of opposition to the coup and the abusive response of the security forces to ongoing peaceful protests,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch, in a statement. The police raided, searched, and destroyed some media offices.

Despite challenges under the SAC, media houses vowed to continue their works. After the SAC released the statement banning its media organization, Khit Thit Media released a statement, saying that its media agency registered officially under previous government and it will continue producing news.

Journalists cannot do their jobs without harassment, intimidation, or arrest. Many of them hide and change their locations frequently. Also, they “can’t freely travel to cover the news due to road blockades and insufficient funds, human resources, and equipment,” said Zay Yar Min.

Citizens are stepping up to fill the gaps in media coverage. They take photos and videos of protests throughout the country and livestream the content on Facebook in real time. Many videos secretly taken by citizen journalists, freelancers, and protesters, as well as footage from CCTV cameras, showed the military and the police brutally attacking protesters. These materials were widely shared on social media. Some international media used the materials in their TV reporting.

The content generated by citizen journalists greatly helps the media with their fact-checking efforts. Zay Yar Min finds their work invaluable. “It is faster to [confirm] fake news because they send evidence such as images and videos to us,” he said.

Keeping journalists safe

The civilians have gone beyond providing images, footage, and information to media houses. They also protect media workers from harm, said reporters and photographers covering anti-coup protests in the city of Yangon. Residents in many townships hide the journalists when the police chase them. Others help the journalists escape imminent attacks or arrests.

Phyo Lwin Aung, a multimedia journalist in Yangon, narrated how a local protected him while he covered the news in Tamwe township in the city. He was livestreaming, and the police ran after him. As he looked for an escape route, a resident opened the door of his home and let him in.

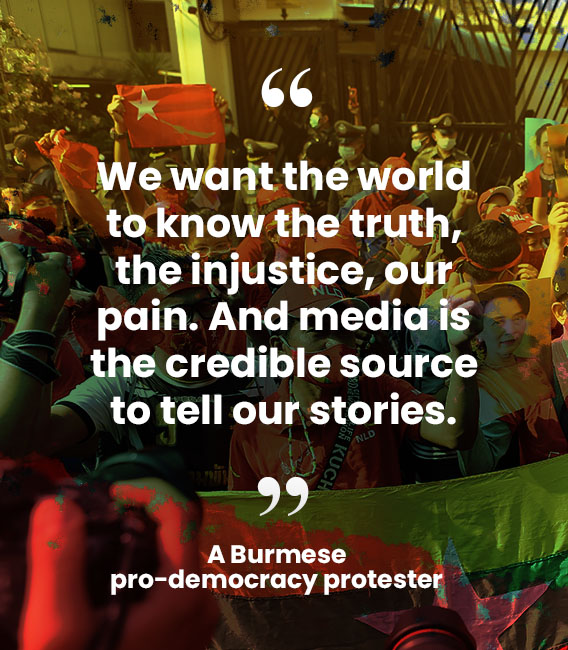

March 2021. Pro-democracy protesters take to the streets and prepare to resist police crackdown during the military coup in Yangon, Myanmar.

“I didn’t know him, and he didn’t know me,” said Phyo Lwin Aung. “[Yet] he gave me food and asked me to stay overnight at his place.” As the journalist could not go home due to the curfew, he gratefully accepted the invitation.

Zay Yar Min also shared a similar story. He was covering a brutal protest crackdown in the township of Tamwe. “I was in tears, and a Muslim family protected me,” he said. “They let me in their house and gave me food and water. They gave me a ride to my home.”

Several reporters and photographers also narrated stories of being protected by civilians. They said that they were helped by strangers during anti-coup protests.

Mutual protection

The resident who helped Phyo Lwin Aung believes that the media plays a vital role and deserves the protection of citizens. He said: “We want the world to know the truth, the injustice, our pain. We want the world to know how we are oppressed by the soldiers and the police. And media is the credible source to tell our stories.”

A male resident of North Okkalapa township in Yangon said that the presence of the media helps keep protesters safe. The protester said that it is when there is no media that the soldiers and the police attack them. He said: “We civilians fight for justice. We need the media [to keep us safe].”

North Okkalapa was the site of one of the most violent crackdowns on March 3. At least 18 people died in crackdown by security forces.

The military knows that the people have pinned their hopes on the media. They have arrested dozens of journalists.

Media experts have seen how media, citizen journalists, youth, protesters are united and closely cooperate in reporting despite challenges. Some media organizations invite individuals to send images, videos, and any evidences of abuses to them. Swe Win, editor-in-chief of Myanmar Now also posted on his Facebook wall, requesting individuals to send evidences of wrongdoing committed by security forces to his media house.

There has been a welcome change in the people’s attitude toward the media, said Zay Yar Min. Before, the civilians had little trust in journalists. During the coup, however, their view on the role of the media has changed. As security forces target and arrest media workers, citizen journalists play an increasingly important role. ●

Saw Yan Naing has written for The Irrawaddy, Bangkok Post, Asia Times Online, BBC Burmese, Global Investigative Journalism Network, and others. He is currently a technical lead and media trainer at Internews.

February 2021. The activists launched an app that allows people to scrutinize whether they are unintentionally spending money on businesses backed by a secretive conglomerate that funds the military. The conglomerate had a partnership with Japanese beer multinational Kirin – which the beer giant ended on February 5.

A digital arsenal

Aside from taking their anger to the streets, Burmese pro-democracy activists are targeting the army with apps “that aim to wreck their business dealings and keep people safe on the streets,” writes Burhan Wazir in The Daily Beast.

Myanmar’s military receives huge revenues from shares in Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited, according to leaked official documents analyzed by Amnesty International. The secretive conglomerate has interests in sectors ranging from banking to tobacco. It has partnerships with foreign businesses including Japanese beer multinational Kirin and South Korean steel giant POSCO. (On February 5, the beer giant ended its partnership with a brewery partly owned by military generals.)

Using the app Way Way Nay (translated as “Stay Away”), people can scrutinize “how they spend their money to avoid unintentionally financing the army and its supporters, who have investments in nearly every sector of Myanmar’s economy, from supermarkets to entertainment,” writes Tharaphi Than in her article. The app lists 250 companies, including banks, retail concerns, construction firms, media outlets, and health and beauty manufacturers with links to the military. Since its launch in February, the app has been downloaded more than 100,000 times.

Another app, Myanmar Live Map, takes real-time data from users to highlight areas with a high concentration of security personnel. The app, which has 40,000 users, also reveals the locations of water cannons, roadblocks, and ambulances. All the data is fact-checked by moderators before it is uploaded.

By Asia Democracy Chronicles