As lockdowns across Asia go from months to surpassing a full year, many with mental health care needs are falling through the cracks due to structural failures in funding and treatment.

Even before the pandemic, a combination of underinvestment and general neglect has left national health systems with little support for mental health. For instance, according to a 2016 analysis conducted by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations on its own member states, countries like Malaysia, Laos, and Brunei Darussalam had no identifiable national mental health care budgets.

In some cases, funding for mental health care was even bundled into funds for unrelated issues such as epilepsy and disease control.

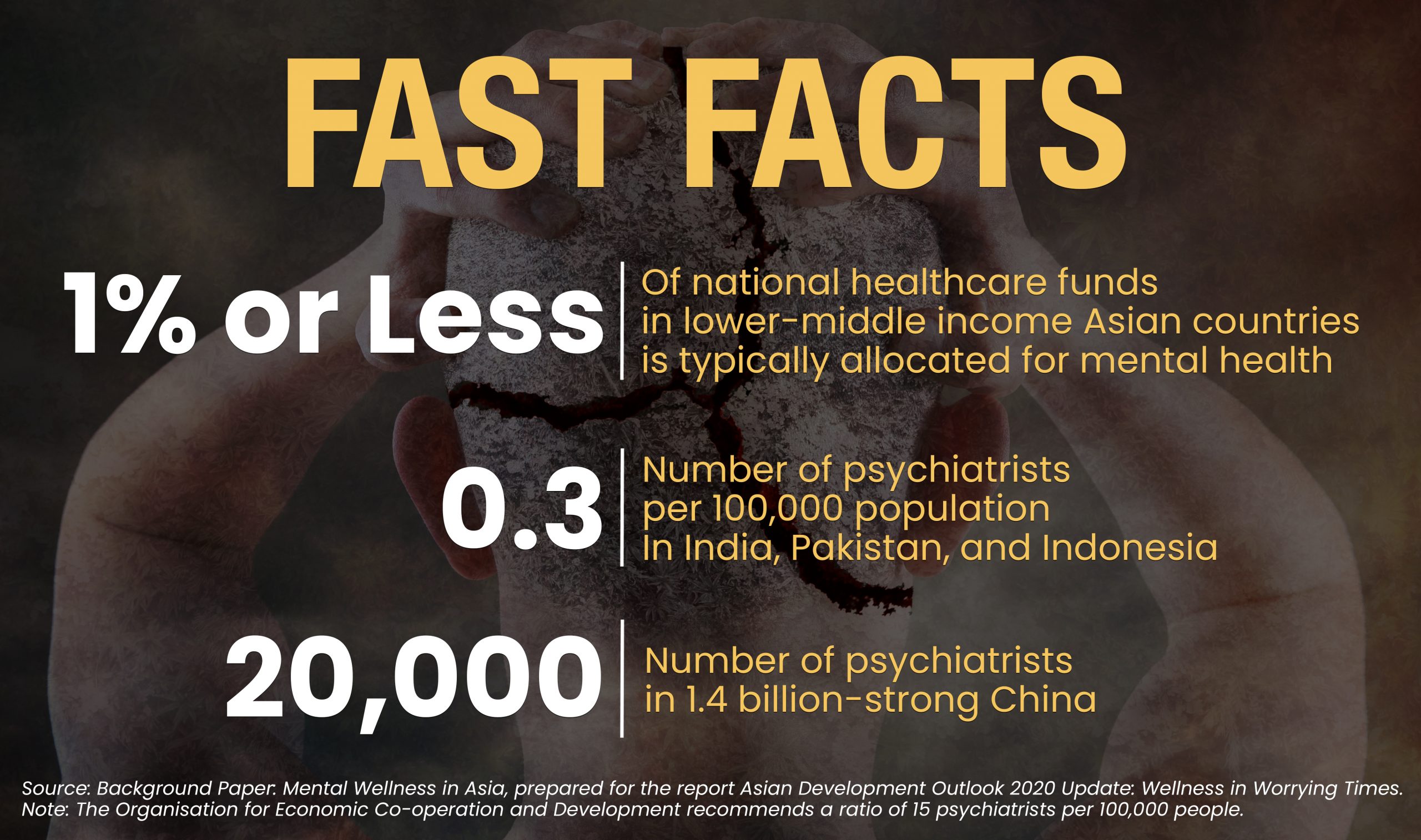

There are indications that the pandemic has made matters worse. According to a 2020 report from the Asian Development Bank, lower middle-income countries in the region face a collection of challenges, foremost of which is an inadequate number of mental health professionals. In places like India, Pakistan, and Indonesia, there are 0.3 psychiatrists per 100,000 people. In China, there are only 20,000 psychiatrists for the entire population of 1.4 billion.

These figures fall short of the standard from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which recommends a ratio of 15 psychiatrists per 100,000 people.

Navigating mental health services

Karlo Cleto has felt the effects of this shortfall first-hand. Since lockdown started in the Philippine capital of Manila in March of last year, he has had to navigate obstacles to get the mental health care he needs. At the start of the pandemic, his sessions were reduced to phone calls or text messages. But when his psychiatrist reopened her clinic around June, there were fewer slots for appointments, making it necessary to book way in advance.

“As you can imagine, this can be a scary proposition if you are in a bad place mentally and need help right away,” he said.

Cleto requires more upkeep than most. He suffers from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, and clinical anxiety, and takes a cocktail of mood stabilizers, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and anti-anxiety drugs. The protracted lockdown in the Philippines has not done Cleto’s mental stability any good. He says the pandemic has introduced new entries into his list of worries. Being vegan, he initially worried about whether he could buy food that fits his dietary needs. Later, he and his partner became concerned about their ability to make a living in a country that hit a record-high jobless rate of 45.5 percent in July 2020.

Because of social distancing measures, psychotherapy sessions were reduced to online consultations or through other digital means, which some mental health patients feel are an impersonal medium of care.

In spite of his need for care, Cleto mostly has been left to fend for himself, with limited support from the Philippine government or with his limited-purpose employer-issued health insurance. According to a 2020 report from advisory firm WillisTowersWatson, private insurance in the Philippines is nearly universal, with 99 percent of companies surveyed saying that they have private plans.

However, employer plans “very rarely” cover outpatient mental health services, and only 16 percent of hospitalization plans have coverage for treatments such as counseling, psychiatric care, and inpatient care.

“It’s ridiculous that these very serious illnesses are not included in the coverage of most policies,” said Cleto, adding that the introduction of government mental health subsidies would greatly improve his life.

Healthcare systems in disarray

Cleto is one of millions across the world who have experienced difficulties in accessing mental health services during the pandemic. According to a World Health Organization survey released in October 2020, most countries saw disruptions to their mental health systems, with many reporting delays in critical services.

The survey, which covered 130 countries from June to August last year, showed that 93 percent of respondent nations reported mental healthcare systems that were thrown into disarray or stalled altogether. Two-thirds of countries reported disruptions to counseling and psychotherapy. Meanwhile, 30 percent of respondent countries saw delays in access to medication for mental, neurological and substance abuse disorders.

“COVID-19 has interrupted essential mental health services around the world just when they’re needed most, said Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the director-general of the WHO. “World leaders must move fast and decisively to invest more in life-saving mental health programs — during the pandemic and beyond.”

For most of Asia, additional investments in mental health are very unlikely. According to the ADB report, lower middle-income countries in the continent such as India, the Philippines, Vietnam, Pakistan, and Indonesia typically allocate only one percent or less of their national healthcare funds on mental health. This is much lower than the already-meager global median spending of just two percent.

In spite of the heightened awareness of the need for mental health programs, there are signs that many countries are only offering lip service. According to the WHO survey, 89 percent of countries said that they have mental health support rolled into their COVID-19 response plans. However, only 17 percent of these countries have allocated additional funding for mental health.

Disruptions in mental health care due to the pandemic have been especially tough on the young and the elderly alike, who suffer from climbing rates of social isolation and systemic neglect.

There is an economic argument for investing in national mental health programs. For instance, estimates from before the pandemic showed that nearly USD 1 trillion in economic output is lost every year due to depression and anxiety. In India and China, this pattern holds, with mental health issues projected to cause USD 9 trillion in losses from 2016 to 2030.

Investments in mental health, on the other hand, have high yields, with every dollar spent on evidence-based depression and anxiety care projected to have a return of USD 5.

Additional investments become more justified when looking at long-term trends. According to the World Bank, GDP growth in the East Asia and the Pacific region excluding China is projected to expand to 4.9 percent this year and 5.2 percent in 2022. While this is an improvement from the contraction of last year, it is still 7.5 percent below the pre-pandemic era.

This drop in output is likely to have dire consequences. In the year after the Asian financial crisis in the late-90s, there were spikes in suicide rates among men in South Korea (45 percent), Hong Kong (44 percent), and Japan (39 percent).

“The economic disruption can be very troubling,” said Malcolm Hopwell, president of the Asian Federation of Psychiatric Associations. “We know that economic recessions are bad for mental health.”

Vulnerable population

Vulnerable population

As if things weren’t bad enough, Asia’s crumbling mental health infrastructure will have to contend with an expanding pool of mental health patients. According to the ADB report, places like South Korea, Japan, India, Thailand, Malaysia, and China have reported higher prevalence rates.

Across the Asia-Pacific region, the most common mental health problems are depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, suicidal behavior, and substance abuse disorder, according to data from the WHO and the OECD. The share of the population with major depressive disorders was at 20 percent in Thailand, 19.9 percent in Taiwan, 19.4 percent in South Korea, 17.5 percent in Malaysia, and 16.5 percent in China. These figures are much higher than the global depression rate, which is around four percent.

However, the strain from the pandemic has been heavier on some more than others. In some sections of the continent, there have been lasting damage caused to two vulnerable populations: the young and the elderly.

For senior citizens, who are at heightened risk of severe infection due to COVID-19, the pandemic has meant an atmosphere of anxiety in care homes, more time spent indoors, and less opportunities to stay active. This is an additional layer of loneliness from having children move away or the deaths of spouses.

“There is definitely a decrease in attention for the elderly in terms of the care at home. In older people, there is social starvation,” said Gundugurti Prasad Rao, president-elect of the Asian Federation of Psychiatric Associations and president of the Indian Association of Private Psychiatry.

The effects on children, meanwhile, have been more tragic. For instance, in Nepal, police reported a 40 percent increase in suicide among girls, according to a June report from the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund.

According to Hopwell, the typical composition of Asian families offers some, albeit modest, protection to the damaging effects of the pandemic. Multigenerational homes, which consists of three or more generations under one roof, are common in Asia, with people aged 65 years or older often living with children or extended family members. Hopwell said that such a living arrangement, especially during a time of crisis, can have positive effects.

According to Hopwell, the typical composition of Asian families offers some, albeit modest, protection to the damaging effects of the pandemic. Multigenerational homes, which consists of three or more generations under one roof, are common in Asia, with people aged 65 years or older often living with children or extended family members. Hopwell said that such a living arrangement, especially during a time of crisis, can have positive effects.

“Being with a group of people that you know care about you can be protective,” he said.

While it’s unclear when the pandemic will end in Asia, it is almost certain that there will be more pain over the coming months. Neglect and more contagious strains are causing COVID-19 surges in places like India, Japan, and the Philippines; and, as always, people living under the weight of grief and isolation will likely have to fend for themselves. ●

Christian Brazil Bautista has worked in the United States and the Philippines, reporting and editing for The Real Deal, Digital Trends, Financial Times, Real Estate Weekly, Yahoo! Southeast Asia, and Rappler.