By Chen Yi-Yeh, Chen Yi-Chun, Chan Hsiao-Yun, and Jhu Yuan-Cing

In over a year that SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, has conquered the planet, it has infected well over 100 million people and claimed more than 2 million lives. It has paralyzed countries, destroyed entire industries, and buried economies under crippling debt.

But the virus has also claimed countless livelihoods and sunk millions of people into unemployment and poverty, only serving to exacerbate the health and social inequalities that had been the sad norm in Indigenous communities.

According to a United Nations report, Indigenous communities have to contend with socioeconomic marginalization that puts them at disproportionate risk during public health emergencies. To COVID-19, Indigenous peoples are especially vulnerable.

“Indigenous communities already experience poor access to healthcare, significantly higher rates of communicable and non-communicable diseases, lack of access to essential services, sanitation, and other key preventive measures,” including those crucial to keeping COVID-19 at bay, such as clean water, soap, and disinfectants.

In cases where health facilities and services are accessible, Indigenous peoples will then need to overcome stigma and discrimination.

Taiwan is one of the few countries today that can still consistently claim victories against the virus. But despite having no large-scale outbreaks, public primary healthcare in its remote tribes has suffered.

Even in Taiwan, it seems, Indigenous communities continue to suffer from these same inequities, leaving them at high risk of infection as the rest of the country enjoys their relative safety.

Disease of deprivation

Taiwan is small. It covers less than 400 square kilometers of ground area and is separated from other states, potential sources of transmission, by bodies of water. Its geography, combined with its early action and strong quarantine protocols, helped Taiwan quickly became one of the world’s most prominent poster children for stellar pandemic control.

As of writing, its total case count remains below 1,000 with ten deaths, an amazing feat in a country of 24 million.

But such a seemingly spotless record belies important systemic health disparities, particularly between Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples and its Han Chinese population.

Due to a strong and sustained pandemic control protocol, Taiwan has been able to keep its COVID-19 case count to a minimum, and its people have returned to a relatively more normal life. But beneath this impressive track record is a healthcare system stacked against Indigenous communities.

According to the country’s Ministry of the Interior, the average life expectancy of Taiwan’s Indigenous peoples is nearly eight years lower than that of the national population, and infant mortality is nearly twice as high.

Dying from some of the most fearsome chronic conditions—cancer and diseases of the heart and liver—is also more common among Indigenous peoples.

Diabetes, which most Taiwanese consider to be a disease of wealth, is in fact more threatening among some of the country’s most deprived. According to the Annual Report on Population and Health Statistics of Indigenous Peoples, the mortality rate of diabetes among Indigenous communities is 1.6 times higher than that of the nation, and continues to worsen.

Some studies have also found that Indigenous peoples with diabetes are more likely to discontinue their medical care than non-indigenous people. They also seem to develop diabetes earlier than non-indigenous comparators.

Diabetes is a lifestyle disease. It arises from being overly sedentary or keeping greasy, sugary diets borne of affluence — or from being unable to afford to make healthier decisions.

Completely shut out

“I do everything that other people won’t do, because if I don’t, I won’t have money to live on,” says Xiuhua (not her real name), a Paiwan woman.

She said Indigenous peoples in Taiwan are often engaged in manual labor and often have to take on distasteful jobs to continue to provide for their families. Therefore, many jobs that carry the risk of infection, such as hospital cleaning, are performed by this segment of the population.

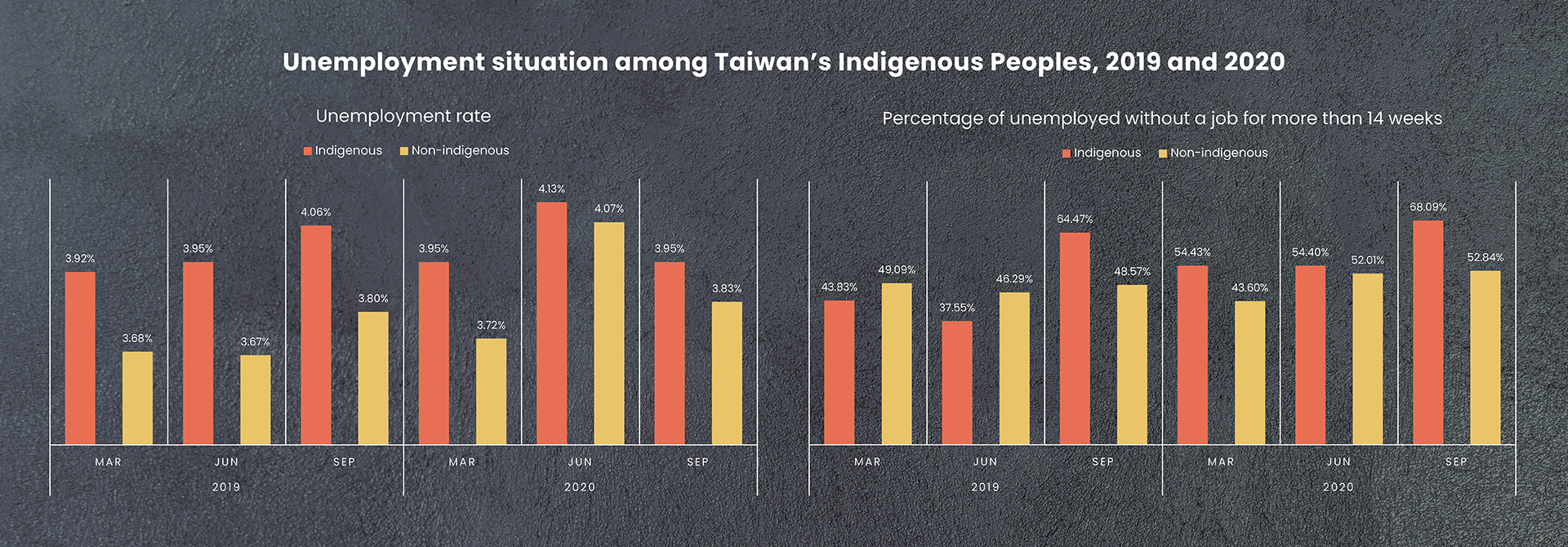

COVID-19 aggravated the already-poor economic state among Indigenous peoples. According to Taiwan’s Council of Indigenous Peoples (CIP), unemployment rates during the first and second quarters of 2020 were 3.95 and 4.13 percent, respectively, higher than the corresponding figures during the year prior.

As Taiwan increasingly brought the pandemic under control, Indigenous peoples saw slight socioeconomic improvements, and their unemployment rate declined during the third quarter of 2020. Nevertheless, the proportion of Indigenous peoples who had been unemployed for more than 14 weeks continued to rise.

Amid the pandemic, an unemployed person would have a much harder time finding a job if they were Indigenous.

Unemployment bears much more heavily on Indigenous peoples than on their non-indigenous counterparts. According to the 2017 Taiwan Aboriginal Economic Survey, salary accounted for 91.72 percent of the total annual income of Indigenous households, as opposed to only 34 percent in non-indigenous homes.

Losing a job, then, eliminates virtually all of the finances of Indigenous households. Unable to afford even the most basic necessities of survival, Indigenous peoples are completely shut out from the healthier, often more expensive, options.

Taiwan’s COVID-19 lockdown has intensified isolation and feelings of loneliness among Indigenous elders, who previously were able to gather at Cultural and Health Stations for Indigenous Long-Term Care.

Emotional and mental

But even beyond the economic and material, Indigenous peoples also have to deal with the emotional and mental.

Under normal circumstances, the government provides care and companionship services to disabled Indigenous elders through the Cultural and Health Stations for Indigenous Long-Term Care. But in 2020, these Health Stations became one of COVID-19’s victims, and its daily operations had been strongly affected.

“Normally, we can be present to remind our elders to take their medication on time. Now, we remind them by phone or home visits, but there is no guarantee they will do as we suggest,” says Ayu (not her real name), a care services specialist.

She says half of the seniors in the station currently live alone, and the station was closed for several weeks during the pandemic.

As a result, most the elders missed out on their weekly gatherings, cultural classes, recreational activities, and meals together, all of which had a significant impact on the physical and mental health of the elderly, and the treatment of their diabetes.

“Many seniors live alone and could have come to see each other every day, talk, share food and bond. This is important for their physical and mental health. Some people passed away during the closure period which is sad for everyone,” Ayu added.

Some physical and mental health programs have had to be suspended, affecting the elderly negatively. In addition, “Work assignments were rearranged, reducing the quality of services and time spent with the elderly,” she said.

A reversal of priorities

A reversal of priorities

COVID-19 revealed what should already have been obvious: There’s no getting around health inequality and misplaced priorities. The pandemic showed just how crucial it is to finally, genuinely, and sustainably fix a health system stacked against Indigenous peoples (and other marginalized communities), and to emphasize prevention over treatment.

In Europe and the United States, COVID-19 highlights the long-standing problem of public health systems of emphasizing treatment over disease prevention, drugs over diet.

In most countries, total health care expenditure is spent on end-of-life medical care, and only 2 to 6 percent is spent on health promotion, epidemic prevention, and other preventive, public, and group health-oriented public health services.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to sweep through the globe, it will only continue to bring to light socioeconomic and health inequalities against Indigenous communities. The only way to move forward is to radically change the systems and rebuild the structures that have grown so inaccessible, and sometimes even hostile, to this communities.

There is an urgent need to strengthen the resources and manpower, not only of Taiwan’s primary public health system, but also of its labor and social welfare services.

Only by holistically addressing these issues can Taiwan truly become a country where health is a basic human right and one that can strongly face emerging and resurfacing infectious diseases in the future. ●

Chen Yi-Yeh is the secretary-general of the Taiwan Association for Promoting Public Health.

Chen Yi-Chun is the executive director of the Taiwan Association for Promoting Public Health.

Chan Hsiao-Yu is a project specialist at the Taiwan Association for Promoting Public Health.

Jhu Yuan-Chung is a field researcher at the Taiwan Association for Promoting Public Health.

Over the past two years, unemployment rates have been consistently higher among Indigenous peoples in Taiwan. The COVID-19 pandemic has only worsened the situation, forcing more and more Indigenous peoples to be without work for longer periods of time. As a result, they have been unable to afford quality healthcare and better food choices, exacerbating the country’s already-glaring inequities in health. (Source: 2019 and 2020 Employment Situation Survey for Indigenous People, Taiwan’s Council of Indigenous Peoples.)