Late last year, in November, Afghan journalist, Bismillah Adel Aimaq barely escaped with his life.

In a Facebook post, he said that at around 11 in the evening, unidentified assailants sought to take his life, shooting at his car and throwing hand bombs into his house. His assassins were faceless and careless, and Aimaq survived, largely unscathed. He was even well enough to report the incident to security officials.

On the afternoon January 1, just as the promises of the new year were opening up to him, Aimaq again found himself the target of violence. This time, the hitmen didn’t miss.

Aimaq was driving when it happened. He had just finished visiting his family in the province and was on his way back to Firoz Koh city, the capital of Ghor province, central Afghanistan. All of his passengers, his brother among them, survived. Aimaq had been the clear target.

Aimaq was the former editor-in-chief of Voice of Ghor radio and was also a prominent human rights activist. He was 28.

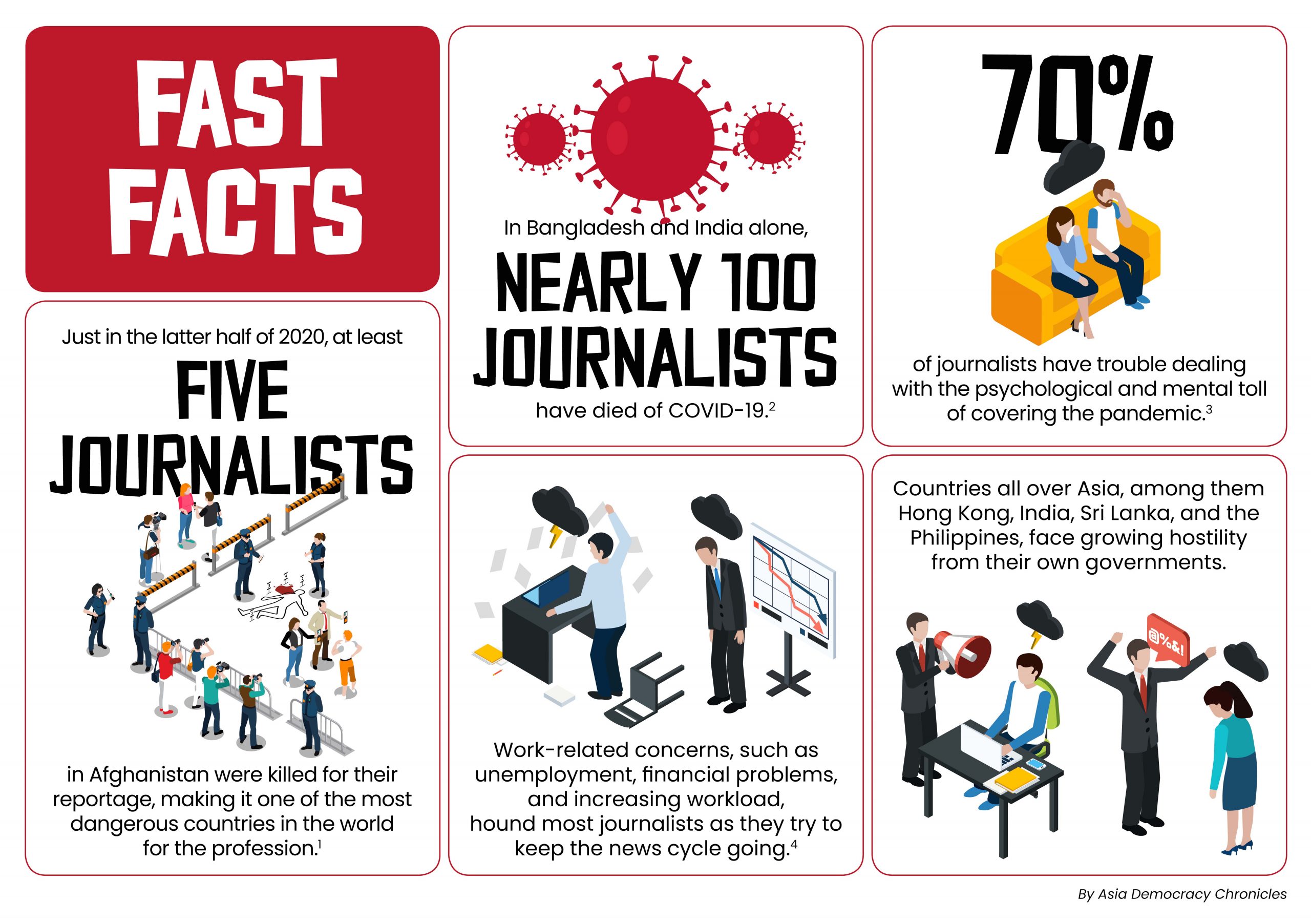

His death continued a deadly pattern for journalists in Afghanistan. In 2020 alone, at least five journalists were killed in the country as retribution for their work. According to Aliya Iftikhar, senior Asia researcher at the Committee to Protect Journalists: “The killing of Afghan journalist Bismillah Adel Aimaq is a tragic start to the new year and shows that the alarming increase in attacks on the media in Afghanistan is continuing in 2021.”

But the threat is present beyond Afghanistan, too. All over Asia, the media is hamstrung, not only by the movement restrictions due to COVID-19, but also – and more fatally so – because of the rapidly shrinking civic space, a swelling tidal wave of authoritarianism, and a seemingly endless deluge of disinformation.

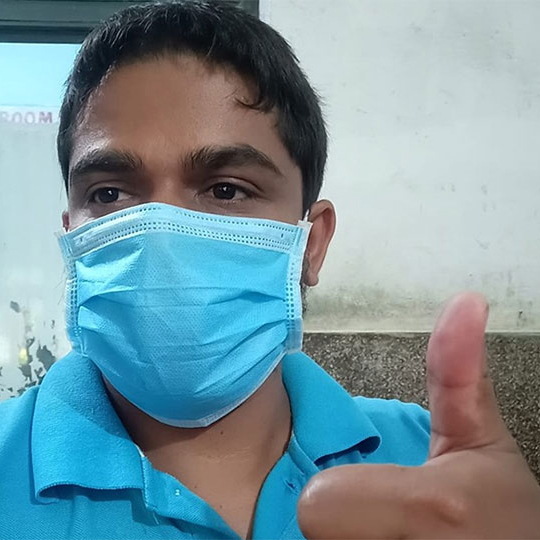

Suresh Bidari, Nepalese journalist, takes a photo of himself wearing a mask while in isolation. Due to the lack of reliable information about the pandemic in Nepal, he was forced to go out into the field to report, and was infected with COVID-19 as a result. (Photo by OnlineKhabar)

Occupational hazard

On all three fronts, the media has a crucial role to play. Keeping the people informed, after all, is keeping them empowered. But the human bodies that keep the wheels of journalism turning are themselves susceptible to the pandemic. This has turned even the most basic techniques of information gathering into occupational hazards.

The Press Emblem Campaign is a Geneva based press freedom organization that has been tracking COVID-19-related deaths among media workers. They have found that since March 2020, at least 655 media workers have perished due to the disease. In India and Bangladesh close to 100 have died.

Media organizations have taken it upon themselves to look after each other. Last year, the Nepal Investigative Multimedia Journalism Network (NIMJN) gave out personal protective equipment to journalists in Nepal who had to go out to report on the pandemic and other stories.

According to Rajneesh Bhandari, an international multi-media journalist and head of the NIMJN, government officials used the constricting atmosphere of the pandemic to their advantage to shield information even more. He said that government officials stopped or delayed releasing timely information to journalists, and made themselves scarcely available for interviews or to answer questions.

“It was difficult for journalists to report and get information in the field. Many government officials took the pandemic and physical distancing as a reason not to meet journalists and share information,” Bhandari said.

This left journalists like Suresh Bidari of Nepal with no choice but to brave the pandemic in search for authentic, accurate information about the pandemic from reliable sources. “I have not compromised my responsibility even if it means to risk my own health,” he said.

Eventually, however, COVID-19 did catch up with Bidari. (He survived the disease.)

Beyond the physical, journalists also have to endure the psychological. In a recent survey by the International Centre for Journalists, over 70 percent of respondents said that they had trouble dealing with the mental impacts of covering the COVID-19. In particular, nearly half of the participants had aggravated anxiety. Exhaustion and burnout, a sense of helplessness, and difficulties sleeping were also common emotional responses to the pandemic.

The report also found that the majority of journalists contended with unemployment and other financial impacts wrought by COVID-19, as well as heavier workloads and the difficulties of social isolation.

“Many became jobless,” NIMJN’s Bhandari said. “Many weren’t paid on time and media outlets didn’t give enough support and care to those reporting in the field.”

A woman wears a mask in support of media giant ABS-CBN’s franchise renewal. On May 5, 2020, the Philippine congress, empowered by President Duterte’s rhetoric, denied the petition, and the station was forced to cease operations. It remains off-air to this day.

Rougher times ahead

More worrying, however, are the extreme existential threats facing journalism at large. The year 2020 played witness to governments across Asia clamping down hard on the free press.

Hong Kong, for example, was put in a chokehold by the mainland. After the national security law was strongarmed onto the special administrative region in June 2020, several key media figures, democracy activists, and opposition politicians were taken into custody. Others, still, were forced to seek refuge abroad.

The press is under siege in South Asia, too. In India, between March and May 2020, 55 journalists “faced arrest, registration of first information reports, summons or show causes notices, physical assaults,” due to their reporting linked to the pandemic, according to a report by local human rights think-tank Rights & Risks Analysis Group.

Sri Lanka, on the other hand, has had to face a more restricted cyber space. The government has announced that it was exploring means to monitor and control online content on social media, Facebook in particular, ostensibly to curb hate speech and disinformation.

Human rights groups have warned that the island nation’s human rights situation was already perilously placed as it entered its second year battling the pandemic.

The Philippines has seen what is arguably the most brazen attack on the media in decades. On May 5, 2020, one of the country’s biggest broadcast networks, ABS-CBN, went off the air after its franchise expired. After a series of congressional hearings, wherein legislators took the opportunity to air their personal grievances against the network, ABS-CBN’s request for renewal was denied and was forced to cease operations. The last time the station went dark was in 1972, under the dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

Public support for ABS-CBN was strong online, but muted on the streets. “Before the pandemic, government’s moves to shut down the network, which President Duterte had repeatedly threatened to do, faced stiff resistance with huge crowds staging daily rallies at ABS-CBN headquarters in Metro Manila and smaller protests in provincial cities,” said Nonoy Espina, chairman of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP).

He feels that had there not been a pandemic, the resistance would have been much stronger. “The protests fizzled due to fears of infection and the imposition of restrictions on movement and gatherings,” Espina said

As in Nepal, pandemic-linked restrictions have allowed government officials to take control of the news narrative by controlling information. President Duterte himself has stopped giving interviews and press conferences, resorting instead to mostly late-night broadcasts billed as addresses to the nation.

As in Nepal, pandemic-linked restrictions have allowed government officials to take control of the news narrative by controlling information. President Duterte himself has stopped giving interviews and press conferences, resorting instead to mostly late-night broadcasts billed as addresses to the nation.

Espina is critical of the addresses, describing them as staged events distilled of critical voices in the audience. “Most of the talking is done by his spokesman and other subalterns,” he said.

“Before, they would try to spin their narratives. Lately, however, they are picking up their cue from Duterte and have been more brazen in resorting to disinformation.”

Both Bhandari and Espina fear that the new year is unlikely to ease the environment for Asian media.

“It would be tempting to say things are looking up, but the sense is that we may be in for rougher times ahead,” NUJP’s Espina said.

“At the moment it is very difficult to predict where we are moving. As journalists, we have to do our job. Dig in for investigative stories and make the government and our politicians more accountable,” Bhandari said. “The coming times demand us to be more vigilant and accountable.” ●

Amantha Perera has over 15 years of experience as a journalist. His works have appeared in TIME, Reuters, the Guardian, and the Washington Post. He also works as a regional coordinator and trainer for the DART Centre Asia Pacific. He is currently pursuing post-graduate research on online trauma threats faced by journalists and their impact at the Central Queensland University in Melbourne, Australia.