|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

At first glance, it would seem Sarah is doing more than well. A Brazilian citizen, she is earning a respectable sum as an English teacher in China, arguably one of the most fascinating countries in the world. She is also formally learning Mandarin, which will not only make it easier for her to navigate China, but will also enrich her resume.

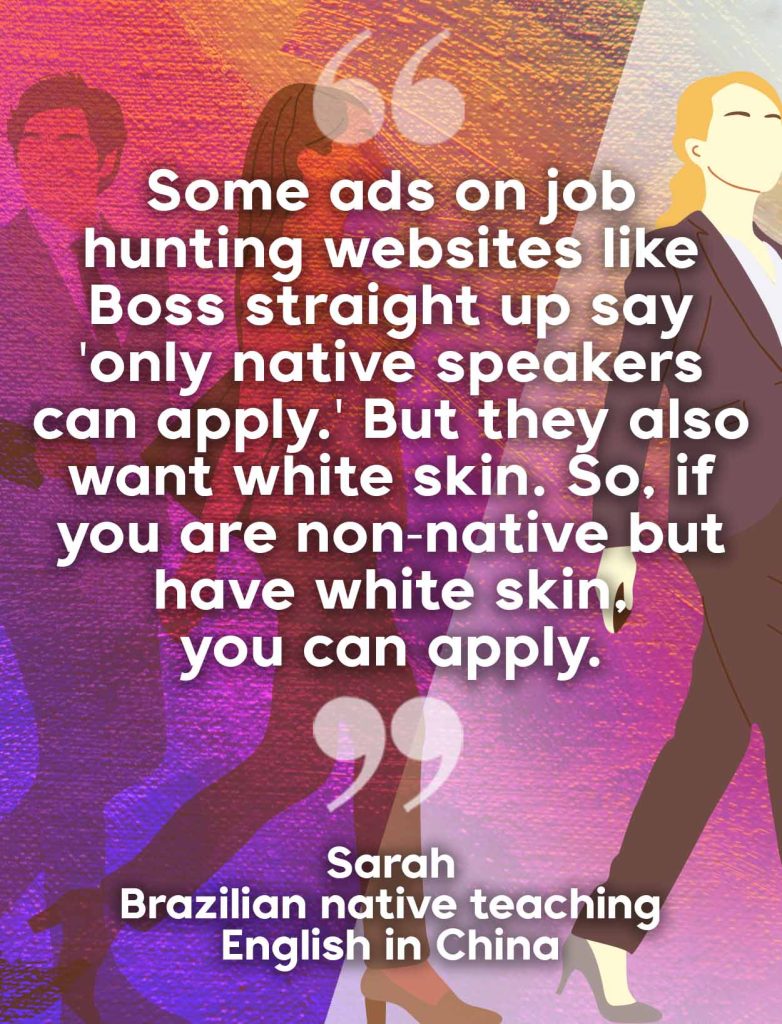

But the 32-year-old – who, like the rest of the interviewees in this article, asked to be referred to via a pseudonym – says that she is not earning as much as some of her colleagues simply because she is not a native English speaker. And if it hadn’t been for her fair skin, she may have also been expected to do tasks that are not assigned to white-skinned, native English speakers.

“Skin color is hugely important here,” says Sarah. “Schools want white teachers. (At application stage) they will outright ask for your nationality and ask you to send your introductory video to see if you look white and Western enough or not.”

“Some ads on job hunting websites like Boss straight up say ‘only native speakers can apply’,” she continues. “But they also want white skin. So, if you are non-native but have white skin, you can apply. There are chances that they would hire you. I get away with more because of how I look.”

For many people in the younger demographic such as Sarah, working in a foreign country is a dream since it combines adventure and income. China is among their favorite target employment destinations, especially for those coming from the West and Latin America. But even those with stellar credentials and skills soon find themselves dealing with discrimination and questionable official policies.

Some expats in China say, however, that such discrimination is more rampant in institutions teaching English. “There is racism in English teaching, but in other sectors there is not much racism,” says George, a foreigner working as a software engineer at a private Chinese company. “The companies look for qualification and expertise, not looks.”

He says that any foreigner who has ability, qualification, and skills could get a job in China. If they know Chinese, he adds, then that would be another point in their favor. “My company often offers trainings in inclusivity, teamwork, and the like to develop a healthy work culture,” says George. “I am sure other companies do the same.”

Western and white

There is no available official data on how many foreigners are currently teaching English in China, although the number is believed to be in the thousands. The National Statistics Bureau of China, however, says that in 2021, the country had nearly 850,000 foreign nationals, including residents of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR), Macao SAR, and Taiwan.

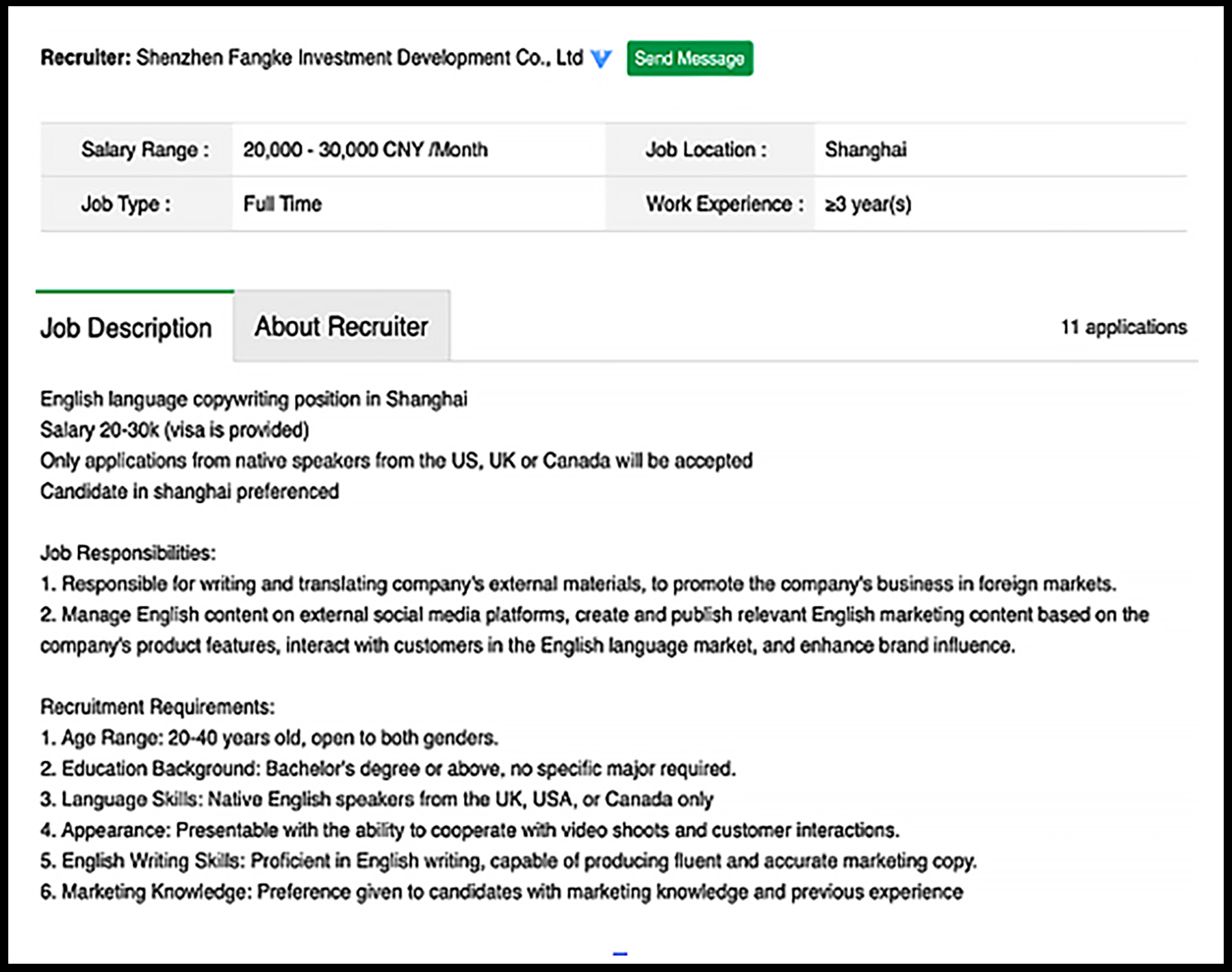

Chinese companies and recruitment agencies deny practicing discrimination based on race or nationality. But their job advertisements often tell a different story. For example, one advertisement published on eChinacities for a copy editor position clearly states that candidates must be native English speakers and “presentable.”

In China’s multibillion-dollar English-language-class industry, physical looks and especially skin color are added, but unspoken, requirements.

Local laws already stipulate that only nationals of the United Kingdom, Ireland, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa who hold a bachelor’s degree in any course and a certificate to teach English as a foreign language are eligible to work as English teachers in China. But many of those hired to teach English say that the preference for a good-looking Western face usually trumps that for good English – and laws.

To save money, many English-language institutions resort to hiring non-eligible native English speakers, as well as non-native English speakers with good accents. What they rarely compromise on is their preference for light skin and Western good looks.

Brazilian teacher Sarah recalls that her recruiters had asked her to tell her students’ parents that she was American. Her current school in Beijing has five foreign teachers, but two of the native English speakers are black. Whenever there is a parent-teacher interaction at the school, Sarah is asked to participate instead of the other non-white teachers.

According to Sarah, the non-native English speakers, especially non-white ones, are also made to do tasks that are not among their job duties, such as taking children to the bathroom and standing at the school gate early in the morning to welcome students.

“Non-natives do all the grunt work — taking children to bathrooms, and staying late,” she says. “Native English speakers just teach and have fun at work. They are paid more than us, almost double. At one kindergarten, native English speakers were paid on the fifth of every month and non-natives were paid on the 15th of every month.”

Chinese job recruiter Paul says that they have to follow the official rules that allow only nationals of seven English-speaking countries with specific qualifications to teach English in the country’s schools. But while he admits that many schools do hire non-native English speakers, he insists that they do so based on the accent, not skin color. “No, it is not about skin color, it is about pronunciation,” Paul says. “Chinese want their children to have an American accent so they prefer American teachers.”

Another recruiter, Kelly, says bluntly that Chinese parents want white teachers. They don’t say it openly, she says, but they want it.

“It is easier for white people to get English teaching jobs in Chinese schools if their accent is good,” says Kelly. “They can pretend to be from a country where English (is the first language). The schools even tell them to do so. They tell them to leave when the police or (a representative of) the education ministry comes for inspection because (under the law) they are not allowed to teach.”

Both the school and the foreign teacher in such a situation are taking serious risks, however. According to Chinese law, those engaged in unauthorized work can be fined up to RMB 5,000 (about US$680) and detained for five to 15 days. In more severe cases, illegal workers may be kept in detention centers before deportation. Schools, recruiters, and hiring managers found to have enabled such illegal employment also pay heavy fines and may have their business licenses revoked.

Not just foreigners

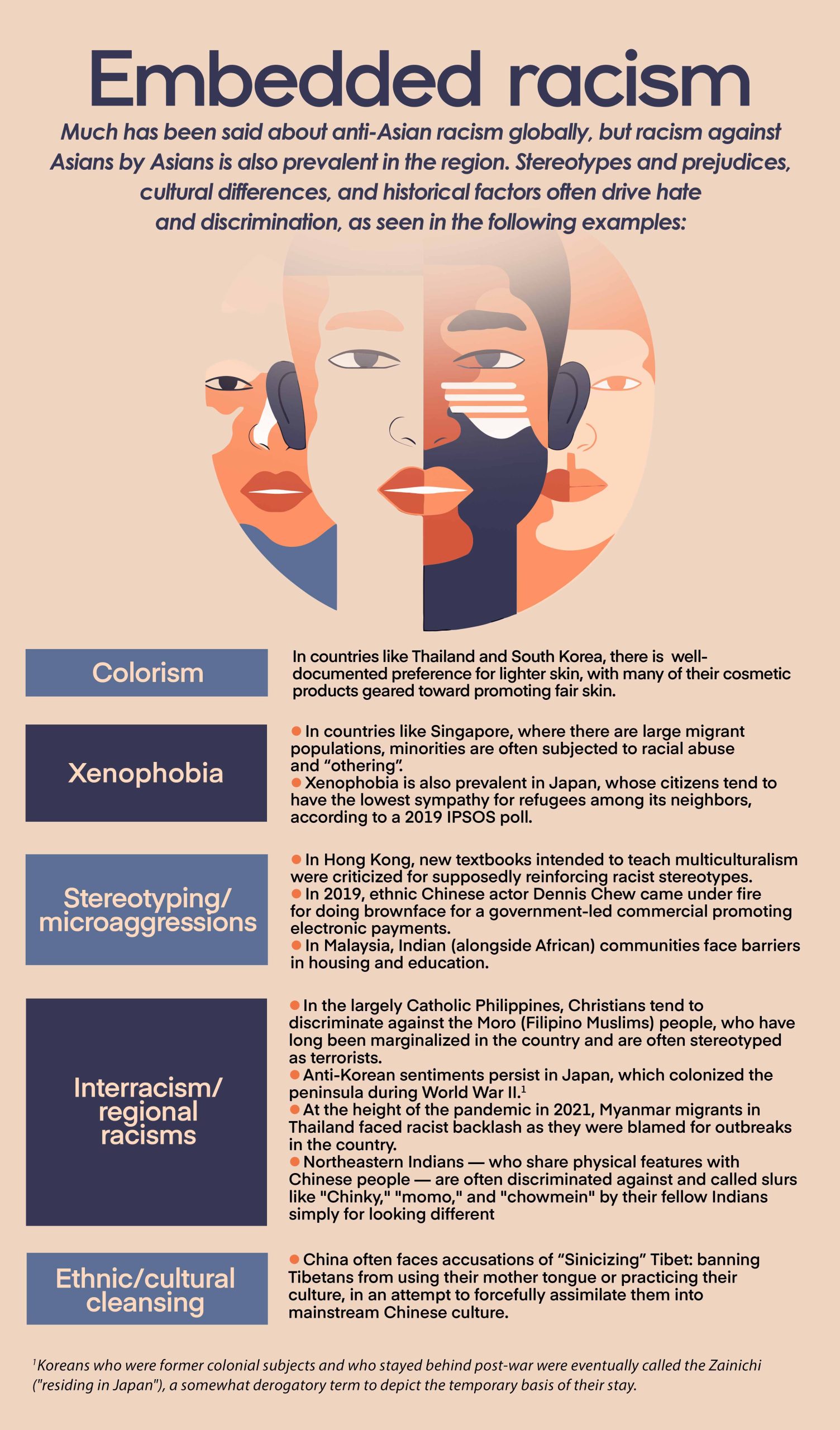

For sure, though, many of the biases against foreign workers seem to reflect ingrained prejudices that exist within Chinese society itself. The language and accent biases, for instance, are felt by Chinese job applicants, with the native Mandarin speakers edging out those with regional dialects. In particular, migrants from Xinjiang region in Northwest China face extreme scrutiny at job interviews.

The job advertisements on Chinese recruitment websites and apps also often say that the candidate should be attractive, young, and fair-skinned. Chinese women have complained as well that during interviewees companies often ask them if they are married or have children, and then decline to hire them if they say yes to either query. Recounts a young, female Chinese architect: “Interviewers often ask women: ‘Are you married? Do you have plans to have a baby within three years?’ I think that’s discrimination.”

John, an Australian teaching economics at a Chinese high school, remarks that racism exists everywhere. But he points out that one could legally challenge discriminatory practices and policies in many other countries, unlike in China.

Previously hired by a Chinese university to teach economics, John saw that contract rescinded even before he stepped foot on Chinese soil. He had asked the university human-resource officer if certain medicines and certain procedures were easily available in China. Initially, John says, the officer had replied to his questions. But when he asked more questions, she told him that the university was terminating his contract due to his health issues. John was left in deep shock.

“They already had my health certificates when they applied for my work visa,” says John, who had undergone heart surgery two years earlier but was more than fit to teach. “They knew about my health condition. It made no sense at that point to terminate my contract. When I asked the reason, they vaguely said that the policies had been updated.”

“At least in Australia I could take legal action if someone exploited my health like this,” he says. “In China, I have little recourse as a foreigner.”

But John says that he still wanted to fulfill his dream of living and working in China due to his lifelong curiosity about the country’s history and development. Too, as a citizen of a Western nation, he knew he could earn a higher salary in China than back home. “That financial incentive made me willing to compromise, even if it meant enduring some discrimination,” he says.

John contacted other recruitment agents in China and managed to secure a contract with a high school there. He flew to China a month later, but he says that the experience taught him a couple of lessons about dealing with mainland Chinese.

One, says John, is to keep your problems to yourself. The other is to refrain from openly challenging the Chinese establishment, he says.

“If you embarrass them by calling out their lies or wrongdoing, you will end up in trouble yourself as a foreigner,” John says. “It is smarter to resolve issues quietly.” ◉