|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

It’s a U.S. app that is accessible in China and is supposed to be for finding dates, but 37-year-old Beijinger Grace uses it for something else. The app’s “BFF” feature in particular is the tech worker’s favorite, using it to discreetly locate other feminists and turn her online matches into online friendships. These lead to offline meetings in cafes, parks, and sometimes her apartment.

Grace and her friends share their ordeals with each other and provide emotional support to one another. While they cannot openly fight the system, they find solace in being there for each other.

“Sometimes I feel lonely because I cannot communicate on feminism and women’s rights with people around me,” says Grace, who wants to be known only by her English name. “My feminist friends give me the emotional support that I need.”

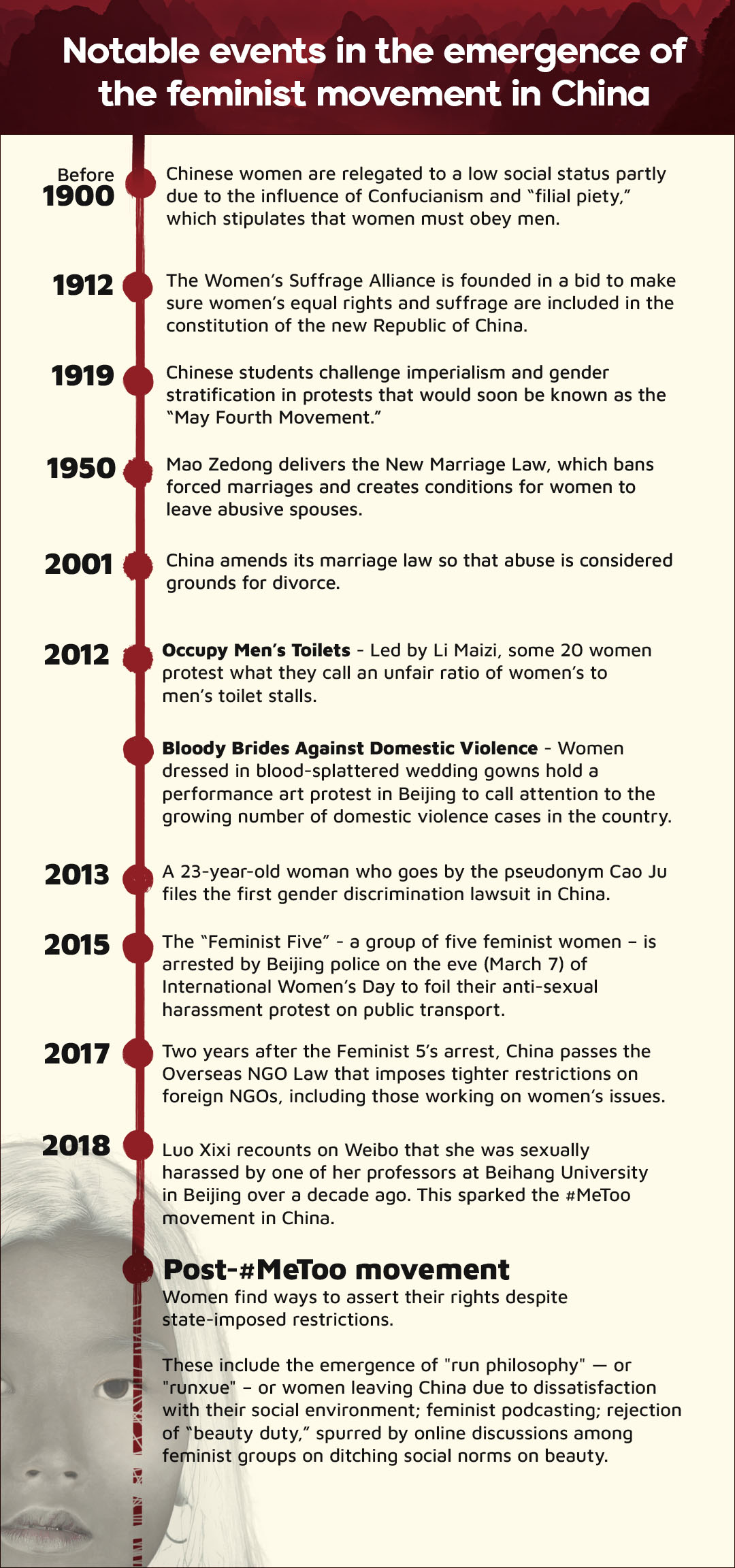

Like other movements, feminism faces severe restrictions in China. The government has cracked down on feminist networks, with the police in the past several years arresting feminists and women’s rights advocates across the country. Social media outfits also censor most discussions on the subject. Platforms within China operate under heavy monitoring, with certain words and phrases — and certainly not only those on women’s rights — automatically blocked by the “Great Firewall.”

But Chinese feminists are using a tactical mix of Chinese and Western online platforms to evade state censorship and keep their conversations going. They have also resorted to coded language, subtle imagery, and cryptic references to talk to each other about women’s issues. When more overt organizing and discourse is required, they turn to Western platforms beyond the firewall’s reach.

Defining ‘feminism’

Indeed, in the age of the internet and fast-changing technology, women in China still have to contend with patriarchal attitudes that hold them hostage in more ways than one. And while feminist viewpoints are taking root among China’s younger urban women, the term “feminism” itself still carries negative connotations.

“Most times I avoid calling myself a feminist to strangers,” Grace admits. “Definitions vary, so people often misunderstand it.”

“Most times I avoid calling myself a feminist to strangers,” Grace admits. “Definitions vary, so people often misunderstand it.”

But she adds, “It is not limited to China. Everywhere, people have a negative image of feminism and feminists. Once in the United Kingdom, a Japanese woman asked me if I hated men. I explained my views – that feminism isn’t about hating men.”

“For me, feminism means standing up for gender equality and women’s rights, but not through hating or attacking men,” Grace explains. “Chinese society has misconstrued what it means to be feminist in China. It is not easy to openly call one’s self feminist here. That is why we find subtle ways to connect and empower each other discreetly.”

In most cases, that meant going online. While it remains difficult for Chinese feminists to organize in the form of traditional groups, they are able to use online platforms like the video-sharing platform Bilibili and the Chinese version of Instagram, Xiaohongshu, which is commonly known as “Little Red Book,” to discuss women’s concerns and rights.

According to Professor Zheng Rui of the Communication University of China in Beijing, feminism is more openly discussed online in China than offline due to the anonymous nature of online platforms.

“The topic is still taboo in the real world,” she explains. “This is likely due to negative connotations attached to the term ‘feminism.’ But in practice, women enjoy equal rights with men in many respects.”

She also says that while feminist discourse is rising online, it reflects greater awareness, not outright activism. Notes Zheng: “Feminism in China is about informing women of their rights, not organizing collective action. It communicates to girls and women that they can enter diverse fields and occupations. The message is that they deserve these opportunities — these are their rights.”

Grace meanwhile points out that the term “feminism” carries connotations that clash with China’s patriarchal social norms. This is, after all, a country where practices like foot binding that restricted women’s mobility, arranged marriages focused on reproduction, and widespread gender discrimination both at home and in society used to be common. For centuries, women were largely confined to domestic servitude and lacking extensive rights.

After the Communist revolution in 1949, laws banning arranged marriages and granting women equal rights in areas like employment, property ownership, and divorce were enacted. Since then, the situation has changed substantially for women. Professor Zheng says that gender equality has become an official priority of the Chinese government, invoking the late Chairman Mao Zedong’s famous proclamation that “women hold up half the sky.”

But many other women such as Grace believe women are still getting the short end of the stick and that there is still great progress to be made toward full equality.

Making cyber connections

Grace’s own journey into feminism began through the podcast of Linwen Qin, a Chinese feminist residing in Germany. This podcast is no longer accessible in China. The ban on her favorite podcast and other feminist voices prompted Grace to seek connections with other like-minded women. She began following outspoken voices on Bilibili and Weibo, another popular China social media platform, to expand her network.

Many of the influential bloggers on these platforms run WeChat groups for their communities. Grace initially joined some of those groups to observe the discussions. Feeling drowned out by the large crowds in these public groups, however, she soon left in search of more personal interactions within a close-knit community.

“In those groups, people would try to persuade others to agree on their ideas,” says Grace. “I believe we should discuss ideas, not persuade each other. I prefer meeting local women in person. It allows more authentic discussions.”

Like Grace, Mei keeps her feminism-related discussion to a close group of her female friends. According to the 19-year-old who also wants to be referred to by her first name only: “It’s not easy to build a feminist community here. We lack a concept of activism groups. With limited organized mobilization, we rely on media to communicate, though we cannot gather in person often.”

Mei follows several bloggers on Bilibili and Xiaohongshu who highlight challenges faced by girls and women. One of her favorite Bilibili bloggers is a mother who raises awareness about issues affecting pregnant women. Another blogger she admires creates content on Little Red Book that analyzes how changing beauty trends in China affect women’s physical and mental health.

But Mei is cautious about the motives of some bloggers who, she says, might use feminism for financial gain.

“On Chinese internet platforms, many bloggers use feminism to make money,” the teenager says. “I do not fully agree with their views. I have unfollowed them. I am instead spending my time reading books on feminism to have a better understanding of it.”

Generational and gender gaps

Professor Zheng observes that the divide between online and offline discourse also reveals generational gaps in comfort levels. While young women actively engage in feminist debates online, she says, older generations remain wary of destabilizing gender norms. The nature of online platforms also allows the users to talk about this “taboo” subject of the real world.

“The online discussions on feminism fall under group communication — those tend to be more emotional and less rational,” continues Zheng. “In real life, people do not talk openly about feminism.”

She also points out how the heated online debates on feminism have been creating divisions between genders. Says Zheng: “On social media, clashing opinions on feminism arise. Some talk in its favor and some reject the idea entirely. This causes confusion between genders. Men need to understand women just want to protect their rights in this male-dominated society.”

Some of these discussions and debates, however, are starting to trickle offline. Zheng says that even mainstream media outlets in China have developed a growing interest in feminist themes, sparking discussions on gender issues through popular culture.

“There is an ongoing TV drama called ‘不完美的受害者 (Imperfect Victim)’,” she says. “It is not very famous but it has stirred an important discussion in China. It is about a girl who was assaulted by her boss. There is a heated discussion going on about the drama, questioning who is really the victim — the girl or her boss.”

For now, however, the women and girls who identify themselves as “feminists” are walking a fine line — progressive in their thinking, yet cautious in how public they can be. But that hasn’t stopped many of them from trying to connect with each other.

Wang Ziye, who embraces the “feminist” label heartily despite its lingering negative image in China, says she uses Weibo to find like-minded friends.

“I prefer to make friends with those who share my feminist perspective,” the 25-year-old Shanghai university student says. “Having the same values is a core factor for me when choosing friends. I reach out to those girls/women who show feminist tendencies. I follow them and if they respond to my request I try to befriend them, too.

“I also communicate with other users in the comment area,” says Wang. “I love the feeling of being in a feminist community, whether it’s online or offline.”◉

Tehreem Azeem is a freelance journalist based in Beijing. She reports on gender, culture, and violence. She is doing PhD at the Communication University of China and tweets @tehreemazeem.