|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

T

he new Hollywood blockbuster “Oppenheimer” has been gathering critical acclaim since it opened recently, but one “flaw” that some moviegoers say it has is that it never shows the human tragedy wrought by the nuclear bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Masahi Ieshima, however, is among those who need not see such footage. When U.S. forces dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, he was living there with his family. Only three years old at the time, Ieshima vaguely recalls being strapped on his mother’s back and escaping the toxic cloud of radiation as a fire ravaged their house. Three days later, the U.S. military dropped a stronger, plutonium-core bomb on Nagasaki, more than 400 kms southwest of Hiroshima.

Officially, Hiroshima lost 140,000 lives in 1945, and Nagasaki 74,000, because of these bombings. Thousands more died years later due to illnesses related to the radiation or to injuries sustained during the attacks. Ieshima’s father, who was at his office that was within the explosion’s three-km epicenter range, died of jaw cancer decades after, at the age of 57.

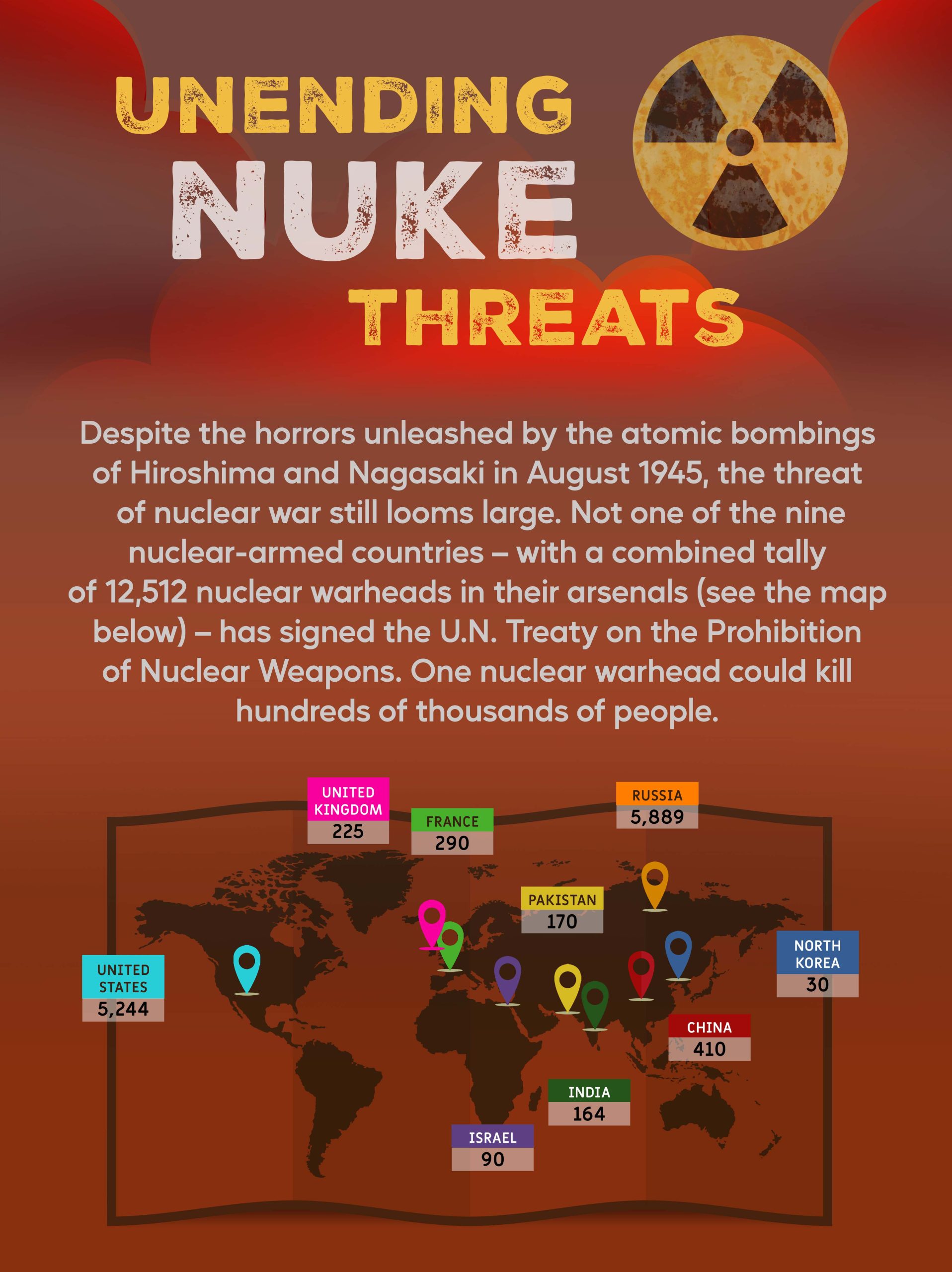

To this day, debate continues to rage over the decision of the United States to put an end to World War II by dropping the bombs. Although Japan did surrender days after the Nagasaki bombing, political and security experts say that the attacks triggered the nuclear arms race and that the threat of a nuclear war has since hung over the entire world.

The irony is that Japan – which is the only country to have experienced firsthand the horrors wrought by nuclear bombs – has not signed any of the international treaties aimed at preventing the proliferation and use of nuclear weapons. And with the number of hibakusha – Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors – fast dwindling year after year, Japanese anti-nuclear activists say that they are losing some of the world’s strongest peace advocates.

A major concern in largely pacifist Japan is Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s push for the country to actively support the U.S. military against the backdrop of Russia’s attack on Ukraine and North Korea’s continuing launch of missiles. Just last January, Kishida and U.S. President Joe Biden signed a joint statement on the Japan-U.S. alliance that among other things contained Washington’s promise to defend Japan “using all capabilities, including nuclear weapons.”

The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) has also noted Japan’s unwillingness to sign or ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). In fact, it says, “Japan has consistently voted against an annual U.N. General Assembly since 2018 that welcomes the adoption of the TPNW and calls upon all states to sign, ratify, or accede to it ‘at the earliest possible date’.”

Armed with eyewitness accounts

For anti-nuclear activists and the hibakusha themselves, the survivors’ eyewitness accounts are the strongest weapons they have against nuclear armament. Through the decades, the hibakusha have released tens of thousands of anti-nuclear arms messages and spoken of their physical and mental suffering at countless peace conferences, and at schools and in the United Nations.

According to the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare, however, old age and illness are fast depleting the country’s A-bomb survivor population. In 1981, there were 372,264 certified survivors on the official list. By 2022, the figure was down to 118,935; data from the ministry also indicated that the hibakusha’s average age then was already 84.53 years.

Now 81 years old and retired, Ieshima says, “As we age, the biggest tragedy is that we feel no respite from the pain we have endured. We are gripped with hopelessness because world leaders have not accepted the reality of human suffering caused by nuclear weapons.”

Last 23 July, survivors in Tokyo, braving the searing summer heat, held an advanced 78th commemoration of the twin bombings. Ieshima, representing the bereaved, reported 249 deaths in the city, leaving the hibakusha at the national capital at 3,838. This 6 August, Hiroshima will lay to rest 289 survivors.

Professor Robert Jacobs, nuclear historian at the Hiroshima Peace University, says that a world free of nuclear weapons represents the core of the hibakusha movement, which equates this goal as critical in easing the survivors’ past suffering.

“As survivors of one of the world`s most horrifying attacks on humanity, they have endured debilitating physical and mental injury for decades,” Jacobs says. “With age their anxiety grows as they realize their suffering may never be addressed and could be in vain.”

Last May, many hibakusha were disappointed yet again over the outcome of the Group of Seven Summit hosted by Prime Minister Kishida in no less than Hiroshima. The Japanese leader, who represents the Hiroshima constituency, had been quoted as saying that the city was chosen as the site of the summit because “conveying the reality of the nuclear attack is important as a starting point for all nuclear disarmament efforts.”

But hibakusha later noted that while the G-7 official statement “underscored the importance of the 77-year record of non-use of nuclear weapons and reconfirmed the commitment to achieve a world without nuclear weapons,” it stopped short of outlining steps toward this vision.

In an interview, Ieshima called the high-profile meeting “devastating.” Setsuko Thurlow, 91, the first survivor to speak at the Nobel Peace Ceremony, told the Japanese press that the summit was a “failure” because it had failed to discuss the abolition of nuclear weapons. (Thurlow accepted the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017 on behalf of ICAN.)

Tales needing to be heard

As it is, hibakusha already “feel forgotten in Japan’s postwar materialistic society that has little time for them,” says Yuji Sawai, a medical counselor working with aging survivors in Tokyo.

University student Misamoto Kaji told the Japanese broadcast network NHK that when she was at the Nagasaki city center last year, she was “shocked” to see “how few people were actually paying their respects,” with most failing to stop and reflect when a siren sounded at exactly 11:02 a.m., marking yet another anniversary of Nagasaki’s bombing.

Still, there are many people and organizations who have now turned their attention to making sure the voices of the hibakusha are heard even long after they are gone. Last December, Kaji and other university students held a virtual conference for high schoolers, during which they narrated the stories told to them by Nagasaki hibakusha.

In Hiroshima, the city government has expanded a program aimed at passing on the survivors’ stories. Under the original program called ‘A-Bomb Legacy Successors,’ volunteers spend time with the survivors and learn about the latter’s wartime experiences. The volunteers, called ‘memory keepers’, then share these with the public through talks and special events. Last year, the city government decided to recruit the relatives of the survivors to tell their tales.

According to the online Hiroshima Peace Media, the older version of the program had been able to attract 149 memory keepers who passed on the stories of the hibakusha to visitors at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and to schoolchildren. Their trainers included some hibakusha themselves.

Associate Professor Chie Shijo of the Hiroshima Peace Institute says that many hibakusha waited four decades before they told their stories due to strong discrimination toward the bomb survivors after the war. One cause of this was the belief that radiation could be contagious.

Shijo says that her current research focuses on “discovering the voices of the hibakusha who have passed away without talking about their experience.”

“Many of them were social outcasts such as prostitutes or the disabled,” she says, adding that Roman Catholic hibakusha were also among those who experienced discrimination. She says that she is gathering their voices through their diaries and other documents, as well as speaking with their relatives. Shijo says this process will become a path to revisit the deeper issues of war.

Speaking to the press this July, Hiroshima Mayor Kazumi Matsumi pledged to use the city’s wartime experience into making it a leading international center responsible for promoting the culture of peace.

“Hiroshima will support the development of developing a grassroots movement across countries that promotes the education of people to act for peace,” he said.

Shijo herself believes that there will eventually be an expanded peace movement in Hiroshima. She says that this may even include the global survivors linked to atomic testing elsewhere, such as those conducted by the United States in the Marshall Islands between 1946 and 1958.

In all probability, those who pushed on with those tests had missed reading U.S. writer John Hersey’s account that focused on six Hiroshima survivors. Published in August 1946 by the New Yorker magazine, the piece followed the six survivors from the time the bomb dropped to a year later, when they were still not what they used to be – and perhaps never would be again. Included in the long article was a reflection by one of them, a Jesuit priest who had been reading a magazine when the bomb fell on the city.

In a report to the Holy See, the priest wrote in part: “It seems logical that he who supports total war in principle cannot complain of a war against civilians. The crux of the matter is whether total war in its present form is justifiable, even when it serves a just purpose. Does it not have material and spiritual evil as its consequences which far exceed whatever good might result? When will our moralists give us a clear answer to this question?”◉