|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

(First of two parts)

I

In 2022, Jessica* tried to apply for a local job and went to a police station to request a clearance certifying she has no criminal record. But she was arrested and thrown in jail right then and there.

She had no idea she was facing charges over a loan she had taken out over a decade ago, and that a warrant had been issued for her arrest.

“I cried and cried. It was my first time to be jailed,” she told the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ). She was released after posting bail.

In 2010, she took out a PhpP80,000 (US$1,465.84) loan from money lender Nittan Capital Finance, Inc. (NCFI), a company referred to her by the recruitment agency when she applied for work as a domestic helper in Hong Kong. She needed the money to pay for the job requirements.

Hong Kong didn’t work out. She was terminated after 10 days. There was no explanation,” she told the PCIJ.

She later found another job in Taiwan and worked there as a domestic helper for two years, which helped her pay off the bulk of her Hong Kong loan.

Initially, she managed to pay Php60,000 (US$1,099.38) or 75 percent of the entire loan before interest. Then, she stopped paying and then totally forgot about it — until that day she was arrested.

Jessica’s story is a cautionary tale for Filipino overseas workers, who are forced into debt even before they leave the country.

It’s a problem crying for a comprehensive government solution. It demands the attention of the year-old administration of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., according to migrant workers’ groups, who are banking on his promise to protect migrant workers.

“Workers should not be required to take on debt to secure their job placement, as these fees are the responsibility of the employer, who should cover these costs,” said Migrasia, a Hong Kong-based non-governmental organization which has helped migrant workers file complaints and seek legal recourse against possible exploitation.

Forced to issue post-dated checks

Failure to pay a debt is not a crime. But, like Jessica, one can land in jail for issuing post-dated checks.

Jessica had a standing arrest warrant for five counts of alleged violation of the Batas Pambansa Blg. 22 (B.P. 22), or the Anti-Bouncing Checks Law. She said she was not aware of the charges and did not receive court summons. The law, enacted in 1979, penalizes anyone who issues a check knowing that the bank account has insufficient funds to cover the amount.

Some workers sign blank checks without reading them, while others are coerced by their recruiters and lenders into doing so, according to migrant workers’ groups.

Some workers sign blank checks without reading them, while others are coerced by their recruiters and lenders into doing so, according to migrant workers’ groups.

Forcing workers to issue post-dated checks for loan payments, “either personally or through a guarantor or accommodation party,” is prohibited under Republic Act 10022, which amended the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act.

But the recruiters and some lenders know the law more than the workers, and have used it to their advantage.

So when the workers fail to meet monthly payments, they are brought to court for violation of B.P. 22. Even their family members, who are their co-borrowers, are also charged in court.

“It definitely is a tool that is very intimidating for migrant workers. Would agencies and lenders find some other way to intimidate clients if they couldn’t use B.P. 22? Probably,’’ Migrasia told PCIJ.

“But it’s an effective tool that benefits lenders and agencies, who are well resourced and understand the legal system better than the migrant workers they are intimidating,” it added.

In her case, Jessica said she didn’t know Nittan Capital filed a case against her in court. She missed notices of court hearings and skipped them, leading the court to issue a warrant for her arrest.

Nittan is a subsidiary of Nittan Capital Holding Company Limited Hong Kong. The Hong Kong-based firm is part of a group operated by Central Tanshi Company Limited, a financing company in Japan.

The PCIJ reached out to Nittan Capital, but the money lending company refused to be interviewed. Apart from Jessica, the PCIJ confirmed at least three other overseas Filipino workers (widely referred to as OFWs in the Philippines) who faced B.P. 22 charges filed by Nittan.

Predatory lending and labor abuse

A comprehensive government solution is needed to address why Filipino overseas workers are forced into debt in the first place.

A placement fee equivalent to a month’s worth of salary may be charged against an OFW. But in 2006, the Philippine Overseas Employment Agency (POEA) resolved to make an exception for domestic workers “in recognition of the nature of their work and their vulnerability to exploitation and abuses.”

POEA is a government agency that monitors and regulates overseas employment of Filipinos. It has now been absorbed by the new Department of Migrant Workers (DMW).

There are recruiters, however, that circumvent POEA policy by lumping the placement fee with payments for training center and medical clinics, according to Ellene Sana, executive director of the Center for Migrant Advocacy (CMA), a local nonprofit promoting the welfare of OFWs and their families.

The acceptable training fee is around Php11,000 (US$201.784), but many OFWs are being charged between Php80,000 US($1,467.52) and P90,000 ($1,650.96), she said.

“It’s very common for overseas Filipino workers to think that training is required because that’s what they’re told in the Philippines. It’s important to know that payment for training is where the majority of debt comes from, so overseas Filipino workers should know whether it’s actually required in the first place,’’ Migrasia said.

“For example, if migrant domestic workers are required to take training, their employer or agency is supposed to pay for it, which rarely happens. It’s frustrating that so much of the debt originates from a service that often isn’t required, and is something Filipino migrant workers aren’t supposed to be paying for,” it added.

Two in five OFWs reported “either feeling that they had no choice at all or were pressured” to use a medical clinic, training center, or lending firm, according to Migrasia data.

“Overseas Filipino workers go abroad wanting the best for their families, and often are willing to do whatever it takes to care for them. The agencies who are supposed to help them take advantage of that, and make them pay,” Migrasia said.

In many cases, the workers are aware of the agency’s illegal requirements, but still go ahead because they believe “there’s no other way for them to migrate,’’ it added.

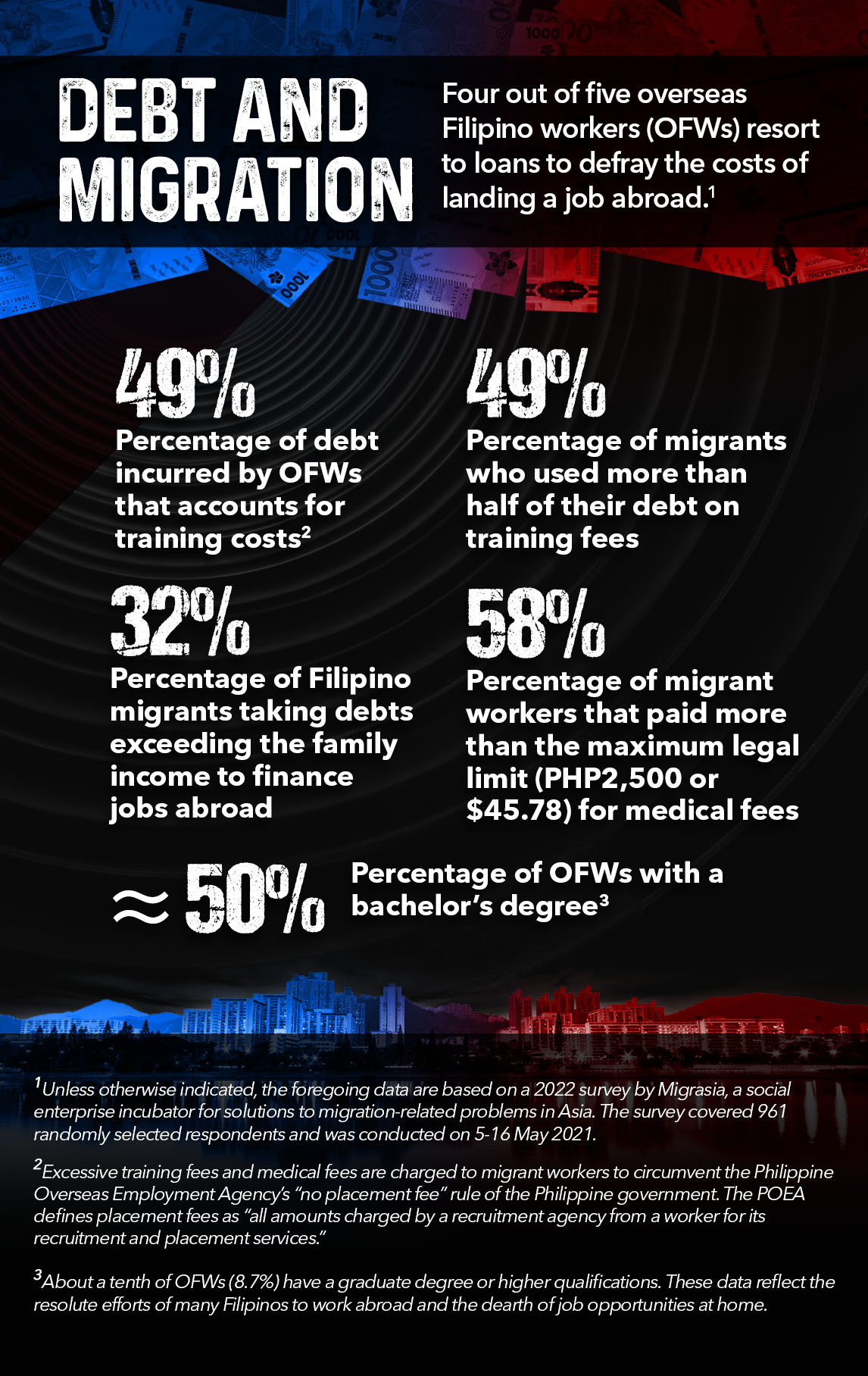

A 2022 Migrasia study showed that four out of every five surveyed verseas Filipino workers, or 80.5 percent, went into debt to finance their job placement abroad.

“Although the recruitment fees or placement fees specifically were banned in 2006, there was really a shift in fees from agencies to other migration intermediaries like training centers. Migrant workers are required by the agencies to go to specific training centers and medical clinics, who charge fees that far exceed what those services should cost, and which are often unnecessary in the first place,” Migrasia said.

“Even though the Philippine government outlawed most recruitment fees many years ago, overseas Filipino workers are being required to pay to migrate. To finance these illegal fees they are referred to money lenders who grant excessive interest loans. When they are unable to repay these loans, workers and their families face all forms of harassment from both Philippines and Hong Kong money lenders, and collection agencies. In the most egregious cases on the Philippines side, we’ll see migrant workers that are directed by the agency and money lender to a bank, required to open a bank account and sign a number of blank checks, which will be held over their head as a threat — to be cashed with the intention of triggering a B.P. 22 violation — if they’re unable to pay back an installment of their loan.”

The same study stated that a third of them “took on debt that was larger than their annual household income.”

A substantial part of this debt, it read, went to training and medical examination fees. Training fees contributed to more than half of the debt incurred by offshore Filipino workers, according to the study.

OFWs surveyed by Migrasia also reported being “required” by recruiters to get services from preferred facilities. Their study found that 44 percent of Filipino migrant workers reported being mandated to use a specific training center, while 53 percent reported the same for the medical clinic.

The imposition of “a compulsory and exclusive arrangement” requiring OFWs to avail themselves of a loan, undergo health examinations, and join training is prohibited under the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) rules.

Even so, the prevailing overseas employment system traps OFWs in debt before they even depart for their work abroad.

Familiar scene

Jessica was released from jail after her husband posted Php12,500 bail (US$229.3), an amount that her family borrowed and that exceeded her gross monthly income.

She’s now forced to make monthly payments or risk future jail time.

Her case is pending in court. For the arraignment in May, Jessica had to travel more than 22 hours by sea from Leyte, a province about 1,000 kilometers south of the Philippine capital. She had to borrow money for her fare.

Lugging one suitcase, one duffel bag, and a backpack, Jessica was in tears as she walked along the hallways of the court in Pasig City. The rain did not let up that afternoon, as if to sympathize with the 41-year-old mother of five.

She knew no one in the city. She came without any means of going back home.

This has been a familiar scene in courts.◉

*Not her real name

This story was originally published by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ). It was produced as part of the Trafficking Inc. investigation by journalists from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, The Washington Post, NBC, WGBH Boston, Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, PCIJ, and the Investigative Reporting Program at the University of California, Berkeley.