|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Gulshan* says that it was her husband who had taken to heroin first. But he had been instrumental in getting her started on the drug six years ago, ironically in an attempt to help her.

“I was pregnant at the time and we didn’t have any money to buy medication,” recounts the now 26-year-old mother of four. “My husband asked me to take a hit of heroin to ease the pain. I have been using heroin ever since.”

Indeed, experts reveal that a significant number of Afghan female addicts are initiated into drug use by their husbands or male relatives. Yet the increasingly female face of what has been called one of Afghanistan’s ‘silent tragedies’ has often been ignored.

The U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates that Afghanistan has at least 3.5 million drug addicts, or nearly 10 percent of its population. Previously concentrated among men who had worked as laborers or had been war refugees in Iran for extended periods, drug addiction in Afghanistan has escalated into a pervasive issue that now spans across the entire nation, and includes an ever-growing number of women among drug users.

In 2009, around three percent of Afghan women were addicted to drugs, although the United Nations believed this number was relatively low because of inaccurate reporting and the stigma of addiction. Yet by 2015, that figure had jumped to 9.5 percent. Five years later, an Afghan government spokesperson was reported to have cited the same 2015 figure; he put country’s number of female addicts at 850,000, although this apparently excluded female drug users under 18 years old.

In any case, the rise in female drug users in Afghanistan has helped lead to daily routines crumbling as traditional Muslim norms, which dictate women’s roles as modest and devoted wives and mothers, are disrupted by the frantic pursuit of drugs.

Gulshan, for instance, admits that she and her husband have kept their drug habit even as their family in the northwestern province of Heart struggles to survive on a meager income. Gulshan confesses that she frequently finds herself making sacrifices on food in order to support her addiction as well as that of her husband.

“My husband is a bus driver and earns AFN 2,000 (US$23) per month as a bus driver,” she says. “We spend AFN 150 (US$1.76) per day to pay for heroin. We are barely left with enough money to feed our children. When they ask for food, I beg outside the mosque or ask help from the neighbors.”

A family affair

Citing a 2015 drug-use survey in Afghanistan, a 2020 study by U.S.-based academics said that the three most common drugs among female addicts are opioids, sedatives, and cannabis. The study also said, “Ingesting drugs is the most common (69 percent) way women report using a drug as it is more socially acceptable than other routes of administration and implies the drug use is for medical purposes.”

It noted as well that “among women who use opium, 78 percent have given opium to their child and/or another family member.” Indeed, it has been suggested that Afghan parents in remote areas of the country resort to giving their children opium as a painkiller or sedative.

UNODC meanwhile said in a 2015 report: “Many children become dependent on drugs, mainly opiates, at an alarmingly young age while in the care of drug-dependent parents or family members.” At that time, the UN agency reported that 9.2 percent of children aged up to 14 years in Afghanistan tested positive for one or more types of drugs and were likely using drugs actively.

According to a March 2023 policy brief on drug use and treatment in Afghanistan, “poorly ventilated homes” may also have contributed to the rise in drug-addicted minors, some of whom may have been inhaling secondhand smoke from the heroin cigarettes of relatives.

Herat resident Saima*, for example, says that she used to complain incessantly about her father’s heroin cigarettes because they filled the family home with smoke.

“There was always smoke in my house,” says the 19-year-old. “I would often argue with my parents because it made the house feel bad. But one day my father asked me to try it too and see the benefits myself.”

Instead of “seeing benefits,” though, Saima recalls feeling sick. She recounts, “My head started spinning and I vomited a lot after I smoked heroin cigarettes.”

That was three years ago. Out of their four-member household, three are now addicts — including Saima.

“The environment of our house is really bad,” she says. “On days we don’t have enough for all of us, we beat each other, throw things, and lie around the house in pain.”

An addictive way to ‘escape’

Laila Haidari, an expert in drug de-addiction and an activist from Afghanistan, says that there are several factors contributing to the prevalence of drug abuse in the country. One is the lack of awareness among families about the detrimental effects of addiction. The pressure of striving to earn a sufficient income also plays a role.

For sure, long-standing poverty and the devastating impact of decades of war are among the major reasons fueling Afghanistan’s drug problem. The situation has even worsened significantly following the collapse of the country’s economy after the Taliban took control in August 2021 and international financing was halted.

Families that used to be able to sustain themselves with various sources of income have now been cut off, struggling to afford even the most basic needs. According to a recent World Bank report, eight out of 10 households in Afghanistan today face food insecurity. It also said that as of April 2023, 36 percent of Afghan households were resorting extreme coping strategies to meet their immediate food needs, such as compromising the quality of what they ate, borrowing money, or reducing the number of meals per day.

“We barely have enough to eat,” Saima says. “We eat dry bread with tea which is also hard to find sometimes because we don’t have money to pay for our food.”

“We barely have enough to eat,” Saima says. “We eat dry bread with tea which is also hard to find sometimes because we don’t have money to pay for our food.”

Unsurprisingly, millions of Afghans have been feeling desperate and especially vulnerable, which in turn has more and more of them resorting to drugs as a temporary escape or coping mechanism.

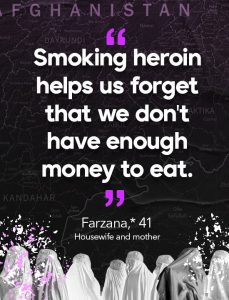

Farzana*, 41, says as much. She works as a cleaner at people’s homes for AFN 200 per day (US$2.35), while her husband is a cart puller at the border of Islam Qala with Iran. But he is usually hardpressed in finding someone needing his services.

“My children have to beg to make money,” says Farzana. “My husband barely finds work and when he does, he only makes AFN100 to AFN 150 (US$1.18 to US$1.75) per day. Smoking heroin helps us forget that we don’t have enough money to eat.”

Long road to de-addiction

“The number of addicts was high, which was left to us by the previous regime,” says Dr. Sharafat Zaman, spokesperson for Ministry of Public Health. “The previous regime could not treat addiction despite immense international aid and support.”

He asserts that the “IEA (Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan) has taken addiction treatment seriously, but needs support and sponsors to provide adequate treatment to the addicts.”

Zaman adds that “considering the need and the scale of the issue, the treatment options are inadequate and really needs to be scaled up.”

Some observers, though, say that the plight of Afghanistan’s drug addicts had been overlooked as the country’s authorities concentrated on putting a ban on opium production and the harvest of wild ephedra, which is used in the manufacture of methamphetamines.

The Taliban’s April 2022 ban on growing the opium poppy in particular garnered worldwide interest. It has since been declared a “success” by some experts, including independent researcher David Mansfield.

Just this June, UNODC released its annual World Drug Report that also noted, among other things, that the “2023 opium harvest in Afghanistan may see a drastic drop following the national drug ban.”

The observation came with caveats, however. Said UNODC: “The benefits of a possible significant reduction in illicit opium cultivation in Afghanistan in 2023 would be global, but it will be at the expense of many farmers in the country who do not have alternative means of income generation. Afghanistan is also a major producer of methamphetamines in the region, and the drop in opiate cultivation could drive a shift toward synthetic drug manufacture, where different actors will benefit.”

Anubha Sood, a senior official at UNODC, also says that they had been surprised by the ban and had heard about it just like everyone else – via social media.

“There was no preparation before announcing the opium ban,” says Sood. “For this ban to be effective in helping drug addicts, it has to have a holistic approach such as providing effective treatment, counseling, follow-up service to the drug user population, et cetera. It is not something that goes away in a month. Announcing a ban will not be enough.”

As it is, Saima feels there is insufficient governmental support to help her stop overcome her addiction.

“I think a lot about quitting, but I am unable because there is no way to do it,” she says. “I have heard from many people that there are a lot of difficulties in the [government-run] centers. They just put you in like a prisoner for six months. Once you leave, you start again.”

In truth, Saima’s gender can itself be an obstacle to her seeking treatment. The March 2023 policy brief published by the pointed out that “women who use drugs are understood to face stigmatization and encounter difficulties in accessing treatment” because of several factors that include “patrilineal family structures, constitutional and legal inequalities, and females as bearers of family honor.”

Haidari, for her part, remarks that banning opium will only solve the problem of drug trafficking. Addiction, however, is a social problem.

“People need to be satisfied with their lives and be happy,” she says. “A bad feeling or hardships can increase their desire to use drugs.” ◉

Names marked with * have been changed.

This story was supported by the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia Journalism School.