|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Y

et another new chapter in Canada’s Temporary Foreign Workers Program (TFWP) began this January as the country rolled out a new scheme that will allow spouses and working-age children of temporary foreign workers (TFWs) to take on jobs.

Announcing the move last December, Canadian Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Minister Sean Fraser said that it was aimed at “helping employers overcome labor shortages while also supporting the well-being of workers and uniting their families.”

But while many foreign migrant workers are welcoming the new move, rights activists and several of the workers themselves say that the Canadian government should address problems plaguing the TFWP first.

For one, many TFWs have had to put up with unsafe and unsanitary working conditions, aside from enduring lower than average pay — if they get paid at all. For another, the program seems to have been hijacked by unscrupulous employers and employment agents, the former practically blackmailing workers so that they would be able to stay in Canada and perhaps qualify for permanent residency, and the latter charging exorbitant fees for their supposed services.

Syed Hussan, executive director of the advocacy group Migrant Workers Alliance for Change (MWAC), says flatly, “Canada uses them (migrant workers) for their labor and then chews them up and spits them out.

Syed Hussan, executive director of the advocacy group Migrant Workers Alliance for Change (MWAC), says flatly, “Canada uses them (migrant workers) for their labor and then chews them up and spits them out.

“This is a human rights catastrophe,” he says. “They [the Canadian government] work hand in glove with sending countries, like the Philippines, countries in the Caribbean and Indonesia, who have effectively created a labor export policy where they export human beings here as workers, and Canada rotates them as workers.”

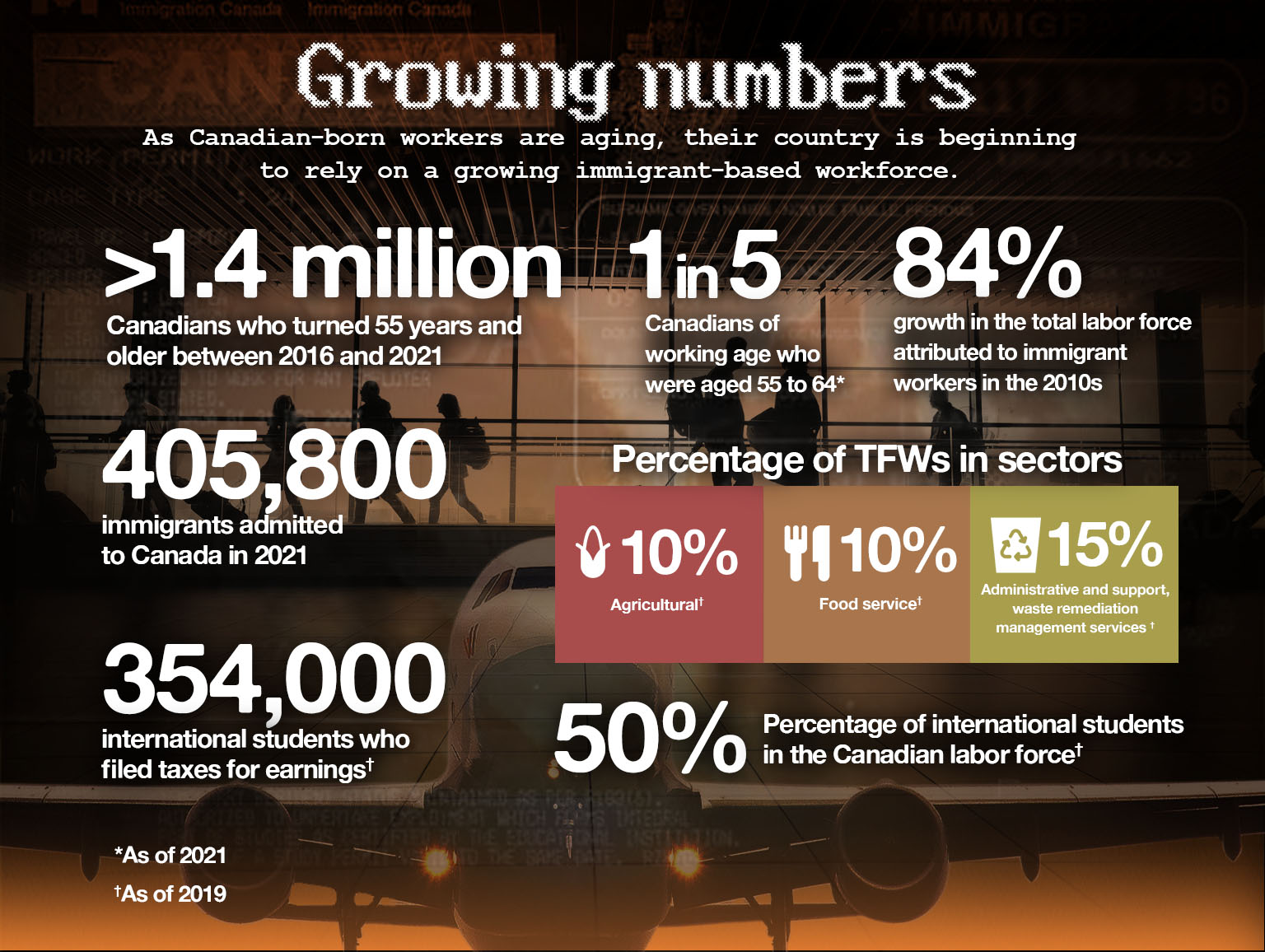

Canada has been having a labor crisis for years. With a rapidly aging population and a declining birth rate, the country has had to rely increasingly on workers from overseas to fulfill its labor needs. The national agency Statistics Canada says that the number of TFWs increased “seven-fold” between 2001 and 2021, or from 111,000 to 777,000.

Increasing numbers from Asia

Latin American and Caribbean countries still make a significant part of Canada’s temporary agricultural workers. But indications are more TFWs in general are now coming from Asia.

According to Statista, five of the 10 top origin countries of TFWP permit holders in 2021 alone were from Asia: India, the Philippines, South Korea, China, and Thailand. India even topped the list with 13,560, the Philippines third with 12,725, and South Korea fifth with 2,975. Notably, Indian media ran stories on the new scheme for TFW spouses and children as soon as it was announced.

On its website, the Alberta Civil Liberties Research Centre (ACLRC) explains that through TFWP, Canadians can hire foreign nationals to fill temporary labor and skill shortages when Canadian residents are not available to do the job. First, though, a prospective TFW employer would need government approval in the form of a Labor Market Impact Assessment.

TWFs are granted entry into Canada in four categories. Live-in caregivers look after children, the elderly, or those in need. Seasonal agricultural workers meanwhile work on farms as part of bilateral agreements with specific countries, such as Thailand and the Philippines. They are only allowed to be in Canada for a limited stretch at a time and have to leave the country after eight months.

The other two categories are for high-skilled and low-skilled workers in other sectors. High-skilled workers would include academics and entertainers, while low-skilled ones do manual labor, such as sanitation work, or as Danilo de Leon, chairperson of Migrante Canada, the Canadian chapter of the Philippines-based Migrante International, puts it, jobs that “Canadians don’t want to take.”

“In Migrante,” he adds, “we call it the ‘three Ds’: dirty, demeaning, and dangerous.”

A TFW visa comes with two kinds of work permits: open and employer-specific. ACLRC describes the employer-specific permit as “‘closed,’ meaning the [TFWs] can only work for the employer listed on their work permit. While they can technically quit their job, they cannot work for another employer without having a separate work permit issued with the new employer’s name.”

“In practice,” ACLRC continues, “this restriction makes TFWs very vulnerable to exploitation, because they are very unlikely to quit their job even when working conditions are poor or pay is unfair.”

“It is bonded labor, you are literally tied to your employer,” MWAC’s Hussan says. “It’s indentured servitude.”

This seems especially true for low-skilled TFWs who are often less aware of their rights or have little or no idea of any legal recourse. Says De Leon: “Employers, managers, and supervisors use the temporary foreign worker program because they know that you will be stuck with them for two years or one year.”

Dismal working conditions

De Leon himself first came to Canada via the TFWP in 2009 on an employer-specific permit. Although he obviously did not expect red-carpet treatment with his job as janitor, the Philippine native was still appalled with his work conditions. “There was no place to sit and eat your lunch, you had to sit on the floor to eat,” he recalls. He also says that there was unfair treatment at the workplace, with migrant workers getting the worst shifts and denied overtime pay.

But Jeffrey MacDonald, a spokesperson for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, says that temporary foreign workers now have recourse under new laws.

“Everyone deserves a work environment where they are safe and their rights are respected,” MacDonald says. “The government takes the safety and dignity of foreign workers very seriously, which is why the government of Canada has been taking strong action to protect workers. Since June 2019, a foreign worker with an employer-specific work permit has been able to apply for an open-work permit if they are being mistreated by their current employer. The open-work permit allows them to quickly exit these situations and look for new work with a different employer.”

That, however, is easier said than done. Aside from a high threshold to prove that level of exploitation, the fear of reprisals is too much for many workers. York University sociology professor Dr. Luin Goldring remarks, “We know that migrant workers in these programs experience exploitative work conditions but hesitate to speak out or seek legal recourse.”

The hesitance in reporting their abusive employers may also come from hopes that continuous work would boost the workers’ chances at being granted permanent residency. Among the avenues available for TFWs wanting to become a permanent resident of Canada is a points system based on their work experience. Get enough points, and you qualify for permanent residency. Employers therefore have immense power, since they can decide whether or not to give a TFW a proof of employment letter.

There are limits to what TFWs can endure, however. In August 2022, the newspaper Jamaica Observer published excerpts from a letter that Jamaican migrant farm workers in Canada sent to their government. The letter read in part: “We are living in a First World country but at these farms rats are eating our food. We do not have clothes dryers so when it rains we are forced to wear cold, wet clothing to work. We live in crowded rooms and have zero privacy. There are cameras around the houses so it feels like we are in prison.”

The workers, who were on the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program (or SWAP), described their situation as “systemic slavery.” They wrote: “We are treated like mules and punished for not working fast enough. We are exposed to dangerous pesticides without proper protection. Our bosses are verbally abusive, swearing at us. They physically intimidate us, destroy our property, and threaten to send us home.”

Discriminated and scammed

The pandemic only laid bare the labor inequities in Canada. A July 2022 study, for instance, noted that the death of nine migrant agricultural workers from COVID-19 in Ontario could be traced to substandard living conditions and nearly non-existent healthcare monitoring, among other challenges.

“When migrant agricultural workers were concerned about overcrowded living quarters during the first two waves of COVID, there was not much they could do,” says Goldring. “In fact, it was support from advocacy groups, migrant justice organizations, and journalists that helped their situation come to light. In spite of that, migrant workers died in preventable deaths.”

Migrante Ottawa chairperson Aimee Beboso meantime says that many Asian TFWs — as well as undocumented ones — who were essential workers at the height of the pandemic were discriminated against and abused.

“Migrant workers faced racist incidents,” says Beboso. “[They were told] ‘Oh, you’re Asian? You must’ve brought the COVID virus with you.’ Many worked as caregivers and nurses. They were on temporary visas to begin with and were low-paid, so they were treated as disposable.”

The TFW program has also attracted scammers. Migrant rights activist and author Gabriel Allahdua says that TFWs getting defrauded is a very common occurrence. For every case that comes to light, he says, there are many others that do not. Comments Allahdua: “Canada is a country with a culture of silence.”

Allahdua says the scams TFWs fall prey to are “myriad.” Some TFWs, for example, become victims of “wage theft,” where an employer does not pay the worker their due; others are charged what Allahdua says are “undue recruiter fees.”

“It is the employer who is supposed to pay all the fees related to recruiting workers,” he says. “But a lot of workers pay CAD 6,000 (US$4,485) to CAD 7,000 (US$5,233) or even CAD 10,000 (US$7,476) in some cases.”

In a three-part series published in August last year, the media network CBC recounted how supposed TFWs not only paid exorbitant fees, but also wound up paying their “employer.”

CBC said that two of the TFWs had each paid recruiters in their country, Vietnam, more than CAD 60,000 (US$45,000) to work in a Prince Edward Island farm. They were assured their farm jobs would pay them more than that. But the Vietnamese said that they were not given any work for months and were even made to pay for the checks that were supposed to be their wages.

In the end, the scammed workers were granted open-work permits. CBC quoted Minister Fraser as saying, “The Temporary Foreign Workers Program, at its inception, was designed to bring workers in to fill temporary gaps in the labor force. Over time, it’s become a program to fill permanent gaps in the labor force with temporary workers. I think we can do better.”

For the ACLRC, however, the program is inherently flawed, since it was designed with employers, not workers, in mind. It observes: “They are brought in because Canadian employers requested them. This stream of immigration is driven by employers. If no one says they need the TFWs, they won’t come to Canada.”◉