|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

P

uddles of water catch the light of the setting sun in the ramshackle Rohingya settlement in Mewat, in the northern Indian state of Haryana. Women cook on open hearth stoves, amid heat and smoke in their thatch and bamboo homes. Outside, men — mostly daily wage construction workers — huddle over their mobile phones, talking about the four political prisoners in Myanmar who have just been executed by the military junta. Others discuss in hushed tones, how their acquaintances and family in Jammu are trying to return to Myanmar, fearing that if they do not, the Indian government will detain and deport them anyway. Not far away, in a fallow field still squelchy from the previous day’s showers, a motley group of boys and men kick a football around, seemingly oblivious to it all.

In reality, they are anything but oblivious. Most of these footballers fled to India within the past two decades to escape the ongoing genocide of Rohingya in Myanmar. Today they are among the young men dispelling stereotypes of Rohingya refugees across India, which has proved to be a rather reluctant host.

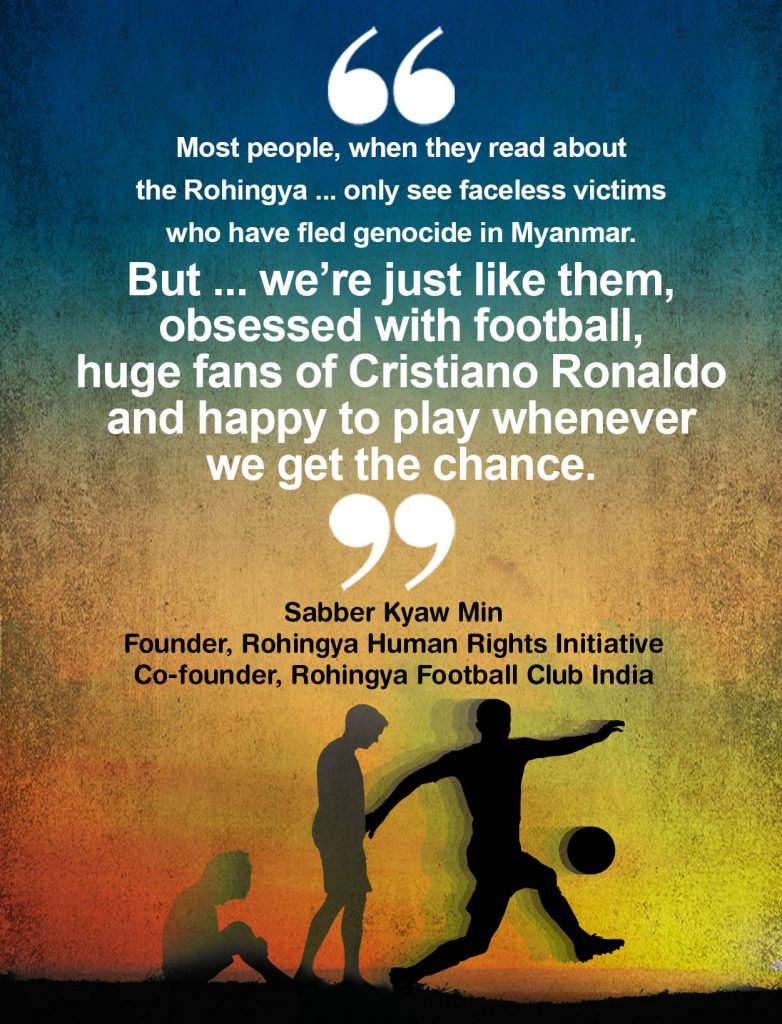

“Most people, when they read about the Rohingya in newspapers, they only see faceless victims who have fled genocide in Myanmar,” says Sabber Kyaw Min, founder of the Rohingya Human Rights Initiative and who also started the Rohingya Football Club India five years ago with fellow refugee Ali Johar. “But the fact is that we’re just like them, obsessed with football, huge fans of Cristiano Ronaldo and happy to play whenever we get the chance.”

From Myanmar’s Arakan state, Sabber Kyaw Min had first fled to Bangladesh and then walked across the border to India in 2005.

“After all these years in India, I still do not feel like I belong,” he admits. But the first time he played football after struggling to survive in India for over a decade, something changed.

“I felt at home on the field,” says Sabber Kyaw Min, “and I saw that the men I was playing with felt it too.” This, and the stories about soccer legend Cristiano Ronaldo’s work with refugees from Syria and Palestine (he is a popular icon among Myanmar youth, Kyaw Min says) made him realize transformative sports, especially football, could be for people like him.

Uniting over football

He and Johar got together with some like-minded friends, collected about INR 40,000 (about US$ 500) for jerseys and equipment and Rohingya Football Club India was born in 2017.

“Initially, we played only some friendly matches, as players found it hard to take time off from work and we had very limited funds,” says Sabber Kyaw Min. “But gradually, as players found this was a place where they could share their problems and unite as one, the team spirit grew.”

They have since developed eight teams among Rohingya youth aged 15 to 23 in Delhi, Hyderabad, Haryana, and Jammu and Kashmir. The main Rohingya FC India team, meanwhile, has 16 regular players. Given the nature of the refugee life in India, however, the numbers are very fluid and depend upon the players’ availability for each tournament.

Being a refugee in India — and a Rohingya at that — is anything but easy. While the 1951 Refugee Convention says that any individual with a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, or nationality is deemed a refugee, India is not a signatory to this convention or to its 1967 Protocol, which stipulates rights and services that the host country must provide refugees.

Consequently, although about half of the estimated 40,000 Rohingya refugees in India are registered with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), only a few have official Indian identification papers.

Noor Hafiz, for one, arrived in India in 2008 but still does not have the national ID, the Aadhar Card. Now 22 and living at the refugee camp in Mewat, he is finishing school this year; he fears that without ID papers, he may not get to go to college. He says, “I dream of becoming a doctor, but how?”

In the midst of worrying, though, Hafiz does have something to look forward to daily: “Playing in a team where everyone has had experiences and stresses similar to mine, makes me feel better.”

About 1,600 kms to the south, in another refugee camp in Hyderabad, in Telangana state, another Rohingya footballer tells a similar story.

“I see my community struggling here,” says the 28-year-old who shall be referred to in this story as Muzaffar. “Few of us are confident enough to talk to strangers, many take up daily wage manual labor as working in the formal sector requires official ID documents. But on the football field, I can briefly forget it all and at least for some time, feel normal.”

Muzaffar plays football at least three times a week, even though he has a day job with a non-profit organization and has family commitments to boot. He declares, “Football is my passion, I wish I could play more often!”

Leveling playing fields worldwide

In fact, there has been a global push to promote sports among refugee communities. Recently, the IOC Refugee Olympic Team and Olympic Refuge Foundation won the Princess of Asturias Foundation’s 2022 Award for Sports for fielding refugee teams in every Olympic tournament since 2016. They have announced similar teams for Paris 2024 and Dakar 2026. And between 2016 and 2018 alone, the European Commission awarded a total of EUR 3 million to 54 projects that used sports and physical activities to promote social inclusion and wellbeing of refugees.

Throughout April 2022 in the United Kingdom, too, premier and local football clubs organized football-related events to welcome refugees — from matches, free tickets to a game, stadium tours and more. Earlier, in 2015, the German Football League started the Welcome to Football initiative that enables young refugees to attend weekly football training, a free meal, and German lessons. This has led to 24 of the country’s professional clubs running similar schemes.

According to a 2019 review of 83 academic publications published between 1996 and 2019, playing sports alleviates stress, and enhances integration and social inclusion among refugees. Sabber Kyaw Min recalls how in an early tournament in Delhi, a team refused to play with them. “Dejected, we were sitting in the sidelines watching that team play another match when one of their players got injured,” he says. “Immediately, I offered one of our players as a substitute, and we all became friends after that.”

Over the years, more and more clubs in Delhi NCR have started recognizing Rohingya FC. Says Sabber Kyaw Min: “Earlier, when our players went to practice in a private soccer facility, they had to pay fees. When the organizers understood who we were, they waived that fee. They said they just want us to play.”

They had found a way to be recognized for their talent, not just their refugee status, and the feeling was heady. Noor Hafiz says, “In tournaments, people often came to us to say how surprised they were at seeing us playing. I made so many new friends!”

He adds, “I now feel proud that my game helps me to portray my community to others in a different light.”

Moreover, Sabber Kyaw Min says, connecting with so many Rohingya players has given him the chance to remember their lost homeland in a more positive manner. “Many of us come from relatively good families back home but as refugees in India, we’re all equally badly off,” he says.

One of the boys on the team turned out to be the son of someone who used to be a respected martial arts teacher in Myanmar. Others reminisce about their beautiful homes and fields back home, most of which have been burnt by the military in the last decade.

“Football gives us a chance to relive and celebrate our old lives,” Muzaffar says. “It’s nice.”

A welcome ‘medicine’

It is an uphill journey, though. Few Rohingya girls have stepped out to play. Muzaffar was selected for a national tournament but could not participate as he did not have an Aadhar Card. Sabber Kyaw Min is always on the lookout for sponsors, but he has had to dip into his own savings to ensure his team participates in tournaments. But then, he says, “the players find it impossible to practice, as they’re either working or studying.”

He and other Rohingya leaders have also been detained and questioned by the police on several occasions. Their Rohingya Human Rights Initiative website faces near constant attack from malicious malware as well, and they were left with few opportunities to play competitively as the pandemic went on and lockdowns ensued.

Yet, Sabber Kyaw Min is committed to scouting out talented football players among his community today, partnering with a Delhi-based sports company Leh Leh Sports to keep the momentum going.

“It’s the best way for young players to feel ‘normal’ under these circumstances,” he says. “For me, football isn’t just a game, it’s medicine.”

The ‘medicine,’ as Sabber Kyaw Min calls it, has had some unintended positive side effects. Teamwork on the field has emboldened some footballers to connect off the field as well. Before the pandemic, one of the Delhi-based teams Rohingya Shine Star FC collected over INR 40,000 (US$500) from their community of about 90 families to help the flood-ravaged state of Kerala. This was even though most of them as daily wage laborers made just about INR 300 (US$3.76) a day.

Many footballers like Sabber Kyaw Min and Muzaffar had dropped out of school because of the uncertainties of their lives. They have now decided to resume their studies. Says Muzaffar: “It’s the only way forward.”

Some time ago, he participated in a football tournament organized by UNHCR. “On the field I met some Somalians and Sudanese players and was surprised to find they were refugees too,” he says. “I realized we aren’t the only community with problems … and I realized that as long as we have a football to kick around, we will not be alone.”◉