Editor’s note: Despite the threat of COVID-19, social movements have only grown the past years, from the sustained protests in the US against systemic racial injustices to the persevering civil society groups in Hong Kong standing up against China. But almost without fail, governments have responded with violence and impunity, sending out police and security forces to try and silence the uproar.

Thailand is no exception to this international trend. Since 2020, pro-democracy demonstrations have washed over the country’s streets and have snowballed in might and influence. As the state practices less and less restraint when it comes to the use of force against protesters, violent clashes have become more frequent. In this feature, writer Yiamyut Sutthichaya, speaking with a former deputy superintendent, outlines the common police pitfalls that trigger confrontation—and how to avoid them.

On 7 August 2021, more than a thousand protesters stormed the streets of Thailand and marched toward the Government House, seat of power for Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-o-cha, calling for his resignation. In recent weeks, the public has grown increasingly discontent at how poorly the government has handled the COVID-19 crisis — and it seems they want someone new in charge.

But before long, state forces, about a hundred strong and decked in full riot gear, blocked off the protest warpath and dispersed the crowds by force, using water cannons, tear gas, and rubber bullets. The situation quickly descended into violence: police opening fire, protesters retaliating, and on both sides, wounded bodies being carted away.

The 7 August clash was merely the latest in a string of pro-democracy protests, which started in 2020, that have been met by the increasing use of force by the police. In some instances, state forces act to disperse protests even before they begin. More worryingly, the use of force has also harmed passers-by and nearby residents. In response, more and more people have leveled criticisms at the police’s crowd control guidelines.

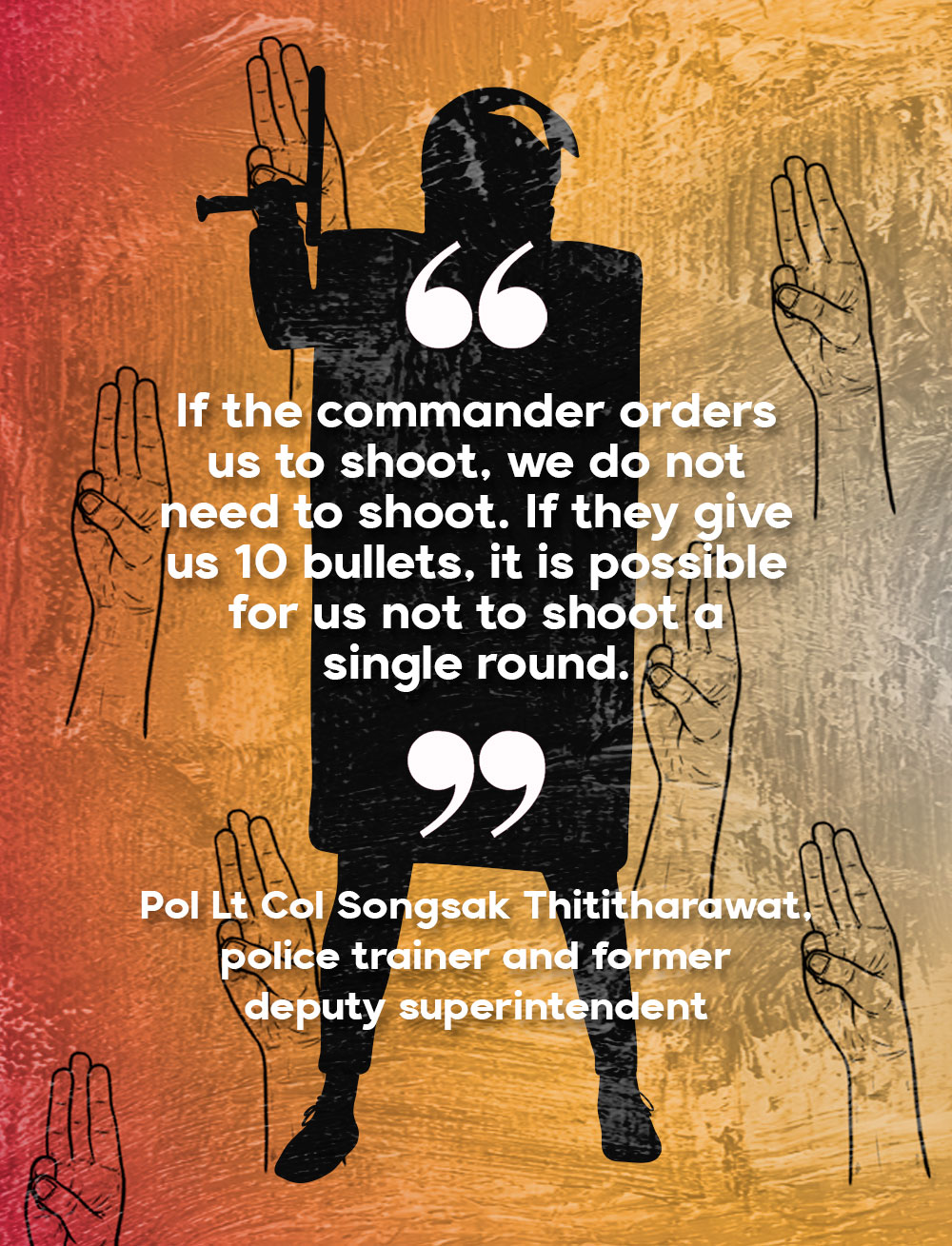

Amid the growing friction between the public and the authorities, Pol Lt Col Songsak Thititharawat, a police trainer and former deputy superintendent (General Staff Division) of the Phayao Provincial Police, said the situation is worrying and the police on the ground may not be doing it correctly.

Thititharawat says that the police’s use of force comes in levels, from making an appearance in uniform to using weapons. For crowd control, the Public Assembly Act requires officers overseeing public gatherings to be trained to understand and tolerate the situation, and be properly equipped with tools as provided by the relevant laws.

But crowd control police are not allowed lethal weapons like pistols. Instead, they can only use less dangerous weapons like batons, tear gas, and rubber bullets, which must be used proportionate to necessity, such as when protesters are likely to harm the police. The main reason for the use of force is to create space between protesters and police and to buy time to diffuse tension — not to cause bodily harm.

VA protester runs away as he is encumbered by tear gas. State forces have increasingly resorted to violence to forcibly disperse public demonstrations. But according to police trainer Songsak Thititharawat, negotiation is almost always the best approach, something that both sides do not always follow.

Skipping the guidelines

In reviewing the events of 7 August, Thititharawat says that “the first step is already wrong; there were no negotiations.” According to him, negotiations are the safest way to handle crowds.

But governments with authoritarian origins and leanings tend to reject negotiations. Thailand’s Emergency Decree, which overrides the Public Assembly Act, leaves out negotiations in its crowd control provisions. Without negotiations, conditions are liable to devolve into confrontation.

“When people take to the streets, they meet confrontation lines,” Thititharawat explains. “Naturally, there will be a contest for space: The protesters will move forward and the crowd control officers will block them.” Such a scenario will breed tension, and parties will provoke each other.

“[Crowd control], if it really follows the law, is to completely eliminate the demands. Either comply with the demands, or if you can’t comply with the demands, there may be some time factor,” Thititharawat says. What’s important is that there must be a dialogue on how to solve the problem.

“But lately there have been no negotiations. When there are no negotiations, each party will try to achieve their own goals,” he adds. “If neither party can achieve their goals, there will be conflict. Then they will use force against one another.”

When a clash happens, it’s already probably too late, Thititharawat continues. “The problem following a clash is that what is inevitable is a third hand. I always say that whether it comes from the protesters or the police, it can always appear. No matter what the objective is, it will make a peaceful assembly not peaceful.”

Generally, his reference to a ‘third hand’ may mean hardcore protesters who use weapons or explosives to make the protest look violent, or the authorities who want to legitimize their reason for a crackdown by escalating the use of force themselves. In turn, this could trap both protesters and police officers in a cycle of violent confrontation.

“If the protesters are assaulted by the police, the degree will increase the next time,” Thititharawat says. “Protesters will bring along protective equipment or something to take revenge. The police will then say ‘last time there were officers injured,’ so next time we will cut out the soft steps. We will start with the hard steps from the beginning.”

Increasingly, social and traditional media have been flooded with images and footage of police using excessive violence—stamping on protesters, shooting rubber bullets point-blank. The conflict and ensuing public outcry, according to Thititharawat, comes from the different attitudes toward democracy of the police and the protesters.

“Some people have different ideas that they have been taught. When they are on the ground, given a particular situation and concomitant pressures, and with mindsets that are not the same, the emotions will be different. Some see protesters as enemies. Some see them as relatives or friends ….,” he says.

“The situation will get more violent. If the protesters are assaulted by the police, the degree (of violence) will increase the next time. Protesters will bring along protective equipment … to take revenge. The police will then say, ‘Last time there were officers injured. So the next time around, we will cut out the soft steps. We will start with the hard steps from the beginning.'”

Using force against protesters can only result in resentment, which in turn feeds into a cycle of revenge and escalating violence. Instead, police officers should strive to be as composed as possible and to find the most peaceful way to diffuse tension during protests.

Act with goodwill

After the fierce police tactics at the 7 August protest, Thititharawat posted on his personal Facebook account, holding the police at the scene to task for the great number of rubber bullets they fired. The post commanded over 170,000 likes, but Thititharawat says that other officers asked him to “soften the tone.” He decided to delete the post.

“I wrote to tell the crowd control officers that whatever the commander orders, when you are on the ground, you can be flexible about using force,” he says. “If the commander orders us to shoot, we do not need to shoot. If they give us 10 bullets, it is possible for us not to shoot a single round.

“We can be flexible in using force by following the steps we practiced,” Thititharawat adds. “For example: first, speak to the protesters or negotiate to have them step back.” He recalls that during the 2010 crackdown on the red-shirt protesters (formally known as the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship), he was at the protest at the Khok Wua intersection in Bangkok. Instead of letting the situation escalate, he negotiated with both protesters and soldiers to retreat 50 meters in order to create enough space and prevent any third hand from interfering.

While protesters also need to have well-organized demonstrations and include protest guards who can withstand pressure and escalation, Thititharawat encouraged police to be mindful of their actions, and make decisions based on the law and goodwill toward the protesters.

“Those selected as crowd control police are mostly under 40 years of age. Actually according to the standards, they must be under 35,” he explains. “Therefore, you still have many years to go in government service. You will be at an age where your career can still go for at least 20-25 more years. Don’t forget that those who have power come and vanish.

“If you commit an act of violence — no matter if you act violently from emotion, or maybe from pressure or a special order — the consequence of your action, if ever it happens to be against the law, there is a chance that you will be sued,” Thititharawat adds. “If that happens, no one can help you, your commander can’t help you. I have seen many of my friends sent to jail and leave government service before retirement because of this reason. I don’t want you juniors to suffer that.” ●

This article was first published by Prachatai on August 19, 2021, and is republished here by the Asia Democracy Chronicles with permission.