When a modest monument to three local heroes who belonged to indigenous tribes in the Philippine north was reinstalled last April, tribal elders performed the songa, a powerful ritual aimed at punishing all who had helped ruin it months earlier, as well as to serve as a warning to anyone still wanting to do it harm.

So far, the monument is still standing. But there is no guarantee the songa would be enough to keep it from being desecrated again.

Local police had dismantled the monument in secret one night last January. The three large steel panels — etched with the faces of Macli-ing Dulag, Pedro Dungoc Sr., and Lumbaya Gayudan — that made up the monument were left on the ground, where local residents found them the next morning. Earlier, the marker explaining what the monument was about was also defaced.

While the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) has insisted that the monument is a road obstruction, many in the Cordillera Region see its dismantling as yet another proof of the police and military’s continuing distrust of the country’s indigenous peoples.

The Philippines has at least 110 ethno-linguistic groups. The National Commission on Indigenous Peoples lists 14 groups in the Cordillera Region, under which are subtribes.

Indigenous peoples’ groups have been a target of attacks by the government since the 1970s as its members have often joined advocacy groups and organized themselves to thwart threats to their land and lives. Apparently, the military and the police see most, if not all, of these groups as communist fronts.

This small village of Bugnay in the Cordillera region in northern Philippines sits above a ravine by the Chico river, where a controversial dam was to be built. The indigenous peoples who live here continue to reject any attempts to encroach on, and desecrate, their ancestral land, and will fiercely defend it — even at the risk of their own lives. (Photo by Maria Elena Catajan)

A June 2020 report on the Philippines by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) even noted: “The indigenous Lumad peoples have, for decades, been caught in a tug of war between the army and NPA (New People’s Army, the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines).”

The OHCHR adds: “Accusations based on the perceived affiliation with one side or the other are common, and often precede arbitrary detention as well as threats, violence, and killings by both State and non-State actors. Further issues arise from the role of private mining and logging companies, infrastructure projects, and large-scale agribusiness on ancestral lands, and in the implementation of the land distribution program for peasant farmers.”

Dulag, Dungoc, and Gayudan, the heroes depicted in the monument, had themselves been leaders of a local resistance against the World Bank-funded Chico River Dam project of the Marcos dictatorship (1972-1986). Dulag was assassinated in 1980 by the military. Dungoc and Gayudan continued to be active in the movement against the dam until their deaths, the former because of an accident in 1985, the latter due to an illness in 1984. The dam was never built, but the threat of new ones in the region lingers.

Right of way claims and leftist accusations

The monument is located along the Bontoc-Kalinga road in Bugnay, Tinglayan, Kalinga — some 419km north of the capital Manila — and sits just above a ravine alongside Chico River. The Cordillera People’s Alliance (CPA), a federation of grassroots-based organizations, had installed it in 2017, after 17 years of planning and coordination with the community and various organizations, following a request by the late Francis Macli-ing, son of Macli-ing Dulag.

In April 2021, these steel monuments were restored three months after they were dismantled in secret. The situation remains tense as authorities continue to insist the monument site is not where the structure belongs. (Photo by Maria Elena Catajan)

News about its impending demolition came three years later, in October 2020. Soon, the DPWH’s local engineering office issued the CPA a notice to demolish the “illegally built” monument, which it also said was an obstruction. The original request for its demolition, however, came from the Kalinga Provincial Police Office (KPPO), which said the monument was within the “right of way” of a national road.

CPA argued that representatives of the families of Dulag, Dungoc, and Gayudan, and the umili (village) from Bugnay had conducted community consultations involving the local government units for the project. It also said that the clan of Dulag had offered the parcel of land on which the monument was eventually erected, and that no problems on “road right of way” were raised even when the project was inaugurated as part of the Cordillera Day celebrations on 23 April 2017.

“(Any) activity for road widening or expansion on the monument site is impossible,” it added in a statement it issued as a reply to the demolition notice. “Road widening or expansion is only possible if done on the opposite side of the national highway toward the mountain side.”

CPA has long been considered a “leftist” organization by state authorities. Even today, its members are among those targeted by the military and police’s “surrender” campaign, which is in line with the government’s Enhanced Comprehensive Local Integration Program (ECLIP) that aims “to help rebels restore their allegiance to the Philippine government.”

Macli-ing Dulag, whose image is one of those represented in the monument, is buried near his home in Bugnay, a small village in the northern Cordillera region. Murdered in his sleep in 1980, Dulag was part of the movement that vigorously opposed the erection of the Chico River Dam, a highly controversial World Bank-funded project during the Marcos dictatorship. (Photo by Maria Elena Catajan)

In a February 2021 memorandum, the Police Regional Office (Cordillera), citing “Verbal Instruction of the Regional Director,” also directed its lower units to “encourage your respective LGUs (local government units) to pass a resolution declaring the CPA and other left-leaning organizations” as personae non gratae.

In addition, the police filed a murder case against CPA head Windel Bolinget, leading to the issuance of a warrant of arrest and a shoot-to-kill order for him. Despite a court decision last March for the recall of the arrest warrant and a reinvestigation of the case, the “Wanted with PHP100,000 (US$2,004.80) Bounty” posters bearing Bolinget’s name and photo are continuously hung along the major roads in the town where he lives.

CPA Secretary General Bestang Dekdeken meanwhile is still dealing with a cyber-libel suit filed by the police after she spoke up against the dismantling of the heroes’ monument.

Unity among tribes

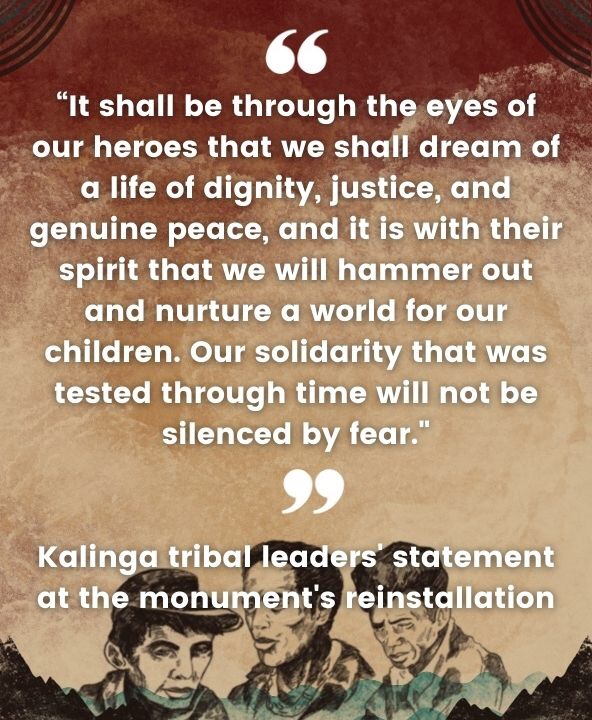

Community elders thus insisted that the monument’s reinstallation be an initiative of the community and not of groups, including the CPA. They emphasized that the action should be a collective effort to show the unity of the Kalinga tribes, the cause for which the three men had fought decades ago.

During the monument’s reinstallation last April, tribal leaders said in a statement, “The treacherous dismantling (of the monument) by policemen in the night of January 4, 2021 resurrects the memory of that tragedy when a gang led by Lt. (Leodegario) Adalem stealthily swooped in the village and murdered Macli-ing Dulag in his sleep and wounded Pedro Dungoc Sr. in the dead of night. It is against paniyaw to remain silent while a monument that immortalizes the heroism of those who dared to put their lives on the line to defend the land is desecrated.”

(Paniyaw is a code by which the Kalinga folk live in relation to the Creator, their fellowmen, and other creations of the Creator. The code speaks of respect for life, dignity of man, harmony, and community in the tribe, as well as of the continuance of the natural processes of what makes up the earth and the environment from which the people get what they need to live.)

The statement also said, “It shall be through the eyes of our heroes that we shall dream of a life of dignity, justice, and genuine peace, and it is with their spirit that we will hammer out and nurture a world for our children. Our solidarity that was tested through time will not be silenced by fear.”

The police have yet to say anything about the monument’s reinstallation, while the DPWH has offered to “move” the monument and create a “park” for it. But the National Historical Commission of the Philippines has weighed in, backing the preservation of the monument even as it says that it falls under the local government unit’s jurisdiction. According to the Commission, “monuments of our heroes, illustrious personages and leaders of the locality, should be treated with utmost respect and reverence.”

For Beverly Longid, International Solidarity Officer of Katribu, the national alliance of indigenous peoples’ organizations in the Philippines, the monument symbolizes a successful struggle of a people, which the government is now too scared to have Filipinos relive and remember.

“It is the first World Bank-funded project rejected by the people at the time of martial rule in the country,” she says. “They were successful in stopping the project … It became an inspiration for many, cinematic even. It was a collective experience. And the government is too scared to give people that kind of motivation.”

“The valid struggle of the Chico irrigation project continues but in a different form. … (T)his true, concerted effort to revise history serves as a reminder to keep the narratives going … (for people) to become their own Macli-ing Dulag, Pedro Dungoc Sr., and Lumbaya Gayudan — to keep their memory and what they symbolize alive.”●

Maria Elena Catajan is a journalist based in the north of the Philippines.