The Games must go on!

That has been the battle cry of the Japanese government and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) regarding the much-delayed 2020 Summer Olympics. But as they doggedly push on to have the Games finally take place this July and August in Tokyo, the capital city, they seem to be losing even more support from an already wary Japanese public.

In a nationwide poll conducted last 19 June by The Mainichi Newspapers, 42 percent of the respondents said that the Tokyo Games should be either “cancelled” or “postponed again,” while 31 percent of respondents said that it should be “held without spectators.”

Meanwhile, an online petition that on 5 May began calling for the Games to be cancelled has received around 430,000 signatures so far, while a Twitter hashtag “We demand the cancellation of the Tokyo Olympics” has been trending.

The Tokyo Games were postponed last year due to the COVID-19 pandemic and rescheduled to start this 23 July. But Japan is still in the midst of what is said to be its “fourth wave” of infections and there have been worries that a massive influx of athletes and sports officials from all over the world could result in even wider spread of the virus.

Indeed, observers have pointed out that the government and the Tokyo Organizing Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games seem to have their lines crossed. Plans for the games, for instance, include allowing up to 10,000 spectators, which apparently comes from consideration for Olympics stakeholders. Yet the government keeps asking the public to refrain from going out and having mass gathering as infection countermeasures – with good reason. Although the third state of emergency in Tokyo was lifted last 20 June, the number of infected people in the capital has since resurged. Too, as late as last 21 June, only about seven percent of Japan’s population of 126 million have been vaccinated.

Scheduled to start on July 23, 2021, the Tokyo Olympics have been hounded by domestic worries that a massive influx of athletes and sports officials from all over the world could lead to even wider spread of the coronavirus in Japan.

A potential global superspreader

Japan’s total confirmed COVID-19 death rate remains lower than many other countries, but its medical system has been under strain since the first wave of coronavirus infections hit last year. The Japanese medical community has been repeatedly warning the government that holding the Games could trigger not only a resurgence of the infections in the country itself, but could also trigger a global spread of different variant of the virus once the athletes and all the other outsiders who came for the Olympics go home.

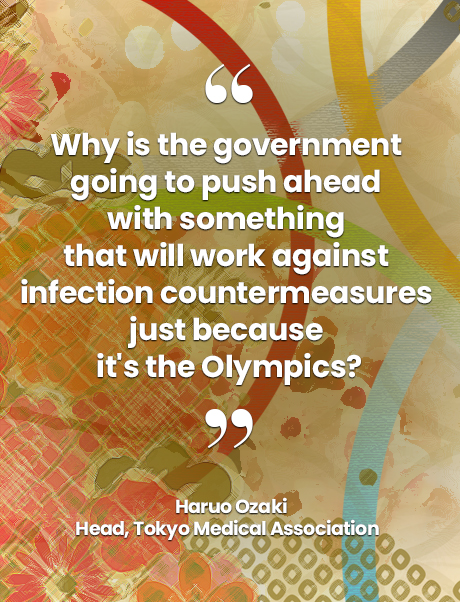

Tokyo Medical Association head Haruo Ozaki has criticized the government regarding the Olympics. In an interview with The Mainichi this month, he called the potential danger posed by holding the Games at this time as “incomprehensible.” Ozaki, who is treating COVID-19 patients at his own hospital, added, “Why is the government going to push ahead with something that will work against infection countermeasures just because it’s the Olympics?”

This would actually be the second time that Japan would be host for the Summer Olympics. It was host for the Games in 1964, the first time the Summer Olympics was held – also in Tokyo — in an Asian country.

In 2011, Tokyo submitted a bid to host the 2020 Games, following its failure to win the rights to host the 2016 Summer Games. Those bids were originally led by then Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara, a popular novelist and right-wing politician. In 2012, Tokyo won the bid to host the 2020 Summer Olympics, beating Istanbul and Madrid, thanks to the central government’s full support.

Public support for the Games, however, has been another story – even before the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the IOC’s own polls conducted in Tokyo, only 55.5 percent of respondents supported the bid for hosting the 2016 Games, and that showing was the lowest level among the then five competing cities. The support rate among Tokyoites rose to 65 percent before the second bid (for 2020) according to a survey conducted by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, but the public sentiment across the country remained lukewarm.

One of the major reasons for such comes from the opportunistic change of the concept and purpose for the Games as delivered by the government and the organizers. At the first bid for the 2016 Games in 2009, they announced the concept of a “green” Olympics that would reduce carbon emissions from Games-related projects. The second bid took place in 2011, just after the massive earthquake and tsunami hit the east part of Japan and caused Fukushima nuclear disaster. Then Tokyo Governor Ishihara said that the bid was a symbol of Japan’s recovery from the disaster, declaring, “If we will work hard with hopes for nine years ahead, it will be a big catalyst for our country’s reconstruction and revival.”

This was reiterated by Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga last 17 June, when he announced that the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympic Games would push through as planned. Said Suga: “The Games will be an opportunity to send out to the world a message showing our recovery from the Great East Japan Earthquake and to convey dreams and profound emotions to children.”

July 2020. Donning face masks to shield themselves against COVID-19, a crowd of commuters are on their way to work during the morning rush hour near the Shinjuku station in Tokyo.

A hollow slogan?

Yet while “Recovery Olympics” has emerged as a slogan for the 2020 Games, it has sounded hollow at times.

In 2013, at the final presentation for the 2020 Games in Buenos Aires, then Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe assured IOC members that the three nuclear reactors in Fukushima that had been damaged in the 2011 quake were “under control.” Up to now, however, the government is struggling with the huge amount of radioactive-contaminated water discharged from the crippled reactors on a daily basis.

Former Tokyo Governor Ishihara’s remarks about holding a “Recovery Olympics” also turned out to be less than truthful. In an interview with The Mainichi in 2019, five years after he retired from politics, he said, “I did not intend to connect Olympics to recovery. Recovery Olympics must be a government official’s skillful rhetoric.”

According to Ishihara, his real intention for having Japan host the 2020 Games was “enhancement of national prestige.” He said that he felt frustrated over not seeing enough Japanese victories in the 1964 Tokyo Games and wanted “revenge.”

And yet the Japanese athletes’ performance at the 1964 Games was not at all bad. According to reports at the time, most people in Japan were excited over the athletes’ achievements, which included 16 gold medals, as well as five silver and eight bronze ones. Japanese athletes have delivered as well in succeeding Games, garnering a record high of 41 medals in the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro.

In any case, Prime Minister Abe had also kept saying “Recovery Olympics” in talking about the 2020 Games. But this became less frequent after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead of mentioning the devastating earthquake, Abe started saying that holding the Olympics would be “proof that humankind had triumphed over the coronavirus.”

Message fails to connect

Abe resigned in August 2020 citing health reasons, and after the postponement of the Games was decided. His successor Suga has kept the same line he last spouted. In a debate held at the Diet last 9 June, Suga said, “I want to deliver a message from Japan to the world that we can overcome the difficulty of the coronavirus pandemic.”

But it’s a message that the Japanese public is finding hard to connect with, given their disappointment with the government’s handling of the health crisis. Kiyoshi Abe, a sociology professor at Kwansei Gakuin University who has studied public opinion regarding the Tokyo Olympics, also said in an interview with The Mainichi in 2018, “In 1964, people could synchronize their personal life to host the Olympic Games, which represented the remarkable recovery from the defeat in World War 2 with economic growth and coming back to the international community. However, the 2020 Games have failed to show people what it is for and where it is going.”

But it’s a message that the Japanese public is finding hard to connect with, given their disappointment with the government’s handling of the health crisis. Kiyoshi Abe, a sociology professor at Kwansei Gakuin University who has studied public opinion regarding the Tokyo Olympics, also said in an interview with The Mainichi in 2018, “In 1964, people could synchronize their personal life to host the Olympic Games, which represented the remarkable recovery from the defeat in World War 2 with economic growth and coming back to the international community. However, the 2020 Games have failed to show people what it is for and where it is going.”

Making matters worse are the scandals unrelated to COVID-19 that have been bedeviling the Tokyo Organizing Committee for the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Earlier this year, committee head Yoshiro Mori was reported to have said that “executive board meetings with many women in them take a lot of time.” This remark, likely in violation of the Olympic Charter, prompted strong criticism on social media as sexist, and led to hashtags like #Moriresign. The 83-year-old ex-premier was forced to step down, giving way to former athlete Seiko Hashimoto.

A month later, Tokyo Games creative director Hiroshi Sasaki resigned as well. Sasaki admitted that in online “brainstorming exchanges” with staff, he had suggested that popular female entertainer Naomi Watanabe, who is heavyset, perform at the Games opening ceremonies as an “Olympig.” The remark was criticized as being not only sexist but also an example of “lookism” or discrimination based on physical appearance.

Then the third and fourth COVID-19 waves hit Japan. As people grew more concerned, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government abandoned its plan for public viewing events of the Games.

It had planned to set six venues for free live screenings in Tokyo. As soon as the pruning work began at Tokyo’s Yoyogi Park in May, however, the scheme came under fire on social media; an online campaign opposing it collected more than 100,000 signatures, and a protest was held on the street near another venue as well.

Last 19 June, Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike announced the cancellation of the plan. Some of the six venues including Yoyogi Park will now be used as vaccination sites. ●

Satoshi Kukasabe is an award-winning journalist who writes for The Mainichi Newspapers.