On March 27, 2021, Myanmar celebrated its Armed Forces Day, which commemorates the day the Tatmadaw, the Burmese military, started its resistance against Japanese occupation.

Under the weary sky, platoon after platoon of uniformed – and face-masked – military personnel marched through the event grounds in Naypyidaw. Some were carrying flags, others rifles, flags, or batons. Right behind them rolled a caravan of trucks and tanks and anti-air missiles. High above flew a small fleet of copters.

Since the coup on February 1, 2021, protests have swelled across the nation. Under the banner of the Civil Disobedience Movement, civilians, normal everyday people, have stood up against the junta, unwavering even in the face of violent crackdowns.

Tensions between protesters and the military have since turned bloody, and in recent weeks the Tatmadaw have let go of any pretense of respect for peaceful dissent. In response, the civil uprising has rejected the 2021 Armed Forces Day, and instead labeled it as the Anti-Fascist Resistance Day. With more ferocity than usual, protests erupted across the country, calling for an end to the military rule.

The Armed Forces Day is supposed to be a celebration of the country’s struggle for independence, and the parade is ostensibly a demonstration of its might and unity. That same day, the Tatmadaw dropped bombs and opened fire on protesters across the country, ultimately killing dozens of people.

Refused refuge

In the days that followed, the Tatmadaw continued their air strikes, dropping bombs on villages within the Karen National Union’s territory, in southeast Myanmar, bordering Thailand.

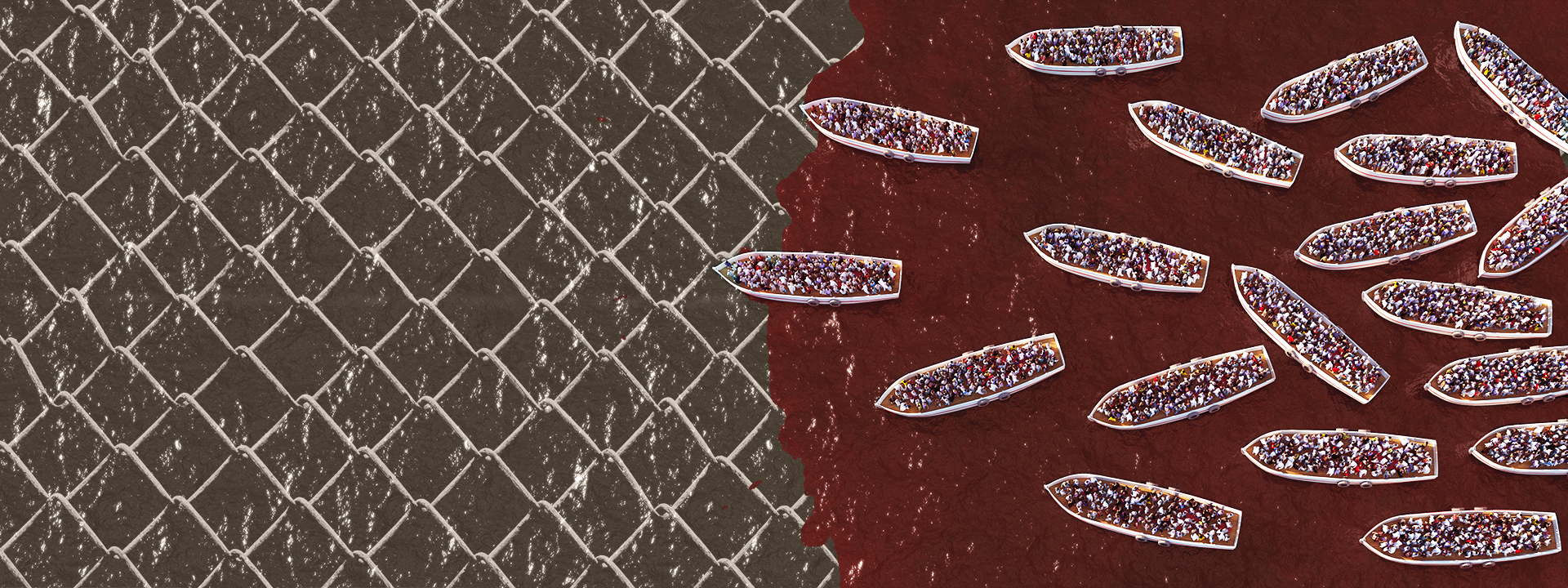

With their houses in ruin and their lives in danger, civilians were forced to leave their homes behind and scramble for safety. Over 2,000 refugees tried to flee into Thai soil, but were pushed back by border security.

Saw Pee was one of the people who were refused entry, and had no choice but to retreat to the Ei Tu Hta refugee camp, which rests along the Myanmar-Thailand border, still within the Karen State. According to Saw Pee, the Thai guards were convinced that there would be no more air strikes, that they would be safe in their homes, and that they should turn back. After the refugees left, Thailand beefed up their border control.

“They placed barded wires along the route to the border so that we couldn’t return,” Saw Pee said. “They said that they guaranteed that the Burma Army wouldn’t bomb the camp. We went back, but we didn’t dare stay in our homes. We hid and slept in caves, streams, and in the jungle.”

Another villager from Ei Tu Hta was even able to film the Thai army’s boats turning away Burmese refugees. In the video recording, a woman said: “We heard on the news that the Thai Prime Minister denies refugee deportation. But they [Thai soldiers] don’t want us to stay on their soil.”

“Never mind food and medicine, they don’t even want us to be on their land,” said the villager.

In a press conference, Thailand Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha told the media that Thai soldiers weren’t forcing refugees to return home; rather, the Burmese were turning back voluntarily. In fact, according to Prayut, their border control forces would even shake hands with the refugees and wish them well on their way.

But all along the border, ethnic Karen villagers were seeking refuge in Thailand, and at every turn, they were denied. People from the Way Bu Hta, a village along the Salween river, which flows along the Thai-Myanmar border to the Andaman Sea, fled to Thailand on March 28 for fear of air strikes. They were able to enter Thai soil and stay there for two days, but were eventually forced back out by armed personnel.

“They [Thai authority] said it was safe to go back. They said if there ever was another air strike, we could cross the river again,” said a mother of two, who lived with her family in Way Bu Hta. Like other refugees from other camps, the Way Bu Hta villagers learned that home was no longer safe, and that looking for shelter in the wilderness was wiser.

Gillian Triggs, Assistant High Commissioner for Protection at the United Nations refugee agency UNHCR, said in a statement: “We urgently call on countries across the region to offer refuge and protection to all those fleeing for safety. It is vital that anyone crossing the border, seeking asylum in another country, is able to access it.”

“Children, women, and men fleeing for their lives should be given sanctuary,” the statement continued. “They must not be returned to a place where their lives or freedom may be at risk. This principle of non-refoulement is a cornerstone of international law and is binding on all states.”

The UNHCR also said that they, along with partner organizations, are prepared to extend help to neighboring states in order to ensure that refugees receive the protection they need.

Diplomatic waves

But the problem is growing notwithstanding such assurances. More and more, the ripples of the turmoil in Myanmar are swelling into diplomatic waves sweeping the continent, and soon, the situation may vortex out of control.

Within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), for example, there’s hardly a consensus on how to approach Myanmar. Some member states agree that the unrest is a regional matter, and that the regional bloc should step in; others, however, believe that the issue is internal, and that they have no business interfering.

In an informal meeting on March 2, it had been decided that the ASEAN would reach out to Myanmar, taking three steps: appoint an envoy or delegation, set up a mechanism to address the crisis, and find out what kind of assistance the country needs.

“These [measures] should be agreed among ASEAN members including Myanmar,” explained Yuyun Wahyuningrum, Indonesia representative at the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights. “These three issues have not yet been decided by the ASEAN members.”

Several individual member states have spoken up about the situation in Myanmar. Singapore foreign minister Vivian Balakrishnan has called Myanmar crisis “an unfolding tragedy” that will take time to overcome, and said it was essential for ASEAN nations to have a position on how to respond. Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines have all pushed for an urgent high-level meeting. On the whole, however, the Association seems to be dragging its feet.

Meanwhile, the crisis in Myanmar has also forced hundreds upon hundreds of activists, politicians, civil servants, and media workers to flee not only to Thailand, but also to Bangladesh and India.

Meanwhile, the crisis in Myanmar has also forced hundreds upon hundreds of activists, politicians, civil servants, and media workers to flee not only to Thailand, but also to Bangladesh and India.

In turn, this could put countries like India in a tough diplomatic spot because of their close ties with the Tatmadaw, according to a report from Reuters. For instance, while India’s foreign ministry has expressed “grave concern” over the situation in Myanmar, its central government has ordered stronger border security.

At the highest level, Myanmar has also become the newest battle frontier for the world’s superpowers. According to Wahyuningrum , while the UK and US have been piling pressure on the junta to end the coup, China and Russia insist that it is an internal matter, even going as far as defending Myanmar at the UN Security Council.

But as states straddle diplomatic lines and catch each other in deadlocked debates, the people of Myanmar continue to suffer. For UK-based veteran Burmese analyst Maung Maung Than, the stakes are high and the timeline is unforgiving.

“As the whole world has witnessed the escalating bloodbath and atrocities of the regime, it is high time for the international community to take immediate action or else [we will all be responsible for] the gross violations of human rights and crimes against humanity,” he said.

All photos are from the author unless stated otherwise.

Saw Yan Naing has written for The Irrawaddy, Bangkok Post, Asia Times Online, BBC Burmese, Global Investigative Journalism Network, and others. He is currently a technical lead and media trainer at Internews.