Suntalamya dreads the ringing of her phone these days. The “safa tempo” driver in Kathmandu, Nepal, is being hounded by the bank to pay back a loan that she used for the treatment of her medical condition. She was counting on her earnings as a driver of a small electric three-wheeled minibus to pay the loan. During the nationwide lockdown from March to July 2020, however, she was unable to work.

Suntalamya and her fellow women safa tempo drivers provide an essential service and a zero-emission transport option. But even so, they struggle to earn a living amid the pandemic and get no support from the state. To make matters worse, they face gender-based violence as well.

Tempo is the generic name for three-wheelers in Nepal. Safa (which means “clean”) tempo is called “a clean three-wheeler to differentiate it from the other tempos on Nepali roads which run on diesel, compressed natural gas, or petrol,” wrote Benjie de la Peña, CEO of the Shared-Use Mobility Center and chair of the Global Partnership for Informal Transportation, which works with informal transportation systems of the Global South to advance innovation, improve services, and change business models.

The women safa tempo drivers live precarious lives. They cannot work, barely have money for food, and cannot afford the hefty costs of plying their trade.

“It is this kind of precarity where the government needs to step in, where a reframing of informal transportation as asset, rather than local problem, could really help,” wrote de la Peña.

Safa tempo driver Kumari Lama feels like there are “a hundred thousand eyes questioning [her] daily” as people think, “oh, you are a woman, how can you be a good driver?”

Lost independence

Tempo driving allowed the women drivers to earn a decent wage and to gain independence. Suntamalya is a divorced woman with grown-up children who have their own families. “I have to support myself financially,” she said. Driving the safa tempo for the last ten years allowed her to do that.

For Bhawani, another safa tempo driver, driving her own electric vehicle for the past seven years was a godsend. She is a mother who has been single-handedly raising her two children.

Bhawani learned how to drive a safa tempo in 2015, while she was pregnant with her second child. At the time, an NGO collaboration with the Council for Technical Education and Vocation Training in Putalisadak, an economic hub in the capital, offered a course in tempo driving, as well as training in tailoring and beauty care services.

Bhawani, who used to work in a beauty salon, knew that “spending a whole day there would not earn enough to provide for my family.” So she chose the safa tempo driving course.

It was a decision that paid off. “Everything was running smoothly before the pandemic,” she said. “I earned as much as 35,000 Nepalese rupees (about US$300) a month, took care of my family, and could even send some money to my husband in jail.”

No steady income

Bhawani welcomed the steady income, as neither her relatives nor her husband’s family gave her any financial support. Both families disapproved of the inter-caste marriage.

Sadly, the lockdown put an end to the women’s financial independence. After the lockdown was lifted in July, they were allowed to carry only six passengers — half the capacity of a tempo — in order to provide a safe distance between passengers.

“I was not able to provide for my family due to lack of work,” she said. After a month, Bhawani decided to go to her sister’s place in another village to seek help. Despite the lifting of the lockdown, she has not returned to Kathmandu to work.

“I was not able to provide for my family due to lack of work,” she said. After a month, Bhawani decided to go to her sister’s place in another village to seek help. Despite the lifting of the lockdown, she has not returned to Kathmandu to work.

Suntalamya also stopped driving because she could not make ends meet. She only earned 200 Nepalese rupees (about US$1.72) a day — hardly enough to cover the 400 Nepalese rupees (US$3.43) per day that she had to pay the owner of the safa tempo. Suntalamya also needed to pay the charging station; safa tempo batteries need frequent charging. She now struggles to find the money to buy her food.

A hefty fee

Amid such a trying time, Suntamalya, Bhawani, and other women safa tempo drivers receive no support from the state. Local organizations distributed a few kilos of rice, flour, and relief goods only during the first month of lockdown. Kumari Lama, a safa tempo driver herself, said that she and other women tempo drivers collected the goods and distributed them among the neediest women.

In addition, the women drivers are required to pay a registration fee of 9,500 Nepalese rupees (about US$81) to cover a three-year period before they will be allowed on the road. Lama and her organization are demanding the scrapping of this requirement.

She has not paid the hefty registration fee herself because she can’t afford it. The women face another financial burden as many of them need to buy new electric batteries for their vehicles. After the four-month lockdown, during which the tempos were not used, the batteries needed replacement or repair. A new battery costs an estimated US$859.

Of the 350 registered safa tempo drivers in Kathmandu Valley, almost half — 150 — are women.

Horror stories

A decade ago, it was rare to see a Nepalese woman in the driver’s seat of public vehicles in Kathmandu. Today, out of the 350 registered safa tempo drivers in Kathmandu Valley, 150 are women, said Lama.

Unfortunately, every woman tempo driver has horror stories to tell about the hazards of being a female in a male-dominated field. Lama feels like there are “a hundred thousand eyes questioning [her] daily” as people think, “oh, you are a woman, how can you be a good driver?” Many female tempo drivers have been subjected to inappropriate touching by male passengers and rough talking by the traffic police.

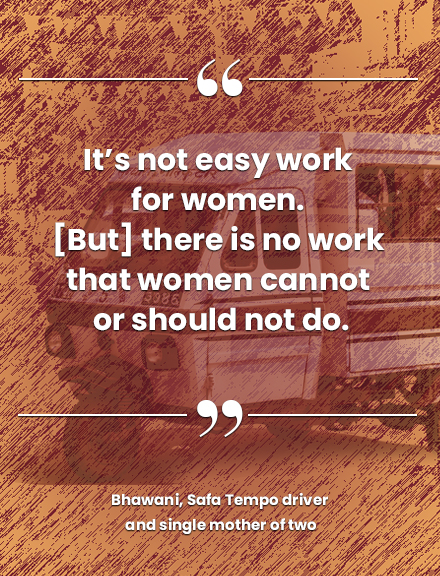

“It’s not easy work for women,” said Bhawani. Her sister, who also drives a tempo, even discouraged her from learning the trade, but Bhawani ignored her. “I thought I have to be strong and tough,” she said. “There is no work that women cannot or should not do.” ●

Kavita Raturi is an independent researcher and writer based in Kathmandu.

The two-decade-old technology and vehicles are showing their age.

A missed opportunity

Even before the coronavirus crisis, the safa tempo has faced many challenges. For one, the technology and vehicles are showing their age.

The electric three-wheelers have been steadily servicing the city of Kathmandu for 20 years, according to IPS. They run on heavy, old-style, deep-cycle lead-acid car batteries — three at a time, with six in total on board, noted Benjie de la Peña, CEO of the Shared-Use Mobility Center. “They could be upgraded (with lithium-ion technology, for instance), but the informal nature of makeshift mobility means the drivers and operators can’t access credit,” he wrote.

It hasn’t helped either that the government has not invested in the electric three-wheelers. “The electric vehicle industry is uniquely suited to Nepal because of its immense hydropower potential, which was predicted to be sufficient for all electricity and fossil fuel use in the country by 2020,” according to IPS. Yet in 2005, the government refused to let the safa tempo operate on more commuter routes and began importing diesel-powered minibuses, according to Scientific American.

By Asia Democracy Chronicles