Choi Mi-yeon had just started job hunting when she bumped against what has been described as one of the thickest glass ceilings in the world.

The Seoul resident, who studied international trade in Europe, was shocked by the questions she was asked during job interviews. “I had interviews at several mid-sized Korean companies and was asked if I planned to marry,” she said in an interview with The Guardian. “One [prospective employer] even told me it would be difficult for them if I got married as they would have to grant me paid maternity leave.”

Choi’s story is par for the course for South Korean women who “struggle to get hired by companies that only want men,” reports CNN. Before the pandemic, they already regularly faced questions about their marriage status and plans for having children when applying for a job, or suggestions that jobs in fields such as sales aren’t appropriate for women. The COVID-19 pandemic, a seemingly bulletproof glass ceiling, and a patriarchal society have severely restricted the career and life options of Choi and her sisters.

An alarming trend

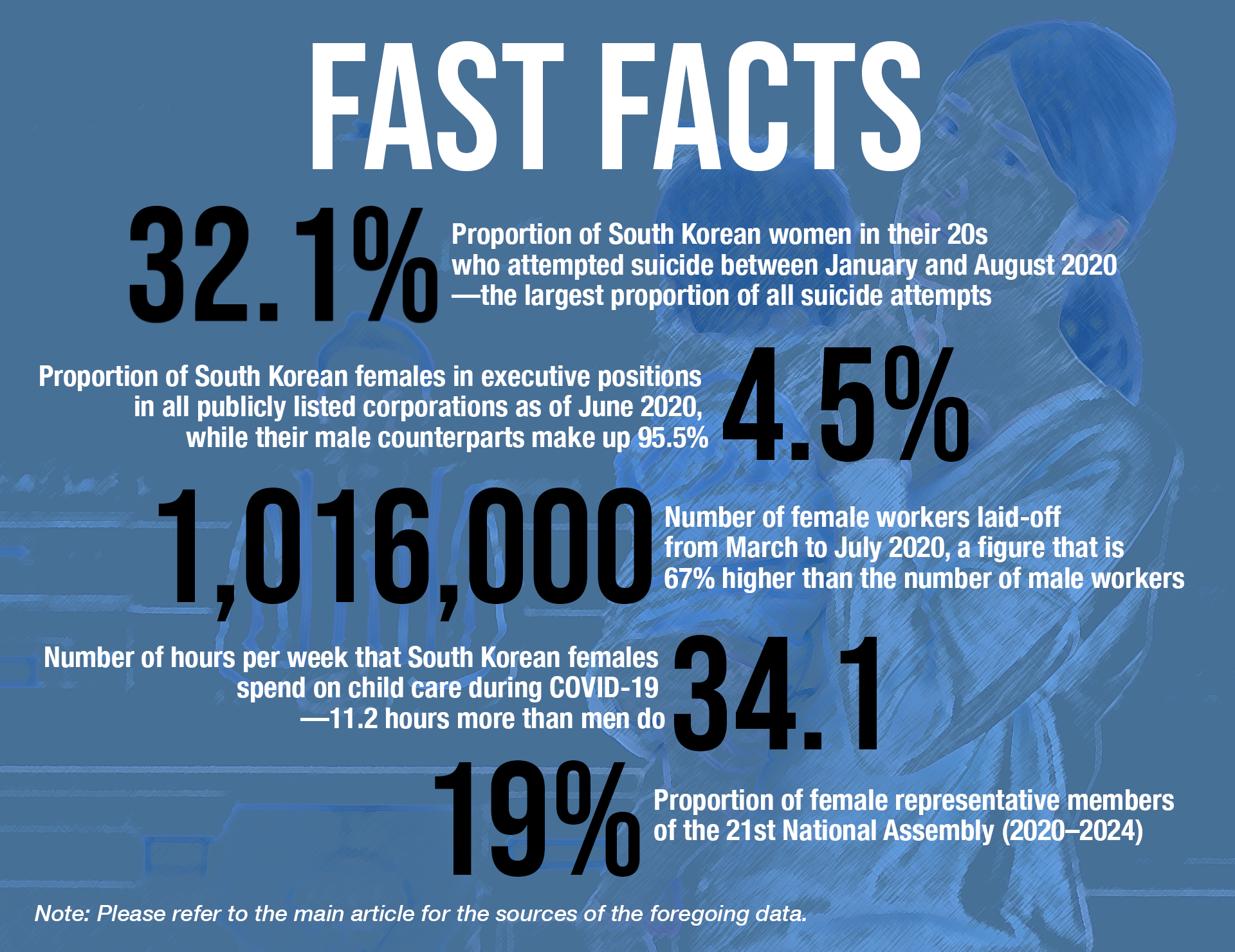

South Korea has seen a sharp rise in the number of young women who took their own lives during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, the suicide rate among women in their 20s rose by 25.5% from the year before, reports The Hankyoreh. Between January and August 2020, women in their 20s made the largest proportion of all suicide attempts at 32.1%. While the suicide rate for males is still roughly two to three times higher than that of women overall, the increase in the rate for young women far exceeds those of other generations and genders.

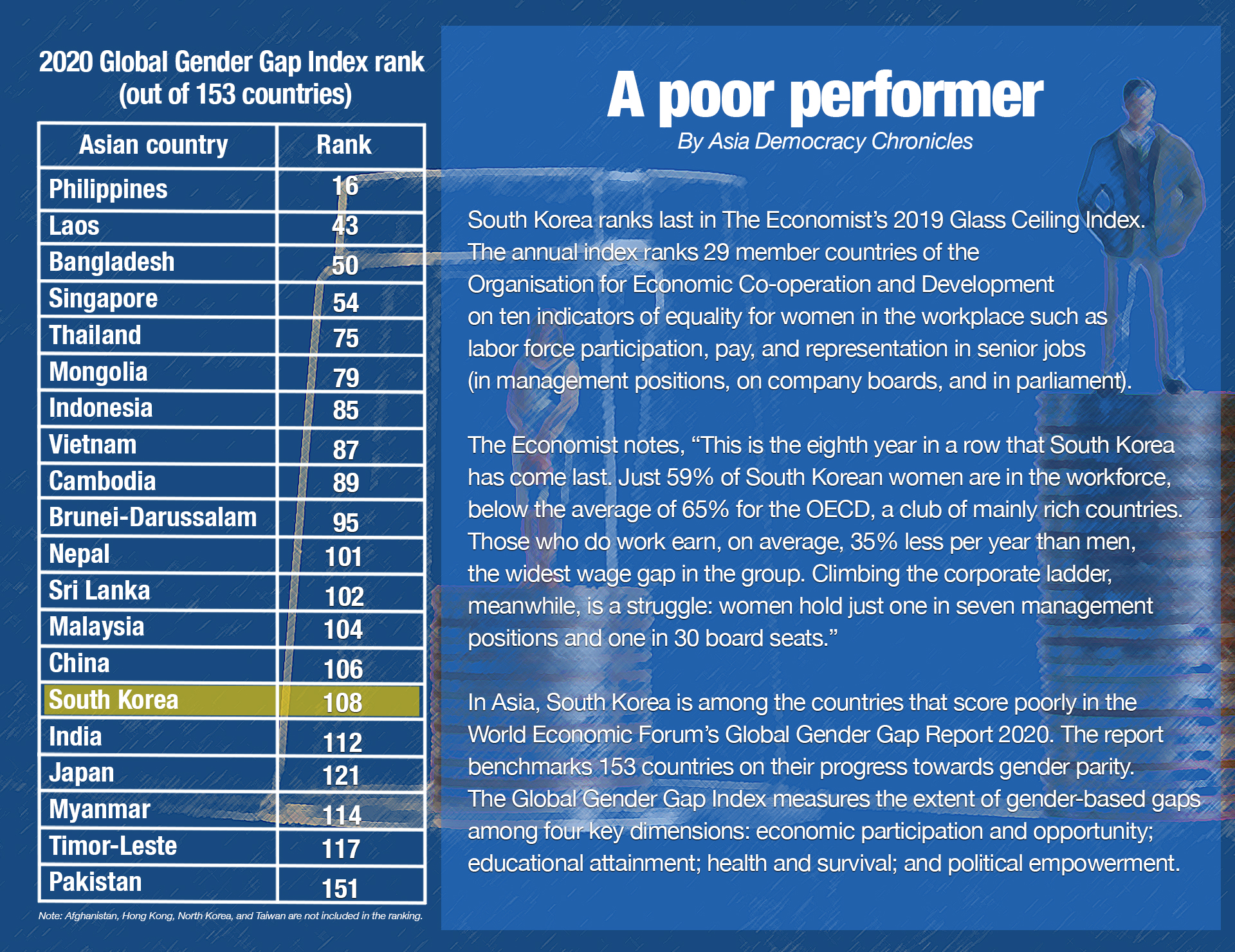

What are some of the factors behind this alarming trend? For one, South Korean male workers often get the plum jobs. As of June 2020, only 1,395 (4.5%) South Korean females held executive positions in all publicly listed corporations, compared to their 29,402 (95.5%) male counterparts.

This has led women to end up in low-paying service jobs, such as those in the hotel and food service sectors. “Since the service industry has suffered the biggest blow from the COVID-19 situation, women in their 20s have also been hit the hardest,” said Im Yoon-ok, an advisory committee member for the Korean Women Workers’ Association.

According to the Korean Women Development Institute, in September 2020, the unemployment rate for women stood at 3.4%, an increase of 0.6% from the same month in 2019. The unemployment rate for women in their 20s was highest at 7.6%.

For the period from March to July 2020, 1,016,000 female workers were laid-off. This figure is 67% higher than the number of male workers, which was 608,000. More women in their 20s saw their debt or outstanding payables increase.

To make matters worse, “a large number of young females are not covered by employment insurance so they don’t have access to government subsidies that officially registered workers can get,” reports the South China Morning Post.

A heavy workload at home

Societal attitudes towards gender roles in South Korea have been slow to change. Care work—whether paid or unpaid—is still thought of as being mainly “women’s work.”

Majority—92.5%—of the country’s healthcare workers are female. As they face health risks and work long hours, some women who feel unable to take care of themselves may suffer mental health problems. Although the government and the media laud the sacrifices of healthcare workers, there has been no tangible effort to improve their situation.

At home, South Korean women bear the burden of unpaid care and domestic work. They spend an average of 34.1 hours per week on child care during COVID-19—11.2 hours more than South Korean men do, according to a 2020 report by UN Women.

The phrase, “three meals a day” has acquired a new meaning as women at home have no time to rest as they have to prepare all the meals. With kindergarten schools closed and K-12 school openings repeatedly postponed, career women’s work-life balance today is no different as before the outbreak. All mothers are expected to check their children’s health and keep records in accordance with the government’s COVID-19 preventive measures. As a result, 62.3% of the applicants for family-care leave are women.

South Korean women are considered second-class citizens in an otherwise progressive country.

An uphill battle

While COVID-19 has amplified the discrimination against women in South Korean society, gender-based discussions are rare. In the political arena, for example, women’s representation is weak.

Female representatives account for only 19% of the members of the 21st National Assembly (2020–2024), with their age averaging 54.9 years. In a National Assembly over-represented by middle-aged men, the congresswomen are perceived and treated not as colleagues but as “young women.”

“Almost all male politicians, regardless of being progressive or conservative, are traditionalist when it comes to rights of women,” said Lee Soo-jung, a criminology professor at Kyonggi University, in The Japan Times. Therefore, introducing new laws that prohibit all types of discrimination and raise awareness on inequity is not easy.

The continued condonation of well-entrenched discriminatory beliefs and practices, especially in the midst of a pandemic, is hurting South Korean women the most. However, discussing gender equality is impossible when women are not even wholly entitled to such basic rights as freedom from discrimination.

Pandemic or no pandemic, it is clear that South Korea still has a long way to go before it attains a gender-equal society—one that has a gender-neutral labor market, the value of unpaid care work is appreciated, and women have a say in the political arena. ●

Park Eun-joo is an activist working with the Korean Women’s Associations United in Seoul, South Korea.