When we arrived at Cox’s Bazar, most of the hills around had a green cover of trees and forests, but not anymore,” recalls Mohamad Tofail, 24, who along with his family of four, has lived in the largest refugee settlement in southern Bangladesh since fleeing Myanmar in 2017. Together they traveled on foot, by boat, and small autos called tom-toms to complete a seven-day journey from Rakhine in western Myanmar.

In August 2017, over 700,000 Rohingya Muslims poured into Bangladesh to escape military-led killings, rape, torture, and arson in Myanmar. They joined an estimated 300,000 Rohingya who had fled westward, crossing the border in waves, since the 1970s to escape atrocities.

Thousands of Rohingya lived in the Cox’s Bazar coastal district in the early 1990s after fleeing persecution from the Myanmar military. Their number began to swell following the 2017 state-sponsored violence in the conflict-torn Rakhine state — their home for generations.

Today, two of Cox’s Bazar’s sub-districts, Teknaf and Ukhiya, located near the Arakan state of Myanmar, bordering Bangladesh, host over one million refugees who occupy 34 resettlement camps.

Until recently, the coastal town was a significantly habitable place, with its lush and green vegetation.

“Once-lush forests have been cleared for the camps and the road to Cox’s Bazar, the nearest major town, is clogged with aid trucks,” said a Reuters article. “A trip that used to take an hour can now take four on rutted, broken roads.”

Also, living conditions in the resettlement site are generally unhygienic: bathing facilities are shared, and access to water is limited. Jobs are scarce and education opportunities are few.

These, and the environmental degradation of a newfound home, seem to echo the unrelenting sufferings of a people long denied citizenship by a Buddhist-majority country and dubbed one of the most persecuted minorities in the world.

As pressure mounts on the coastal district, and amid the risks of COVID-19 spreading across the camps, relocation to a remote island deemed unfit for habitation poses yet another threat to the refugees’ survival.

Trading forests for homes

When the Rohingya refugees relocated to Cox’s Bazar, they built their new settlement almost overnight using natural resources in the vicinity. Today, these makeshift dwellings are changing the environment and becoming a threat to the settlers’ lives.

“We had no option but to cut and clear away the bushes to fix a small plastic tent when we arrived. Later, NGOs provided us with some materials to strengthen the tents, but the shelters are too small and the area is too congested,” said Huson Ahmed, 55, who lives in a 12-foot-by-22-foot tent with his family of nine. The Bangladesh government does not allow Ahmed and the other refugees to work, own bank accounts, or build semi-permanent or permanent houses. The refugees rely entirely on the support of the Bangladeshi government, as well as national and international aid organizations.

All the structures at the refugee camps are made of bamboo frames and plastic roofs, generally donated by national and international NGOs. According to the 2017 Emergency Market Mapping and Analysis (EMMA) report on the Rohingya Humanitarian Crisis, each Rohingya family settlement uses an average of 60 bamboo poles (weighing approximately 360 kg) to construct the temporary shelters.

Apart from shelter, the refugees depend on the forests for fuelwood. “Though there are LPG [liquefied petroleum gas] cylinders for cooking, they are not enough,” said Ahmed. An average of 6,800 tons (about 150 kg per family) of fuelwood is collected every month to satisfy fuel and shelter needs, according to the EMMA report.

With the sudden influx of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh in 2017, deforestation in Cox’s Bazar occurred rapidly. Teknaf and the adjoining Ukhiya are the worst affected due to their physical geography and a high concentration of camps.

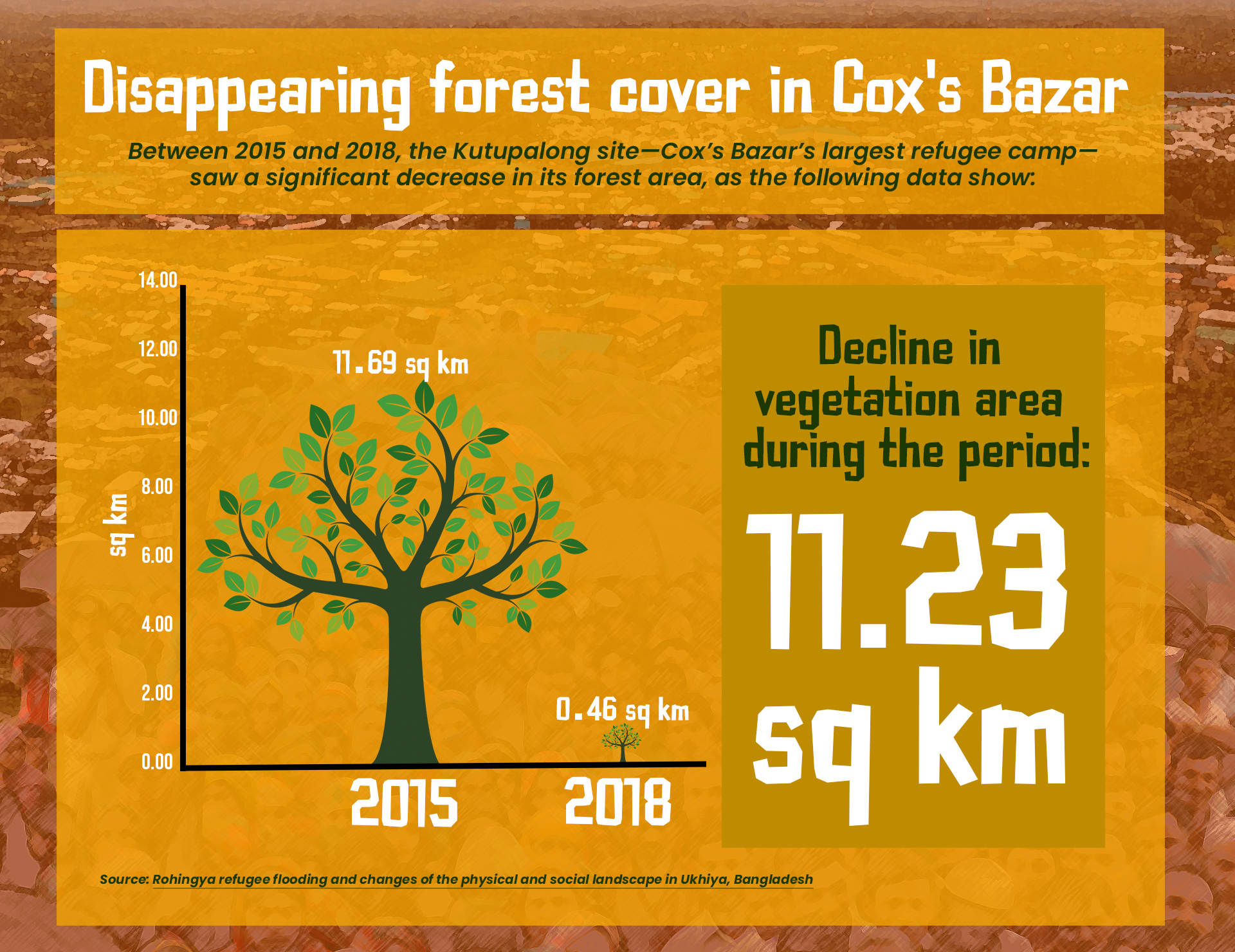

During the period 2015–2018, when over 74,000 refugees found shelter in the camps, the forest cover adjacent to the Kutupalong camp (Ukhiya sub-district) dropped from 11.69 sq km to 0.46 sq km—a significant decline in vegetation area of 11.23 sq km.

Given such deforestation, the increasing temperature is hardly a surprise.

Temperature rising

The impact of the refugee settlement on the climate became evident within a few years of establishment. Maximum temperature in the region has increased by 0.021 degrees Celsius every year due to the reduction in green cover, according to a 2015 study.

“We used to enjoy the shade of trees in the summer, but now temperatures are rising and there aren’t as many trees as there used to be,” said Nurul Kabir, 62, another Cox’s Bazar refugee. He also rued the squalid condition of his surroundings, adding, “We live in a very tightly packed settlement.”

Other activities, like cutting into the slopes to construct streets and stairways, are gradually raising the potential for landslides and inland floods in the camps.

“In the rainy season, the mud is washed away by the water. Shelters are destroyed and people die. Also, it’s difficult to stay inside the camp at night as we don’t have lights in these hilly areas,” explained Kabir. The Rohingya are mostly dependent on underground sources for water, which may cause land subsidence; and on forests for fuel, which increases the risk of landslides.

Worsening land quality becomes extremely hazardous for both hilly and coastal areas as it increases residents’ exposure to climate change impacts while decreasing community resilience and the capacity to adapt.

“The environmental injustice works in multifaceted ways. Apart from environmental degradation and bad living conditions, the high percentage of women and children at the camps are vulnerable and exposed to sexual harassment, malnutrition, and water- and vector-borne diseases,” said Mohammad Abdul Quader, associate professor and chairperson of the Department of Geography and Environment at Jagannath University, Bangladesh. Women and children compose 51 percent of the refugee camps’ population, he added.

Off to a remote island

In May 2020, the first coronavirus death in the refugee camps was reported. An already high concentration of people increased fear of uncontrollable transmission of the coronavirus. This prompted the government of Bangladesh to start moving the refugees to Bhasan Char, a remote and previously uninhabited silt island in the Bay of Bengal, which emerged from the sea only about two decades ago.

In 2018, the Bangladeshi government and its navy started building housing complexes, hospitals, schools, common kitchens, and playgrounds on Bhasan Char as a relocation site for Rohingya migrants. The government spent $350 million so that the formerly uninhabited island can host a million people.

COVID-19 spurred the resettlement of the migrants. An initial batch of 1,642 Rohingya was taken to Bhasan Char on December 4, 2020, followed by a second batch of 1,804 refugees a few weeks later.

International donors and organizations have decried the reported forced relocation of the Rohingya amid a dearth of knowledge and scientific data about the island’s safety. Despite government assurances that Bhasan Char—which means “floating island” in Bengali—is significantly better than the camps at Cox’s Bazar, it is vulnerable to cyclones.

“Against the will of people, many of the refugees were taken to the island for safety and security reasons. We are unsure of moving to a place where no other people have lived before,” said Tofail.

For him and the rest of the Rohingya in Bangladesh, living a life with dignity is still an elusive dream while statelessness remains an enormous burden. ●

Monika Mandal is an independent journalist who writes about sustainability and the environment. Follow her work on http://monikamondal.contently.com and find her on LinkedIn.com/In/nomnom/.