On January 23, 2020, just as the Chinese New Year celebrations were in full swing, the city of Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province in Central China, was cut off from the rest of the world.

The unprecedented decision to shut down the city at the center of the coronavirus outbreak was in response to a then-unnamed respiratory disease that was quickly making its way through the population, leaving weak, sick bodies in its wake. To contain the spread of the disease, the authorities sealed off the city from the rest of the country.

Wuhan residents were ordered to stay indoors. Medical personnel scrambled to attend to the sick. Provisions were uncertain, and so was the future. Overnight, a city that was ablaze with festivities turned into a ghost town. This was the nightmare faced by the Wuhan LGBT Center.

A scarcity of medication

For the most part, China remains intolerant of the LGBT community. For members of the community who have HIV/AIDS, this stigma can prove fatal.

The Wuhan LGBT Center hopes to help erase such stigma, improve the social conditions of the LGBT and HIV patients, and promote gender diversity. With the support of some 200 volunteers, the center conducts regular youth leadership training and educational campaigns and holds events, like Wuhan’s Pride Month and the Rainbow Gala, a talent show that helps raise funds for the organization.

The lockdown caught Xiaogang*, an employee at the center, by surprise. “After the lockdown of the city, our colleagues responsible for AIDS work began to receive a large number of requests for help from people living with AIDS,” they* said. “People were trapped in various places in the city and did not have enough medication on hand.” For people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV), skipping antiviral treatment could be life-threatening.

The lockdown caught Xiaogang*, an employee at the center, by surprise. “After the lockdown of the city, our colleagues responsible for AIDS work began to receive a large number of requests for help from people living with AIDS,” they* said. “People were trapped in various places in the city and did not have enough medication on hand.” For people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV), skipping antiviral treatment could be life-threatening.

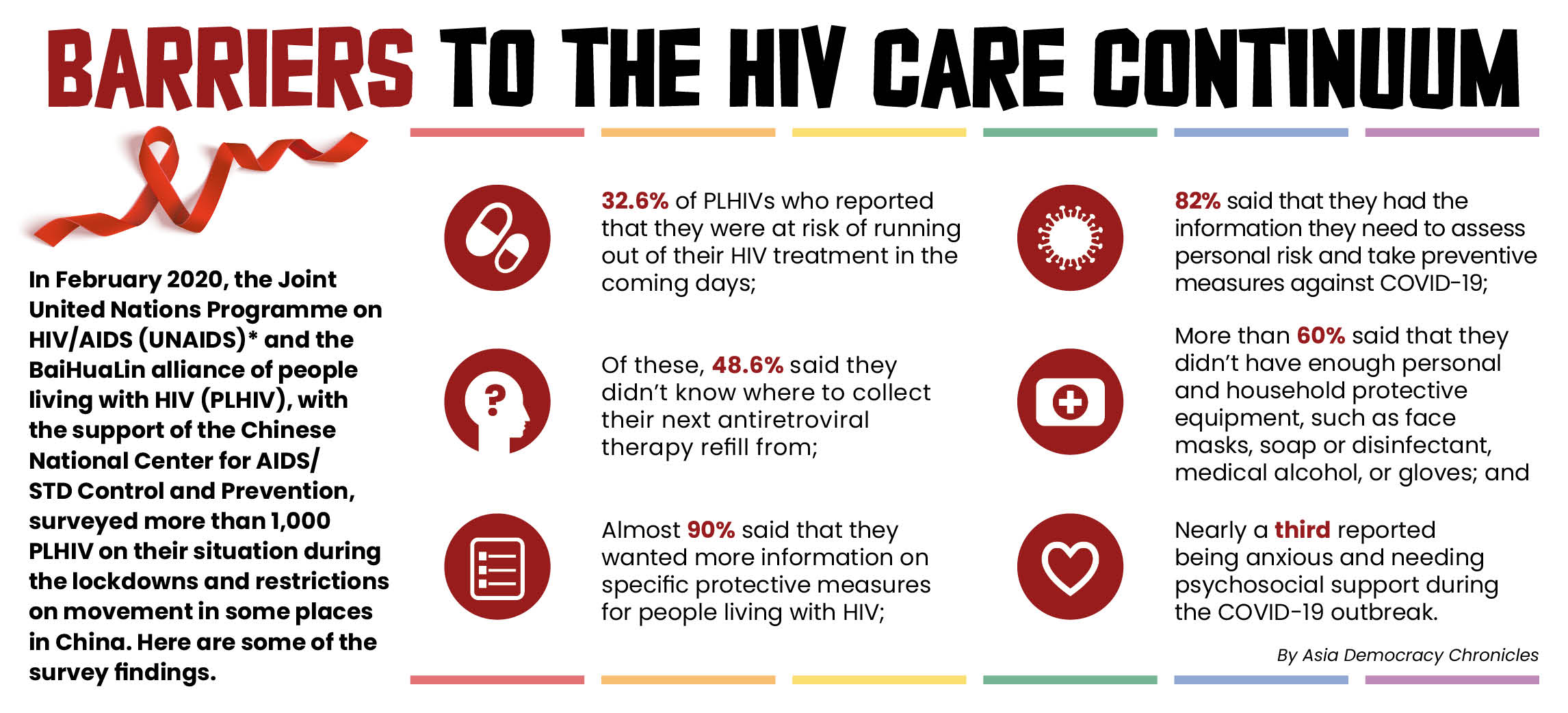

According to estimates from a joint report by the China Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), and the World Health Organization, about 1.25 million PLHIV lived in mainland China by the end of 2018.

As all transportation in Wuhan ground to a halt, the staff and volunteers packed and delivered the medicines to HIV patients who faced movement restrictions.

In the same year, nearly 20,000 PLHIV lived in Hubei province. This meant that the lockdown trapped thousands of patients in a place where their needed medication was in short supply.

Uneasy family relations

As a result of the lockdown, many roads were blocked and public transportation was suspended. Access to what little medicine was left became even more difficult. In some cases, patients had to call 110, China’s police hotline, to request escorts who could take them to centers to buy their medication. Some elderly PLHIV, facing language and technological barriers, had to walk long distances alone to fill their prescriptions at the hospitals that had stocks.

To make matters worse, the quarantine also forced many PLHIV back into their families’ houses. There, they risked the involuntary disclosure of their diagnoses. In fact, a few who developed fevers during the lockdown had to be isolated, and they were left with no choice but to reveal their HIV status to their families.

“Many patients would rather go off the drug than turn to their families,” Xiaogang said. “Their fear of disclosing their HIV status is much greater than their fear of losing their lives.”

As soon as the city was locked down, the Wuhan LGBT Center realized the gravity of the situation and immediately got to work. They first contacted the AIDS team at the Hubei Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) who, understanding how bad things could get, coordinated with local offices to exempt PLHIV from restriction orders when obtaining their medicines.

Wuhan LGBT Center staff and volunteers go to hospitals, request doctors to prescribe HIV medication, and pick up the lifesaving drugs.

As all transportation in Wuhan ground to a halt, the staff and volunteers packed and delivered the medicines to HIV patients who faced movement restrictions.

Grueling work

As a supplement, the center began disseminating to the LGBT community up-to-date information and policy changes on online platforms.

Ultimately, though, these measures would prove to be insufficient. As the requests for assistance from PLHIV surged, all of the center’s full-time staff, along with two volunteers, had to return to work. They often took 12-hour shifts on a daily basis and staggered their leaves so that services would continue uninterrupted.

Between January and May, the center was able to respond and provide phone counselling services to nearly 8,000 people. They also set up a convoy and medical support groups to pick up the medication and then returned to the Wuhan LGBT Center to package and mail the medication to the PLHIV. They also established a hotline, which was able to provide medication collection services to almost 3,000 PLHIV in lockdown.

*Source: UNAIDS

Since Wuhan was sealed off, the tiny team behind the Wuhan LGBT Center has been working fiercely and untiringly, trying to fill in where the local government could not, and fighting to keep the trapped PLHIV well. It was only in April, a month after the restrictions were lifted, that their workload started easing.

Now that Wuhan has returned to normal life, and the epidemic has been effectively controlled in China, Xiaogang says they cannot imagine what would have happened if they hadn’t been there to support the PLHIV during the lockdown

Civil society organizations like the Wuhan LGBT Center were able to make up for the government’s apparent lack of attention and action on PLHIV during the pandemic. The coronavirus outbreaks overwhelmed the health care system in China. As doctors in the AIDS units were deployed to care for the COVID-19 patients, there were not enough healthcare workers to respond to the large number of PLHIV seeking help.

Despite the center’s remarkable performance in supporting the PLHIV amid the pandemic, they continue to face many challenges. Programs and projects catering to these patients struggle to get off the ground; colleagues in the advocacy have gone on to different paths; funding has nearly dried up.

There is no rest for Xiaogang and their colleagues at the center. They are hunkering down and preparing for the next possible lockdown and keeping stock of whatever supplies they have leftover from the city’s first lockdown. The road ahead remains uncertain. ●

* For security reasons, Xiaogang’s real name is withheld, and the gender-neutral pronoun “they” is used.

Wu Yu-Hao is a social worker based in Hubei, China.