ahabia Khuzema is the leader of the Progressive Students Federation-Karachi, and she is one dissatisfied student. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Pakistan’s higher education commission issued an order for universities to conduct online classes in the country starting last June. However, Khuzema believes that the commission left all the burden resulting from such an order—of securing a computer, a reliable Internet connection, and a suitable space for study—to the students.

She said, “This is an added burden on the already strained pockets of the students because many parents and those students who support themselves have lost their jobs in the pandemic.” About 12.3 million to 18.5 million Pakistanis were laid off in the aftermath of a partial or complete shutdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “Moreover, with a terrible housing crisis in most of the urban centers, it is nearly impossible for working-class students to study at home,” Khuzema said.

A “nightmare” for female students

The haphazard conduct of online classes amid the COVID-19 crisis is an issue that greatly burdens the majority of students in Pakistan. However, female students from remote areas suffer the most hardships. Students living in the peripheries are hit hard, too.

For Khuzema’s female peers, the online classes have been “a nightmare,” said the student leader. “Before the pandemic, in a patriarchal society like ours where female education has never been considered important, many female students in Pakistan secretly went to college to study because their parents, spouses, or relatives would not allow them to seek an education,” she said. For such students, attending online classes during the lockdown is out of the question.

Yet even those female students whose parents allow them to study are also suffering, said Khuzema. “Most families are not taking online classes seriously and are burdening the female students with additional house chores.” Such a situation is common, said other interviewees for this report. The student leader added that domestic abuse has sharply increased during the pandemic, disproportionately affecting female students.

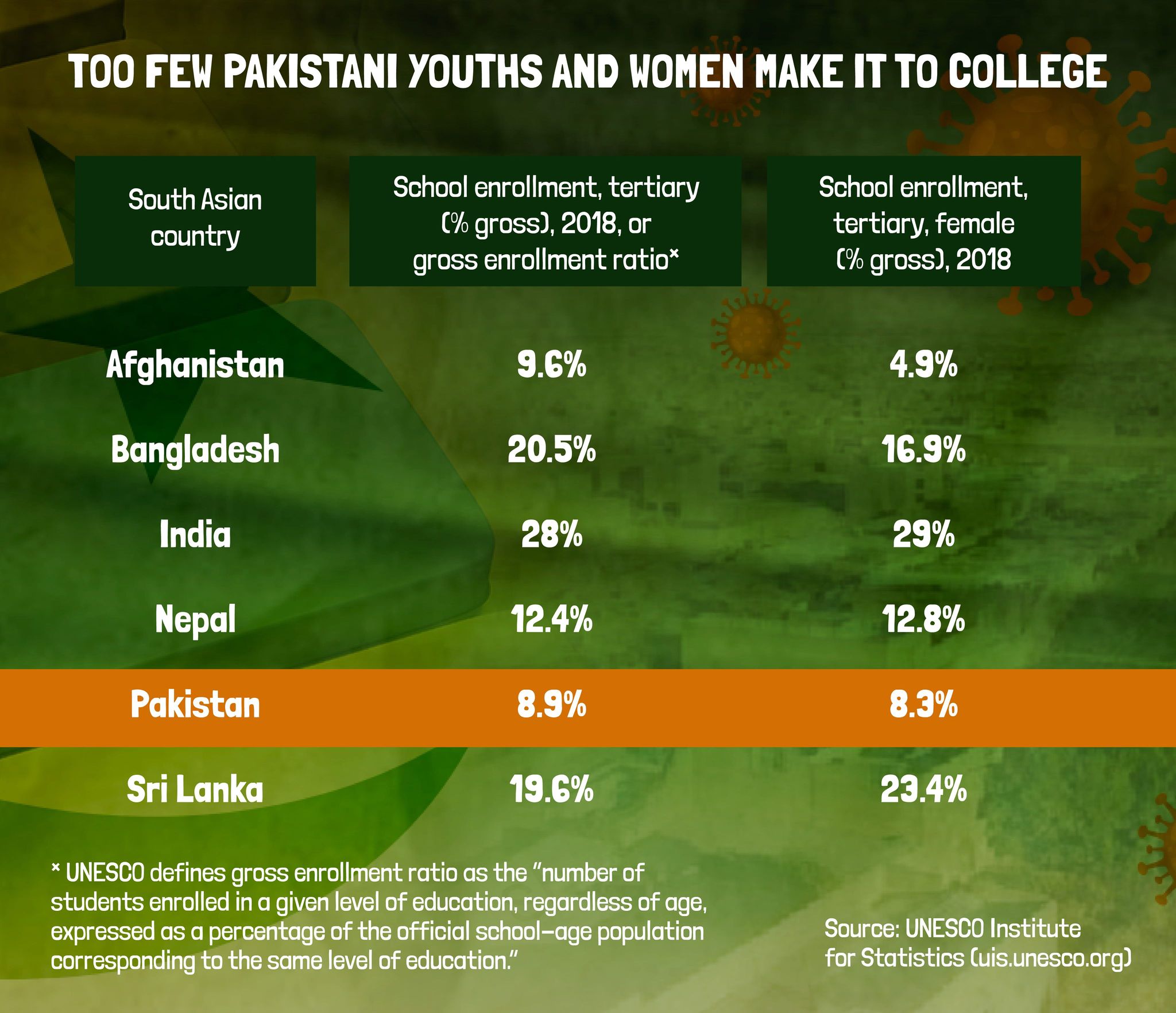

Khuzema is worried that the female students will bear the brunt of the economic slump. It is feared that dropout ratios will increase due to the lockdown-induced disruptions. She said: “We are living in times during which the majority of working-class students are most likely to drop out because of they will not be able to pay tuition fees. And it is the female students who will drop out first because in our society the education of sons is always prioritized over that of daughters.”

Hunting for Internet signals

The situation is grave for students living in Balochistan, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Gilgit-Baltistan, and Azad Kashmir. Many youths from these underdeveloped areas move to urban centers such as Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad; there are no good schools or employment opportunities in hometowns.

Now, in the aftermath of the pandemic and the closure of their schools, they had to return to their hometowns where they do not have access to the internet. As a result of the backwardness of their areas, they cannot attend online classes.

Majority of Balochistan’s population of 12.34 million have no access to the Internet, said Habib Kareem, a leader of the Baloch Students Organization. “More than half the people don’t even have smartphones.”

Balochistan is the poorest region in the country and has widespread unemployment. Its unemployment rate of 4.13% is the highest in Pakistan. Kareem said, “Out of 25,000 Baloch graduates, only 2,000 are able to secure jobs every year.”

The students in the region Gilgit-Baltistan also struggle with reliable access to the Internet. There is only one company, Special Communications Organization, that provides 3G and 4G services. “It is the military that runs this company,” said Haider Ali, the leader of Progressive Youth Alliance. “Its service is really bad.”

As a result, students in the region climb mountains and trek miles, hunting for elusive Internet signals, in order to attend their online classes. To make matters worse, they also suffer frequent power outages.

As university classes shift online, many students who lack computers, access to the Internet, and well-lit study areas are left behind. “There is no question of learning anything under these circumstances,” said Ali. He said that only a few universities have given students living in the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas and Gilgit-Baltistan extensions for submitting their assignments and have exempted them from taking online classes. “However, most students have had failing grades,” he said.

Khuzema and Ali’s concerns are shared by countless students who have mounted protests against online classes across the nation. Last June, in protests that took place in Quetta, the capital of Balochistan, the police arrested dozens of students, including women, who were demanding Internet access for online classes.

“Mediocre” online courses

The students who are leading these campaigns against online classes are speaking up against the uneven economic development in their country, which has left many towns outside the urban areas with spotty Internet access, scarce electricity, and scant opportunities for education and employment. According to them, there is no way out without challenging the economic system whose very basis is unequal ownership and distribution of wealth.

Altamash Tasadduq, a leader of Jammu Kashmir National Students Federation, said that online classes have been introduced in order to ensure that schools can continue to charge tuition fees. This is an injustice because the “quality of many online courses being offered currently is quite mediocre,” said the chairman of the higher education commission.

Tasadduq said that the state has no interest in catering to the needs and rights of the majority, and it is only interested in profits. “We are told that the state is supposed to be a mother to its citizens,” he said. “Then why is it that the state only cares for the education of a few rich and not the poor many? Even an uneducated mother wishes for all her children to be educated.” ●

Minerwa Tahir is a researcher and activist based in Karachi, Pakistan.