Sujit Tiwari traveled more than a thousand kilometers in a rented car with three friends in May, hoping to get home to Mahottari district in southern Nepal. The 26-year-old had been working in a car factory in Haryana, India, for the past two years.

In March 2020, when both India and Nepal announced national lockdowns in response to the COVID-19 crisis, Tiwari chose to stay in Haryana. He had hoped that when the lockdown was lifted, he could go back to work.

By May, however, Tiwari could no longer afford to pay his rent. So he decided to go home to Nepal with his three companions.

When Tiwari reached the town of Sursand in Bihar, near the Indian border with Nepal, he was tested for COVID-19 at the civil hospital there. He tested negative. Tiwari was confident that he would be allowed to enter Nepal. However, at the border, police officers told him that they had strict orders not to let anyone in.

Tiwari said in a phone interview, “I didn’t know what to do and was just waiting around at the border for three days.” He slept on the street. After three days, he was permitted to cross the border, but he needed to get tested again and stay in a government quarantine facility for 14 days.

On May 23, Tiwari went to the quarantine facility located in Jaleshwar’s Bakhari campus. At the public university, 150 to200 people who had crossed the border were staying at any given time. There were no beds, blankets, or any accommodations to speak of. Tiwari says that he slept on a bench in a classroom, next to another person.

On May 24, two people at the quarantine facility tested positive for COVID-19 and were transferred to a hospital. On May 26, Tiwari was again tested, and he was shocked to learn that he was positive for COVID-19. He had contracted the coronavirus at some point between his negative test in Sursand and his stay at the quarantine facility. At the facility, said Tiwari, “they didn’t sanitize or anything. We all shared one bathroom and one water pump.”

On May 24, two people at the quarantine facility tested positive for COVID-19 and were transferred to a hospital. On May 26, Tiwari was again tested, and he was shocked to learn that he was positive for COVID-19. He had contracted the coronavirus at some point between his negative test in Sursand and his stay at the quarantine facility. At the facility, said Tiwari, “they didn’t sanitize or anything. We all shared one bathroom and one water pump.”

Tiwari did not have any symptoms. After spending two weeks at the government hospital in Jaleshwar, he was allowed to go home in June. Tiwari finally arrived home on June 17, 2020.

Tiwari’s harrowing ordeal led him to decide that he was not going back to work in India anytime soon. “The experience of crossing the border was horrifying,” he said. “I’m not doing that again.”

Tiwari is one of an estimated 587,646 Nepali migrants who had been working in India before the COVID-19 crisis hit. Majority are represented in informal and seasonal work. The International Labour Organization estimates that 86% of these migrant workers are daily wage earners in the informal sector, primarily in agriculture and construction. They do not have formal employment contracts or other benefits, and their employers have no contractual obligations to provide them with food, accommodation, and health care. Another estimate suggests that two million Nepalis live and work in India.

![]()

The problems facing migrant returnees, particularly in southern Nepal, have been compounded by the floods and landslides that have killed many people and destroyed their homes and livelihoods.

![]()

When the lockdown was imposed in late March, the federal government had no working plan about how to repatriate these workers. As a result, thousands of Nepalis desperate to return home were stranded at the border without food, shelter, or any guidance about how they should proceed.

Some Nepalis swam across rivers to circumvent the authorities, while others staged protests. A report in The Kathmandu Post on March 31 quotes one Sunil Khanal of Malarani in Agrakhanchi as follows: “Yesterday, the security personnel started baton charging us and forced us back towards the Indian side of the border. But the Indian security force also stopped us from going back to India. We had no choice but to stage this sit-in in the no man’s land for our message to reach the authorities.”

On April 7, in response to two separate writ petitions filed by advocates Mina Khadka and Manish Kumar Shrestha, Nepal’s Supreme Court issued an interim order to the government to bring home all Nepali citizens stranded at the Indian border. The media still reported news about migrant returnees from India being forced to stay in no man’s lands without food and water at numerous border entry points as the lockdown continued to be extended.

On April 7, in response to two separate writ petitions filed by advocates Mina Khadka and Manish Kumar Shrestha, Nepal’s Supreme Court issued an interim order to the government to bring home all Nepali citizens stranded at the Indian border. The media still reported news about migrant returnees from India being forced to stay in no man’s lands without food and water at numerous border entry points as the lockdown continued to be extended.

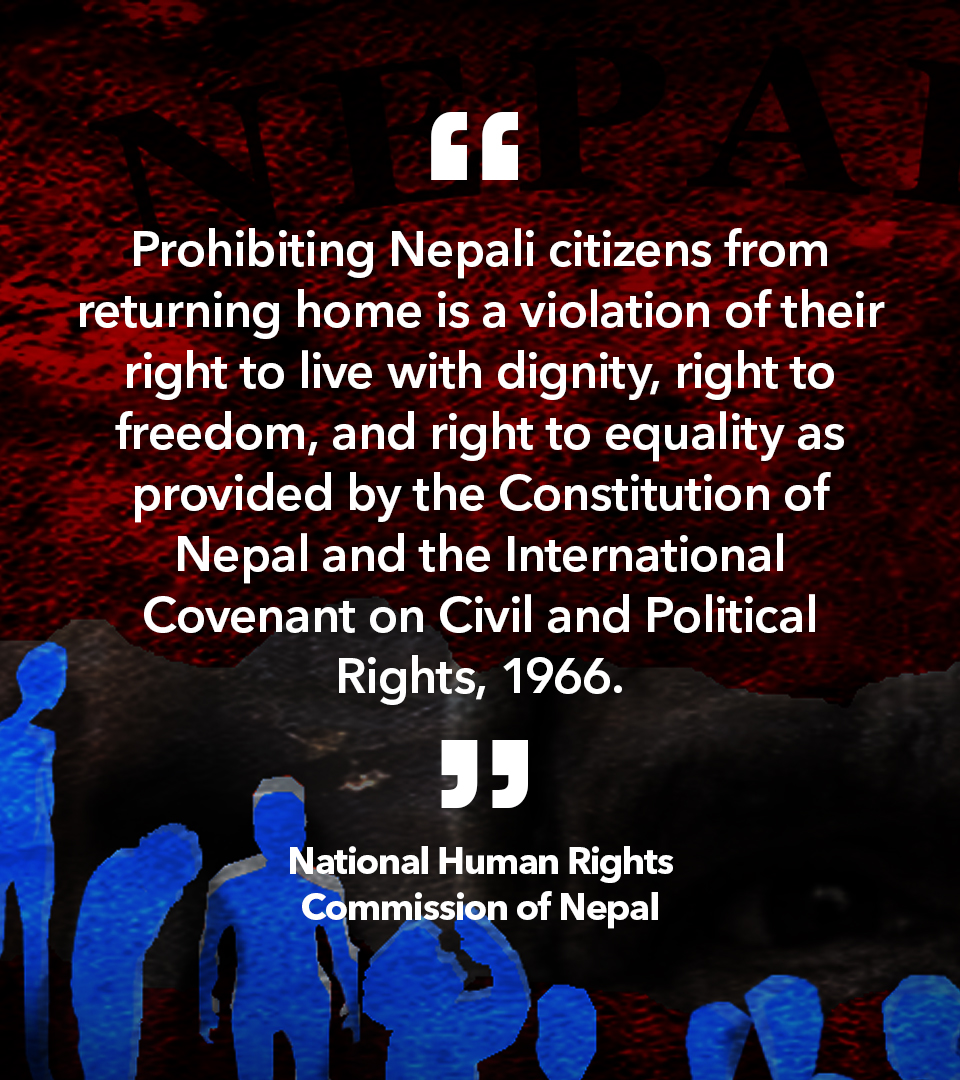

On May 11, the National Human Rights Commission of Nepal called attention to the inhumane treatment of the migrants at the border. In a statement, the commission said, “Prohibiting Nepali citizens from returning home is a violation of their right to live with dignity, right to freedom, and right to equality as provided by the Constitution of Nepal and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966.”

On June 3, more than two months after the first group of migrants from India started coming back to Nepal, the Embassy of Nepal in India issued a statement saying that 20 border points were going to be open for the migrants to enter. All those entering would be required to stay in government quarantine facilities for 14 days and get tested before proceeding to their respective municipalities. Many quarantine facilities are like the one that Tiwari lived in: makeshift, disorganized, devoid of resources, and dangerous.

In June, a woman who was staying at a quarantine facility in Kailali district was reportedly raped by three volunteers at the facility. In the same month, a teenage boy in Dhanusa district died at a provincial hospital while undergoing treatment for diarrhea. The teen was staying in a quarantine facility and reportedly got diarrhea from the unhygienic food provided in the facility.

Some humanitarian and non-governmental organizations have stepped in to fill the gaps left by the government’s failure to take care of the needs of migrants stranded at the border. Sano Paila, one such organization, provides food to migrant returnees at the Bhittamod border point where Tiwari entered Nepal.

According to Rahul Jha, a staff member at Sano Paila, the lack of clarity and coordination from the government has been appalling. Jha estimates that between 3,500 to 5,000 people have entered through Bhittamod since March. In a phone interview, he said, “From March to April, the police officers were telling us that they couldn’t let anyone enter because letting people in and out of the country is under federal government jurisdiction. The provincial government was not clear on what they wanted to do, and the lack of coordination was an absolute mess.”

Jha said that budgets had been allocated for feeding and sheltering the migrant returnees while they waited for their test results and were in quarantine. However, local government officials bemoaned the lack of manpower and resources, which made it necessary for non-government actors to step in. At the Bhittamod border point, some members of the military have also been involved in distributing food since June.

Nepal’s government eased lockdown restrictions on June 15. Since then, the numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths have continued to rise. As of September 9, 2020, there were 48,138 cumulative confirmed COVID-19 cases and 306 deaths in the country.

The government’s fumbled response to the crisis, of which the horrific treatment of migrant returnees is only one part, has led to widespread protests as the prime minister and members of the ruling party have been preoccupied with internal squabbles. On May 25, Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli even blamed migrant workers for spreading COVID-19, stating in a televised address that “people returning home from neighboring India have been flouting the rules and returning home while facing many difficulties to get across the border without proper tests.”

The problems facing migrant returnees, particularly in southern Nepal, have been compounded by the floods and landslides that have already killed many people and destroyed their homes and livelihoods. It is unclear how and when the travails of the migrant returnees will end. ●

Abha Lal is a journalist and editor based in Kathmandu who writes about human rights issues.