When the Indonesian government announced its first two COVID-19 cases in early March, Yoyo Yogasmana was unconcerned. “We never worry about anything that happens from outside the villages,” said the 50-year old farmer. “All of us work as usual.”

Yogasmana is a member of the Ciptagelar indigenous community. The 48,000-strong group of mostly farmers has been living in 568 villages in the Mount Halimun-Salak tropical rainforest since 1368. The 110,000-hectare national park is one of the largest forests left in Java, Indonesia’s most populous island.

Mount Halimun-Salak national park is located south of Indonesia’s capital Jakarta. It is one of the few conservation areas on the island of Java.

Since late March, in order to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, the Ciptagelar community has implemented a lockdown for people who live between 800 and 1,200 meters above sea level. “We literally never go outside the villages, so the policy is actually implemented for outsiders,” Yogasmana said. They also held traditional ceremonies to honor nature in the hope of receiving protection from the virus.

Now the Ciptagelar community faces another threat. In May, President Joko Widodo signed Presidential Regulation Number 66 of 2020, which states that the government can use land assets at the village level, including forests, for purposes deemed to be in the public interest and in keeping with the national strategic projects. The regulation was signed on May 19, 2020 and enacted the same day. It aims to speed up 89 major infrastructure projects billed as key to jump-starting the economy out of the pandemic-induced slump. These projects include nickel smelters and a rice estate spanning 900,000 hectares.

Indigenous rights’ defenders are concerned that the regulation does not explain how the government plans to avoid conflicts with the locals, who will bear the brunt of this newly minted policy. It also allows corporations to develop land, thereby exacerbating existing land conflicts.

A threat to self-sufficiency

Ciptagelar is a wealthy region that is self-sufficient in food. Hundreds of hectares of rice fields dominate the landscape, and the people grow vegetables and raise livestock. Yogasmana’s community never needs to buy food from outside the villages.

“We already have what we need, so we never worry about running out of food,” Yogasmana said. Ciptagelar has around 12,000 rice barns that, according to him, could feed his entire village for the next 95 years.

“We already have what we need, so we never worry about running out of food,” Yogasmana said. Ciptagelar has around 12,000 rice barns that, according to him, could feed his entire village for the next 95 years.

“The elders taught us never to sell rice because we believe that rice is the source of livelihood. And in times like this when chains of logistics are disrupted, the teaching makes sense.”

“For indigenous people, the forest means a way to survive,” said Rukka Sombolinggi, secretary general of the National Indigenous People Alliance. During the pandemic, the forests provide indigenous people with the food that the government may have failed to provide for them. “We can’t depend on the government,” said Sombolinggi. “And if the forests are gone, what do we do?”

Sombolinggi rues the enhanced power that the new regulation gives to the government and corporations to seize land from the locals, particularly the indigenous communities. “It shows that the regime has an exploitative bent,” she said in a statement. “The presidential regulation would only make it easier for the government to seize land.” She explained that as a food crisis looms on the horizon during the pandemic, food security is necessary and would only be possible if local communities could freely cultivate their land.

A recipe for worse land conflicts

In 1992, the Indonesian government designated Mount Halimun-Salak as a national park. The move drew criticism from the National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM), saying the Ciptagelar community was not consulted about the designation. Moreover, community members were also not recorded on the government’s database at that time. This lapse meant that the government could consider them illegal settlers in the national park.

Since then, reported tensions between the Ciptagelar indigenous people and the law enforcers have been frequent, according to the 2016 Komnas HAM report on the agrarian conflict. “The designation of the Halimun-Salak national park, without being communicated to the local people, has its own implications,” said the report.

Community members were forbidden to harvest produce such as timber, even for firewood, due to unclear forest borders. Ciptagelar indigenous people maintain a classification for the lands they occupy: leuweung titipan (mainly for ritual/ceremonies belonging to ancestors’ spirit); leuweung tutupan (protected land that is forbidden to use); and leuweung garapan (land for farming).

The presence of forest rangers around the national park also sparked fear among Ciptagelar indigenous communities. According to the report, “Many villagers were ‘caught red-handed’ and were mistakenly thought of as thieves, although most of the cases could be solved with dialogue.”

In 2015, the government launched an ambitious Agrarian Reform Land Objects and Complete Systematic Land Registration program that earmarked 12.7 million hectares of forests to be managed by communities through social forestry schemes. These include community forestry, village forests, community plantation forests, and customary forests. A total of 11.2 million land certificates were issued by the government in 2019, but corporations still held most of the land.

For years, agrarian conflicts between the government, corporations, and local people have brought about criminalization of farmers and deadly violence. Across Indonesia between 2015 and 2019, the Consortium for Agrarian Reform (CAR) recorded 55 deaths, 75 individuals shot, 757 wounded, and more than 1,200 arrests of individuals defending their land.

![]()

Across Indonesia between 2015 and 2019, the Consortium for Agrarian Reform recorded 55 deaths, 75 individuals shot, 757 wounded, and more than 1,200 arrests of individuals defending their land.

![]()

In March 2020, two farmers in South Sumatra were stabbed to death, allegedly by the security guards of an oil palm plantation company, PT Artha Prigel. However, investigations have yet to be concluded and the perpetrators brought to justice. The residents and the company have been in conflict for nearly three decades.

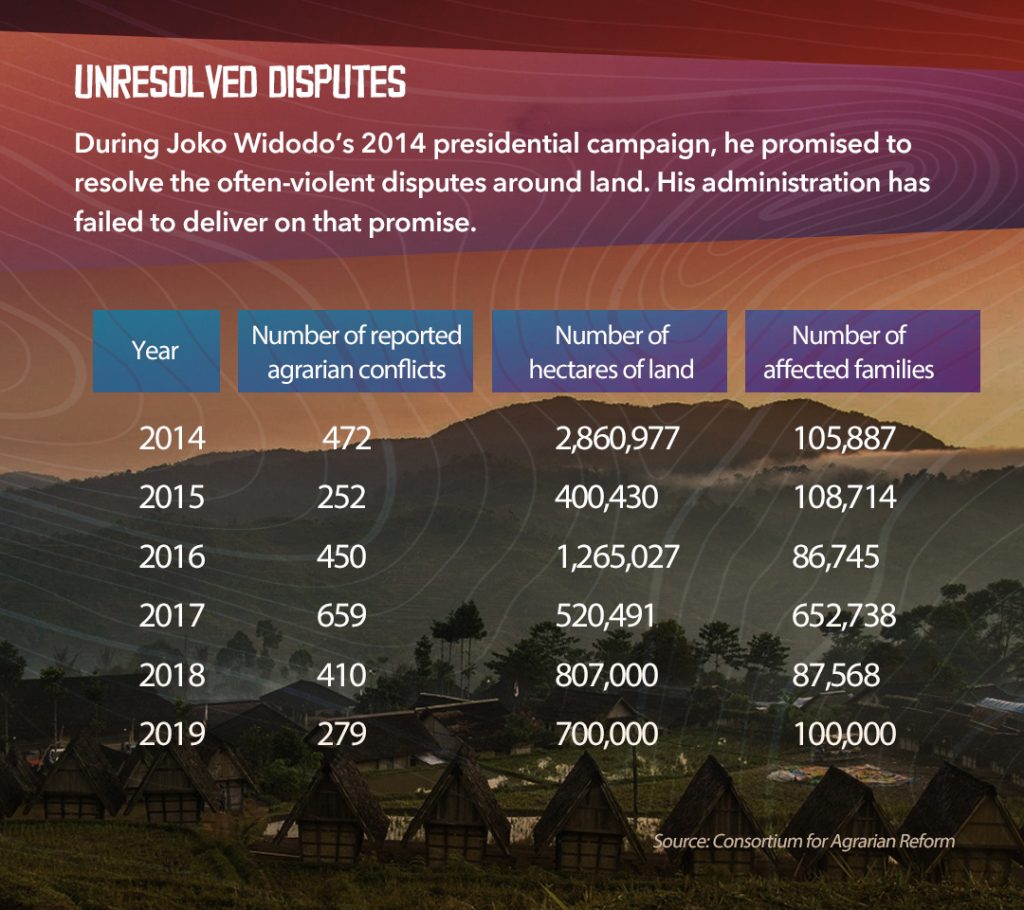

Meanwhile, CAR also recorded 279 agrarian conflicts in 2019 that involved more than 700,000 hectares of land and affected 100,000 families across the country. “This shows that even under Widodo’s administration, agrarian conflict has yet to be addressed despite his promise,” CAR campaigner Benny Wijaya said.

Sombolinggi of the National Indigenous People Alliance is concerned that the Presidential Regulation Number 66 will only worsen the current situation as the government asserts increased power to seize customary lands in conservative areas. This is expected to lead to the changing of borders and the resettlement of communities.

According to 2017 data provided by the National Indigenous People Alliance, a total of 1.62 million hectares of customary lands belongs to 609 indigenous communities within conservation areas. The regulation is therefore a threat to the existence of customary lands, according to Sombolinggi, and will eventually endanger the livelihood of indigenous people.

Indonesia has passed certain regulations — including a moratorium, a forest destruction prevention law, and a forestry law — to prevent land grabbing and protect the forests. However, these overlapping laws have consistently failed to serve their purpose. Greenpeace Indonesia’s analysis shows that deforestation is still rampant in the country and accounted for 2.5 million hectares out of 65.9 million hectares of forest under moratorium during the period 2002 to 2018.

CAR also recorded 50 farmers who have been arrested under the forest destruction prevention law between 2016 and 2020. “Some of the laws are discriminatory in nature,” Wijaya said. “Some of these were used to criminalize locals instead of prosecuting corporations.”

A contentious law

To make things worse, the House of Representatives is currently formulating the controversial Job Creation or Omnibus Law, which has triggered widespread criticism. The contentious Omnibus Law will grant land use rights to corporations for as long as 90 years.

The Omnibus Law has been met with strong opposition, particularly from activists and labor unions, who have dubbed the law pro-investor and adversarial to the workers’ welfare. Widespread mass protests have been reported nationwide since last year. Despite protests, the government said that the law will be passed in September this year.

“This is worse than during the colonial era,” CAR campaigner Wijaya said, adding that the government accorded only 75 years of land use rights to corporations. “This is truly a setback for Indonesia.”

Yogasmana is well aware that questionable government policies and legislation inimical to the interests of indigenous communities are largely to blame for their current predicament.

Yet, Ciptagelar will avoid conflicts at all costs, preferring to explore dialogue, he said. “We are just borrowing this land; it belongs to mother nature.”

Adi Rinaldi is a Jakarta-based freelance journalist. He was a staff writer at VICE Indonesia for four years, where he produced long-form journalism on topics including culture, the environment, and religious extremism. His byline has also appeared in New Naratif, Mongabay, and Coconuts.