On the afternoon of April 10, 2020, Indian authorities fetched Muslim student-activist Safoora Zargar, 27, from her home in south-east Delhi. She was brought to the police station to undergo interrogation on her involvement in the protests against the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act.

Enacted in 2019, the Act has been assailed by rights groups for legitimizing discrimination in India on the basis of religion.

After hours of interrogation, the police charged Zargar with violating the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act. She was also accused of being a “key conspirator” in February’s Delhi riots. She was arrested that evening.

Zargar was more than three months pregnant then. Despite her condition and the global COVID-19 pandemic, authorities still sent her to the overcrowded Tihar jail in New Delhi, a prison complex currently holding about 1.5 times its capacity, for detention. She was allowed to make a few short telephone calls but was denied of visitations and letters on account of COVID-19 restrictions.

Eventually, amid public outrage calling for Zargar’s release, the High Court granted her bail in April on “humanitarian grounds.”

While Zargar’s arrest has shown how governments can weaponize draconian policies — even during the pandemic — to silence dissent, it has also fueled discussions on women’s poor access to health in India’s prisons.

Female inmates, already distressed by the inability of family members to visit them and faced with an increased vulnerability to COVID-19 due to overcrowding, have to contend with the absence of healthcare professionals to attend to their needs, thus exacerbating their precarious condition.

Wanted: medical staff for women inmates

India’s women prisoners are often confined to small detention facilities within male prisons, with their basic needs — from sanitary pads to pre- and post-natal care for pregnant inmates — taking a backseat to those of the general prison population, Hindustan Times reported in 2017.

In the northern Indian state of Haryana, for instance, only one out of its 19 prisons has a hospital within the women’s correctional facility, the 2019 Inside Haryana Prisons report bared.

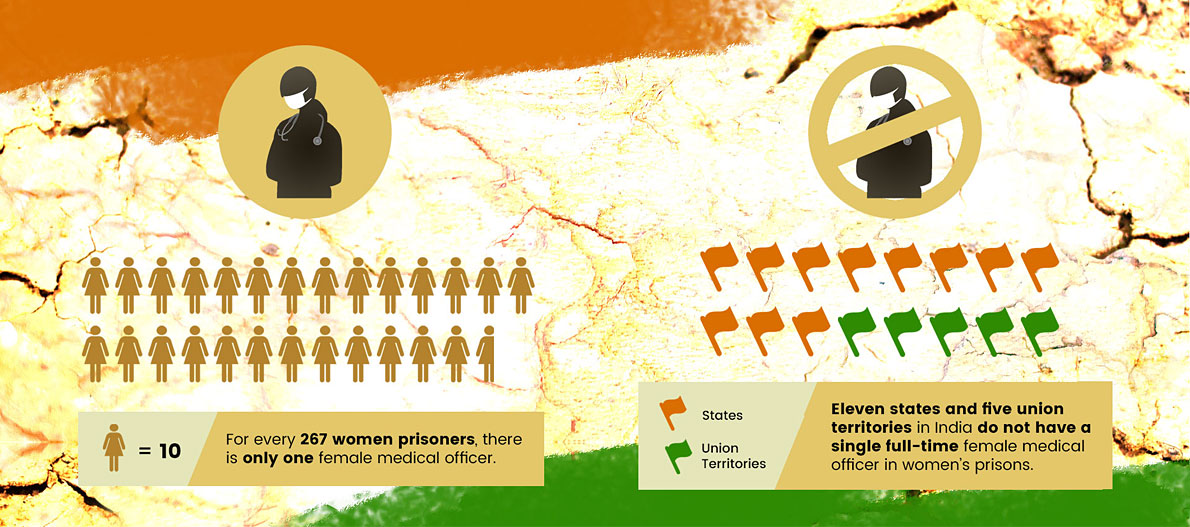

Adding to this is the huge shortage of female staff, ranging from wardens to doctors. Data from the 2018 Prison Statistics in India (PSI) show that there are only 72 female medical officers in the country. This translates to about one full-time female medical officer for every 267 women prisoners.

But even this is an oversimplification of the gruesome condition of the women inmates. Of the 29 states and seven union territories in the South Asian country, the PSI data showed that 11 states and five union territories lack a full-time female medical officer – a clear breach of national and international policies on prison administration.

These include the recommendations set by the 1987 National Expert Committee on Women Prisoners, which unanimously noted the “need for a female doctor on a full-time, part-time, or visiting/consulting basis to be available to every prison and custodial institution.” Most of its members also agreed that women prisoners would not be comfortable sharing their health concerns with or being examined by a male doctor.

More than three decades later, the 2018 Women in Prisons report of the Ministry of Women and Child Development reiterated the committee’s findings.

A similar recommendation is also stipulated in the Ministry of Home Affairs’ Model Prison Manual. The manual also stresses that medical facilities should be provided in women’s prisons, each of which should have at least one female gynecologist and psychiatrist. The manual was sent to all states and union territories in India for their guidance.

Internationally, Rule 25(1) of the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules) stipulates that every prison should have a healthcare service in place to ensure the physical and mental health of prisoners while paying special attention to prisoners with special healthcare needs.

Rule 10 (2) of the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders, commonly known as the Bangkok Rules, meanwhile, also requires that a woman physician or nurse should be made available if the woman prisoner requests that she be examined or treated by one.

The implementation of these standards by prison departments is spotty at best and poor at worst.

“Women inmates [in India] are never asked what they want,” Sabika Abbas, a project officer at the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative’s (CHRI), said. CHRI previously conducted a prison audit in Punjab and found that only a male doctor — the prison’s only physician — is available to examine the female patients. Worse, he routinely uses foul language, one female inmate shared.

“Rules and provisions are imposed on them and they have little say in the scheme of things,” Abbas explained.

The Ministry of Women and Child Development report recommended that prison administrations coordinate with local government physicians, including specialists like gynecologists and psychologists, to ensure that female doctors are present in prisons. In most of the prisons visited by CHRI in the north Indian states of Haryana and Punjab and in the southern state of Karnataka, the authorities had heeded the recommendation, with a female doctor from the district hospital now visiting the women’s prisons at regular intervals.

Disregarding safeguards

In 2006, a Supreme Court decision laid down the minimum standards to be observed in cases of pregnant women and children inside prisons.

These guidelines task authorities to ensure that minimum pre-natal and post-natal care for both the mother and child are available before a pregnant offender is sent to prison. Their dietary requirements must be met, too. Moreover, necessary arrangements should also be undertaken to allow pregnant inmates to deliver their babies outside of prison cells as much as possible.

These guidelines are aligned with the Nelson Mandela Rules and the Bangkok Rules.

In reality, however, this is not always the case. “While prisons routinely have specialists like dentists visiting, visits from gynecologists are less frequent,” said Sahana Manjesh, a consultant with CHRI.

Women inmates in India are generally allowed to keep their children with them until they are six years old. The provision applies to children below six years at the time of arrest, and not just to children born inside prisons. As of 2019, the PSI reported that 1,543 women prisoners were accompanied by at least one child, bringing the total number of children living inside the prisons to 1,779.

“Children, for none of their fault, but perforce, have to stay in jail with their mothers,” the Supreme Court decision read. “In some cases, it may be because of the tender age of the child, while in other cases, it may be because there is no one at home to look after them or to take care of them in absence of the mother. The jail environment [is] certainly not congenial for the development of the children.”

Despite the safeguards, a 2016 Amnesty International study documented cases of children being born inside prisons in Karnataka in complete disregard of the Supreme Court guidelines.

“Women prisoners with children have very little say in how they are treated,” the rights watchdog said. “And growing up in sub-standard prison conditions is far from conducive to a healthy childhood. Clearly, there’s a pressing need for the state government and the judiciary – and even civil society – to do much more.”

Limited options for mental health

As a measure to curb the spread of COVID-19, the prison departments of most states have stopped visits from the outside. Consequently, the number of doctors, lawyers, and organizations that used to provide support to the inmates and give them updates regarding their cases were also reduced.

Such visits were a crucial lifeline that safeguards the mental well-being of the inmates. Cutting their only means to connect with the outside world only puts them at greater risk of mental health problems.

Such visits were a crucial lifeline that safeguards the mental well-being of the inmates. Cutting their only means to connect with the outside world only puts them at greater risk of mental health problems.

To address such concerns, both the Bangkok Rules and the Model Prison Manual prescribe that “individualized, gender-sensitive, trauma-informed, and comprehensive mental health care and rehabilitation programs” should be made available to female inmates, especially those who experienced torture or sexual abuse or have underlying mental health issues.

A prison staff should be adequately trained to handle such situations, as well as identify signs of distress among inmates. However, CHRI found this ideal wanting, by and large, during its prison audit in Haryana and Punjab. The PSI report also showed that only eight states and union territories in India had appointed psychologists or psychiatrists in their prisons.

Haryana, for its part, has tried to address the issue by working with the director general of health services, who then directed the district mental health program teams consisting of clinical psychologists, psychiatric social workers, and community nurses to visit the district jail for two hours twice a week. Still, it is a temporary solution to a bigger problem.

As nations turn to hospitals and medical professionals to fight the pandemic, the need to deploy their counterparts inside prisons also became apparent. With most posts presently lying vacant, India’s prisons must act fast and fill them with the needed medical staff. ●

Anju Anna John is a project officer at Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative’s Prison Reforms Programme.