|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

J

ust as in other countries across the globe, being a member of the LGBTQI+ community in Mongolia can still expose one to harassment and physical assault. But the last few years has seen a seeming softening among many Mongolians — particularly the youth — toward LGBTQI+ people.

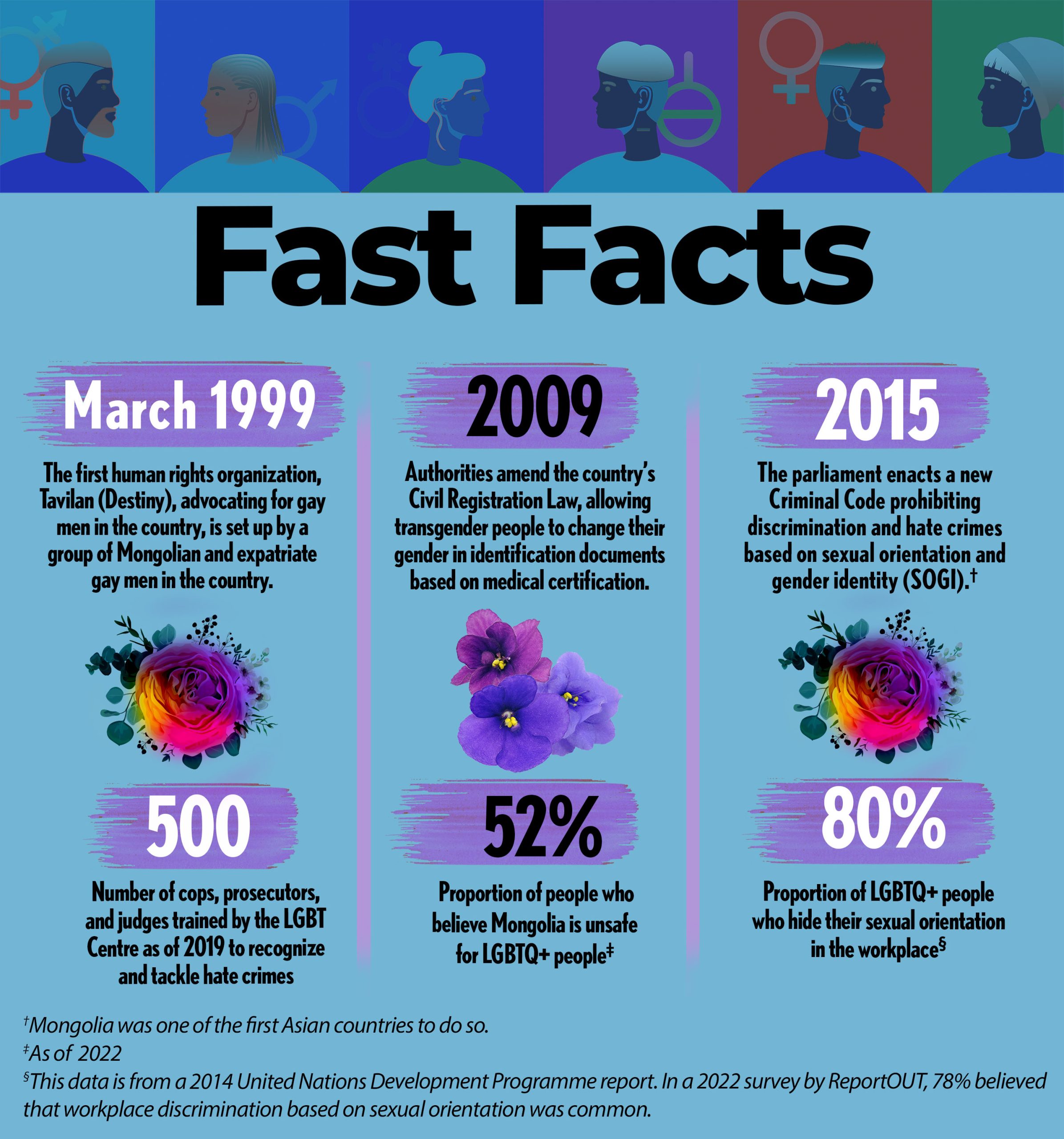

For instance, a 2021 study conducted by the private marketing research company Axon Neurolab found that 85.5 percent of Mongolian university students were not opposed to same-sex marriage, indicating a growing trend toward acceptance and tolerance of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities in the country. A 2019 baseline study by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) on gender equality in public administration also showed that public administrators’ understanding of gender rights had significantly increased, and gender rights, which were once seen as pertaining to women’s rights, have shifted to a broader scope.

It has probably helped that Mongolia has no institutional oppression toward LGBTQI+ people in the first place, and so activists have not been hedged against major oppressive institutions unlike in some other countries. But freedom of information, particularly from Western societies via television and social media, may have also contributed to this positive change, as has the work of the small but tireless non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia.

Since its inception in 2007, the LGBT Centre has been a major driving force in advocating for queer people’s rights not only in the public eye but also in the country’s legal framework. Its executive director Enkhmaa Enkhbold also says, though, “I can definitely say that, thanks to freedom of information, more Mongolians are starting to understand the rights of LGBTQI+ people, and that we are just people who want to live our lives normally and be accepted for who we are.”

Indeed, as late as 2014, a UNDP study noted that there had been little discussion of LGBTQI+ issues since Mongolia adopted its democratic constitution in 1992. And up until a few years ago, LGBTQI+ persons were portrayed unfavorably in Mongolian media. Practically all of the country’s media outlets presented people who were gay or non-conforming as misfits and sexual deviants, with the negative images including stereotyping and demonstrating a lack of sensitivity and little respect for privacy.

But as Mongolians became more exposed to Western media content, more locals began to appreciate LGBTQI+ rights. Psychologist Uulen Munkhbat, the LGBT Centre’s current youth coordinator, recounts, “When I was younger I use to watch TV shows like ‘Ellen’ with my mom, and she would explain to me who Ellen was and how she is very brave in being openly gay.”

Change at a crawl

For sure, Mongolia media have also been undergoing a slow transformation – especially after one of them suffered a stinging slap on the wrist. In 2015, the LGBT Centre itself became the first organization to file a complaint with the newly established Media Council of Mongolia, which was founded on the premise of the media needing a self-regulatory body to ensure ethical reporting. The complaint was about how a local major publication had used false and discriminatory narratives to portray LGBTQI+ people.

The Council ruled in favor of the LGBT Centre, and the publication had to retract the story and issue a public apology. Because it involved a well-known media outfit, the decision had a ripple effect. Since then, more media organizations have begun to attend the LGBT Centre’s press junkets, and more accurate reporting on LGBTQI+ persons has begun to increase in Mongolia. More and more LGBTQI+ people have also come out in public – some even in a big way. Among them are an openly queer person who has been podcasting since 2018, an androgynous-then-transgender model who has even starred in a movie, and an openly gay singer who has just released his first music video.

The change in attitude, however, has been gradual and is still a work in progress. There was a vicious backlash, for example, when a former executive director of the LGBT Centre said in a TV interview that almost 10 percent of Mongolia’s 3.3 million people belong to the LGBTQI+ community. In late 2019, a TV station teamed up with an ultranationalist group and forced — through threats of violence — a transgender sex worker to talk about her work on camera. The video was aired by the station and posted on the group’s Facebook page. Mongol police filed formal hate crime charges against the group’s leader, but no action was taken against the TV station.

The LGBT Centre’s Uulen confirms that there remains an overarching societal non-acceptance of LGBTQI+ people in Mongolia. While traditional Mongolian society is mainly indifferent toward LGBTQI+ people, the country’s small population and the insecurity that brings seem to be fueling much of the hostility toward those who do not fit into the binary gender framework. As Mongolia’s leaders push to increase the population, arguing this would provide better national security and a larger labor force to boost the economy, LGBTQI+ people appear to be an obstacle to that goal.

Hostility at home

Interestingly, many young LGBTQI+ in Mongolia face the harshest rejection from their families, and get beaten up and kicked out from their homes. Uulen says that she and her roommate have given temporary shelter to a few young people who had been driven out of their homes after they outed themselves to their parents. She adds that while her mother had once described U.S. comedian Ellen DeGeneres as “brave” for coming out as gay, her parents “weren’t as accepting toward me” when she came out as bisexual.

“It can be very disheartening to see the people who are supposed to protect and love you from the societal negativities are the ones who hurt you the most,” says Uulen, who clarifies that her family still seems to care for her even though they avoid talking about her sexual orientation. “But I think things are getting better with each day. We get calls more from family members seeking advice about their children.”

The LGBT Centre, in fact, has been a big player in bringing about positive attitudinal changes among Mongolians toward LGBTQI+ people. The Centre has been an active participant in advocating for and attempting to advance the rights of queer people in criminal and labor settings.

Some of its efforts have paid off; in 2017, Mongolia passed a law prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. This legislation marked a milestone for the country’s LGBTQI+ community, as it was the first time the government had officially recognized and protected the rights of LGBTQI+ individuals, as well as mandated gender-sensitivity training for members of Mongolia’s police force.

Since 2014, the Centre has also served as a bulwark for the Mongolian Pride Parades. Former LGBT Centre activists recall how difficult it had been at first to obtain official permission just to march down the streets of Ulaanbaatar, and how most of the time they would be forced to take streets with very little public visibility. According to the activists, barely 20 people would take part in the march during the early years. By 2019, however, the Pride Parade had more than 200 participants, including non-LGBTQI+ who wanted to show their solidarity with the community.

Still lacking understanding

Two years later, the LGBT Centre held its largest pride and equality celebration yet, with posters and banners on buses throughout Ulaanbaatar advocating for the rights of LGBTQI+ people, as well as those who had been marginalized by society due to their age and disability. When the head of the capital city’s road and transportation projects ordered the removal of all banners from buses, civil-society organizations, and the media joined the Centre in denouncing him as a government official with no regard for human rights.

Comments the Centre’s head Enkhmaa: “Even though there is societal change, the hardest thing we face is lawmakers and government officials who claim to understand the fundamentals of human rights but have little understanding of gender sensitivity toward queer people.”

Other rights advocates say that most of Mongolia’s current laws that protect human rights are in place only because they were a way to draw in Western support. They say that the legislators sign on to these laws and even international conventions without really looking into what these are all about, just so Mongolia can reap the economic benefits. This is why, rights advocates say, while Mongolian laws allow a transperson to change their gender on legal documents, they face a lot of discrimination once they try to do so at public-service institutions. To rights advocates, this only indicates how the system isn’t really trying to protect the rights of trans people.

Enkhmaa says,”I believe we can make significant progress if our leaders, or even half of our legislators, recognize who we are and advocate for the rights of queer people.”

She observes that while there is no explicit law in Mongolia prohibiting same-sex marriage, there is no legal framework in place to recognize or protect the rights of same-sex couples. As a result, says Enkhmaa, same-sex couples cannot enjoy the same legal protections and benefits as opposite-sex couples do.

“Perhaps one day Mongolia will pass legislation recognizing same-sex marriage,” she says. “If that happens, I see a lot of benefits for not only LGBTQI+ rights but also advancing human rights and democracy in Mongolia.”◉