|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

L

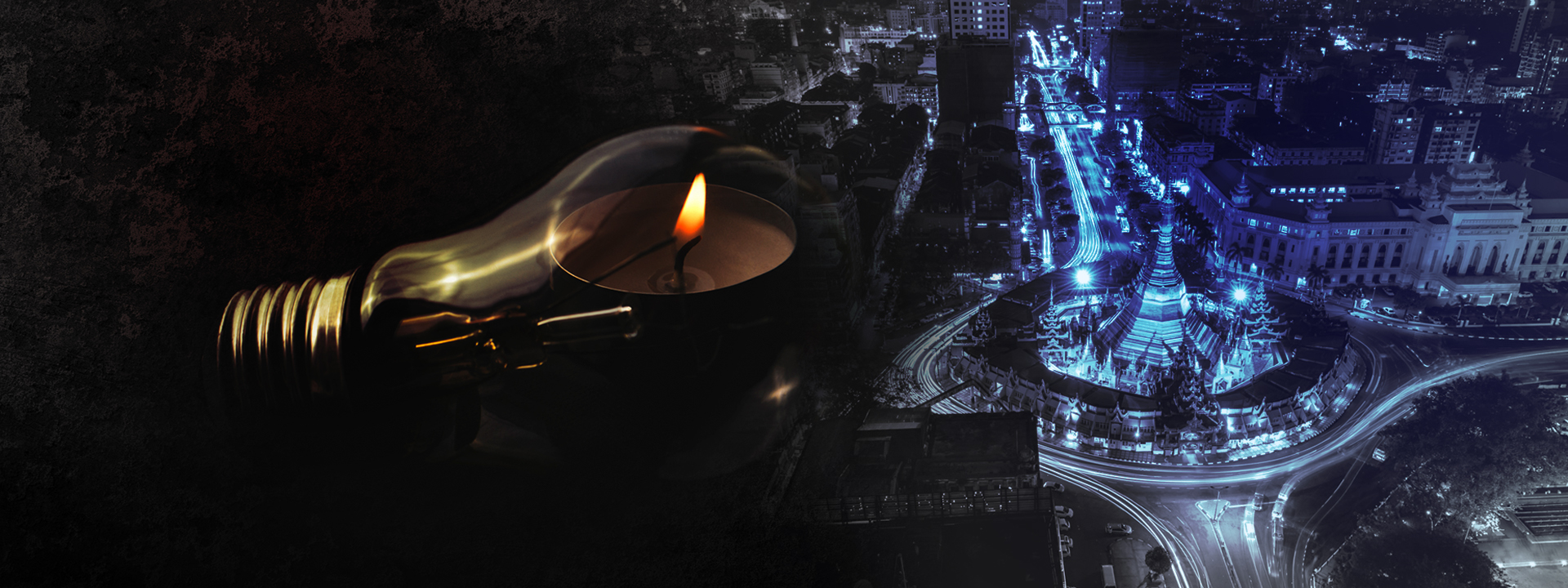

ike any other commercial capital in the world, Yangon has always been a 24-hour metropolis, with its businesses ranging from seaport trading and manufacturing to entertainment services and restaurants and teashops humming with activity day and night.

Yet since last year, many of those activities have slowed down. In fact, some of them have stopped altogether as businesses and factories shut down in the face of longer and more frequent power outages, exacerbating Myanmar’s debilitating economic crisis.

“We can’t do anything when power is off,” says a small-scale business owner in Yangon’s Bahan Township. “We have to stop the business. So, our business doesn’t go well like in the past. All business owners who rely on electric power face similar problems.”

“It affects all our works,” says the business owner whose family makes rubber stamps. “We need Internet at our workplace. We also have to save our phone battery and use it only when necessary. When we can’t cook as the power is cut, we have to eat outside and that cost more. So, expense for food increase almost every day.”

Another businessman says that he bought a diesel generator just to keep his enterprise running. But he says that some factories, especially those in the garment sector, have shut down completely since March last year due to the power outages. Last October, the Federation of General Workers Myanmar announced that nearly 200 factories and industries in the Yangon region had submitted documents needed for their permanent closure this year.

A labor activist points out that this may only lead to more joblessness; as it is, the International Labor Organization says that Myanmar now has 1.6 million people unemployed, among whom more than 300,000 are garment industry workers.

Fewer players, unpaid bills

Already hit by international sanctions because of the February 2021 coup and the military’s continuing rights violations, Myanmar’s junta has been having difficulty in keeping the country’s economy on even keel as investors and companies from overseas pull out one after the other. Even Chinese state-owned enterprises have supposedly been discouraged by Beijing from getting involved in Myanmar, among them those in the crucial energy sector, according to a report by Nikkei Asia.

This may partly explain why, since early 2022, Yangon and most of the rest of Myanmar have been having rolling blackouts that last for hours on end. Yet, state media have quoted the ruling junta’s spokesperson, Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun, as saying that increased prices for natural gas used for generating plants, maintenance, and upgrades at the Yadana offshore gas project, and opposition forces’ attacks on transmission towers in Kayah state are among the reasons for the power outages.

Pro-democracy advocates meanwhile say that the power outages are a junta strategy, and are aimed to make the life of members of the Civil Disobedience Movement and individuals who oppose the military rule more difficult. Indeed, activists note that while residents in Yangon, Mandalay, and other major cities suffer from power outages, military officials who live in Naypyidaw, the country’s official capital, have enjoyed uninterrupted electricity since the February 2021 coup.

Sources: Radio Free Asia, Nikkei Asia, Voice of America, International Trade Administration, Fulcrum

But a power industry analyst based in Naypyidaw says that problems encountered by supplier VPower have greatly affected power stations operation in the country, leading to the frequent power outage across Myanmar today.

He adds that the government led by the National League for Democracy (NLD) had invited bids from the Hong Kong-listed VPower Group and its partner China National Technical Import and Export Corp. in 2019 to address electricity shortage in Burma, especially during summer. Hydropower plants, which are the country’s main source of energy, cannot run at full capacity during the summer.

Just months after the coup, however, the VPower Group announced that it had pulled out two of its nine power station projects in Myanmar, adding that it would not be renewing the contracts for the stations in Rakhine State and Myingyan Township in Mandalay region. The company said that the decision came after it faced “challenging times” amid the economic turmoil caused by the military’s power grab. A September 2022 report by the online Frontier Myanmar also said that a leaked document indicated that two more of VPower projects in the country had been suspended.

An official from the Electric Power Corporation (EPC), who asks not to be named, says that at least for the Yangon region, the power outage arose because the military government no longer buys gas from VPower. He adds that the current situation will only get worse from this point forward. In truth, March marks the beginning of summer in Myanmar, which means power demand will shoot up as temperatures rise.

“During the NLD government, we distributed electric power to all townships in Yangon region,” says the EPC official. “Yangon’s electricity supply is 50 percent of the whole country’s. And that electric power came from LNG [liquified natural gas] from VPower. But the State Administration Council [the official governing body of the military regime] stopped buying LNG from VPower since early October 2021. We can’t operate all power stations in Yangon region.”

Hours-long power cuts

NLD, headed by Nobel Peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, won the 2020 elections by another landslide. But the winners were unable to take their oaths of office because of the coup. Daw Suu Kyi is now in prison on trumped-up charges of corruption along with several other NLD officials. Many other party leaders and members are either in exile, on the run, or dead.

Some Yangon residents recall that before the NLD administration gained power in 2016, there had also been occasional outages under the government led by former General U Thein Sein. But, they say, these were not as bad as what has been happening under the current junta.

Others say that during the civilian government under Daw Suu Kyi’s leadership, electricity was cut only when a transformer bogged down or whenever maintenance service was performed. Nowadays, they say, authorities don’t even take much action to restore power and even ignore complaints by Yangon residents.

“They don’t take any responsibility,” says the maker of rubber stamps, referring to the junta. “We can’t predict when the power is coming and when it will be cut. And we don’t know how long it will last, too.”

Supposedly, though, Yangon’s power outages are conducted on rotation twice a day, and lasts for six hours each time (or a total of 12 hours per day). In Monywa city, in northwestern Myanmar’s Sagaing region, the outages occurs twice a day for three hours at a time. Monywa residents have stockpiled batteries and power inverters, according to some of the residents. In Mon State in southern Myanmar, some factory owners have turned to generators keep their businesses going.

In Amarapura township, Mandalay region, electricity is available for only eight hours each day, according to local residents. That is also the case in Mandalay city, where a textile-factory owner says that power comes at eight in the morning and is cut at noon. It resumes four hours later, but is turned off again at eight p.m.

“We have to spend more money to buy gas and charcoal and use them when power is off,” says the factory owner. “EPC staff never explain why the power is off. We suffer badly under unpredictable power distribution. It is a crisis for us.”

“I want swear at junta chief Min Aung Hlaing for all of these consequences,” says the infuriated business owner. “I didn’t experience such bad things during the civilian government.”

She says that under the NLD government, power outages didn’t really last long. But she says that under the current junta, “ no one is even taking responsibility for the power cut.”

“We don’t know who and where to complain,” she says. “Electricity unit price increase regularly even though electricity power is cut irresponsibly.” (Under the NLD government, one unit of power was MMK 120 or US$0.057. Today it is MMK 300 or US$0.14.)

For now, most people are gritting their teeth and trying to cope with the intermittent power service. People have turned to firewood and charcoal to cook meals. At night, wet-market vendors and homeowners alike use candles and homemade lamps for lighting. Doing the laundry is postponed until the electricity is turned back on — which can sometimes mean in the wee hours of the morning in some areas.

“We can’t prepare lunch boxes to take to the office as we can’t cook in the morning,” says one writer who lives in Bahan Township in Yangon. “I use a laptop for writing, and I need electric power to charge my laptop’s battery. Whenever I complain to EPC about the outage, they say that they will work on it. But the electric power never comes back.”◉