|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

M

ore than three years after it was given an official go-signal, a planned high court complex inside a conservation area in Jammu in northern India has yet to have even the groundbreaking done. But those opposed to the plan say that they will remain vigilant, given the lack of any signal that what has been described as one of the “lungs of Jammu” is no longer under threat.

In fact, some activists are now using the issue of what they deem to be a misplaced court complex to raise awareness on climate change and the importance of forests to everyday living.

“The Raika issue started a fight, which was neglected due to politics,” says Anmol Ohri, founder of the non-profit Climate Front Jammu. “We want the Raika Movement to make history and tell people how important it is to save trees. We will not leave any stone unturned to save Raika.”

“We have launched an agitation against this environmentally disastrous plan of the government,” says Ishwar Das Khajuria, another activist. “If they won’t change their decision, we will start a nationwide movement to raise awareness about the Raika forest.”

He says that the whole world is battling with the climate crisis right now, but the administration in Jammu is not learning any lesson from this at all. Asserts Khajuria: “Cutting down 38,000 trees in Raika forest will ultimately create environmental destruction in the region. I call this an unfair decision by the government.”

Facts and fallacies

Raika forest is located within the Bahu Conservation Reserve on the outskirts of Jammu City, and lies along the River Tawi. There is a community of Gujjar (an indigenous group) that lives in the forest, while less than four kms away from the reserve is the Ramnagar Wildlife Sanctuary. Established in 1981, the reserve covers some 19 sq kms.

In 2019, the Law, Parliamentary, and Justice Affairs of Jammu and Kashmir (J & K) proposed shifting the J & K High Court (Jammu wing) from its existing complex in Janipur to Raika. The intent was issued to the Forest Department and the whole case was processed under provisions of the now-repealed J&K Forest Conservation Act.

Ohri, who began the ‘Save the Raika Forest Movement’ last year, echoes other activists in saying that the project suffers from certain legal infirmities and fallacies. For one, notes Ohri, Section 2(2) of the Act restricts the use of forest land for non-forest purposes to not more than five hectares. Yet the High Court acquired approximately 40 hectares of forest land for its proposed new complex. For another, the project’s approval had stipulated that only 3,000 trees would be felled. But the number that has been touted about for more than three years now is 38,006.

Documents regarding the plan also say that some 22 Gujjar households will be affected by the High Court’s move to Raika. Ohri, though, says that there are at least 50 households in the area where the new complex will be built; they are all bound to be displaced, despite having lived in Raika for generations and having – according to Ohri – “100 years of old ‘Girdoriya’ land records.” Raika also has at some 150 species of trees and shrubs, as well as a wide range of wildlife, including peacocks, foxes, porcupines, leopards, and the endangered musk deer.

Losing more than trees

India actually has laws aimed at preventing deforestation, including a ban on cutting trees without government-committee approvals. According to forest data aggregator Global Forest Watch (GFW), this has helped limit large-scale deforestation in the country. GFW also says, however: “(There) is immense pressure on forests due to developmental needs of the country. Diversion of forest lands for development purposes, such as industrialization, roads and irrigation projects has led to much forest loss. Since 1980, India has diverted 1.5 million hectares of forest land for development and a majority of this loss occurred since 2000.”

“Forest loss impacts India’s carbon emissions,” GFW says. “FSI estimates show that India has a carbon stock of 7.1 gigatons that has been increasing over the years with net tree cover gain. According to GFW, loss of tree cover in India releases an average of 0.037 gigatons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere per year. This is equivalent to emissions produced by the consumption of four billion gallons of gasoline. The increase in stock means that the carbon loss is compensated for by carbon sequestration, but further reduced deforestation could make India’s forests a larger carbon sink.”

In Jammu, Ohri argues that the loss of thousands of trees in Raika can only contribute to soil erosion and increase the likelihood of floods. Khajuria meanwhile says that the “administration in Jammu,” seems to want to “create another Josimath,” referring to a town in Uttarakhand state that is sinking under the weight of overdevelopment, as well as because of the effects of climate change.

Khajuria says that the High Court complex plan in Raika is the “worst” government project yet and will “badly affect the ecological imbalance in the region.”

Professor A.S. Jasrotia, who heads of the Department of Remote Sensing and GIS of the University of Jammu, for his part says that shifting the old high court complex is the need of the hour for the benefit of people and government officials. But he also says that the government should think twice before cutting down 38,000 trees, which he thinks will lead to “environmental disaster.”

Complex consequences

This is not the first time the J & K High Court took over forest land. More than two decades ago, it built its present complex in Ramnagar Rakh, which used to have some 30 sq kms of forest; today it has around five sq kms.

Among the reasons cited for the impending move to Raika is that the current complex is old and in disrepair. The present site is said to be plagued by traffic jams as well. But this only underlines a devastating consequence of building a High Court complex in Raika: having such an institution there is likely to attract more development to the area, which would include businesses catering to the daily needs of court-goers and staff.

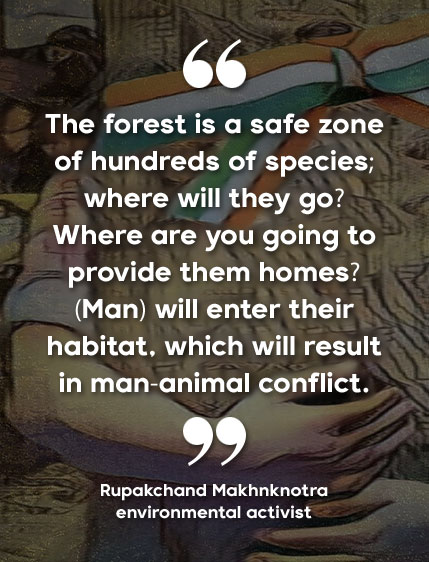

Increased human activity in the area can also lead to further encroachment into Raika and disturb forest life all the more. It is not farfetched to predict an increase in human-animal conflict as well; in the last few years, there have already been leopard attacks in urban areas in Jammu and Kashmir.

“The forest is a safe zone of hundreds of species, where will they go?” asks social and environmental activist Rupakchand Makhnknotra. “Where are you going to provide them homes? (Man) will enter their habitat, which will result in man-animal conflict.”

According to Makhnknotra, people by and large want to express their resentment against this initiative, but are apprehensive about being booked under the Public Safety Act. Young activists from Jammu, though, are bent on continuing to educate the public about the project by participating in marches, visiting schools and universities, and frequently posting on social media.

That the J & K High Court has yet to start construction on its planned complex in Raika has been attributed by some to the usual bureaucratic inefficiency and red tape – which would be ironic, considering the apparent haste with which it acquired approval for the project. The pandemic has also obviously had a lot to do with the delay.

Other observers, however, say that the opposition put up by activists has contributed in putting the magistrates and local authorities in a prolonged pause.

There is still no telling whether that will eventually lead to a full stop to the plan.”◉