|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

H

ideko Hakamata has been waiting for more than half a century for justice. Now 90 years old, she is fighting for the freedom of her brother Iwao who was handed the death penalty in 1968. This 13 March, the Tokyo High Court is expected to rule on a retrial case Hideko filed on Iwao’s behalf.

Iwao, 86, was convicted of the murder of a family of four. He was temporarily released in 2014 after being granted a retrial based on fresh DNA evidence that overturned the previous guilty verdict. By then he had already spent 46 years on Death Row. He now resides at Hideko’s home, but prosecutors have continued to demand capital punishment for Iwao and had appealed against his retrial.

According to Hideko, her brother has been suffering from bouts of severe delusion — shivering uncontrollably when he sees men and at times even washing his rice, fearing the food is poisoned.

“My brother succumbed to severe psychological pressure as he waited for years for that knock on the door by prison wardens to take him to the execution chamber,” Hideko tells ADC in an interview. Prisoners on death row in Japan are told of their execution in the morning of the day they are hanged a few hours later. after the notification. The government has justified such short notice as providing the inmate emotional stability before death, but critics say it actually has the opposite effect. The inmate’s family members and lawyers are also informed of the execution only after it is carried out.

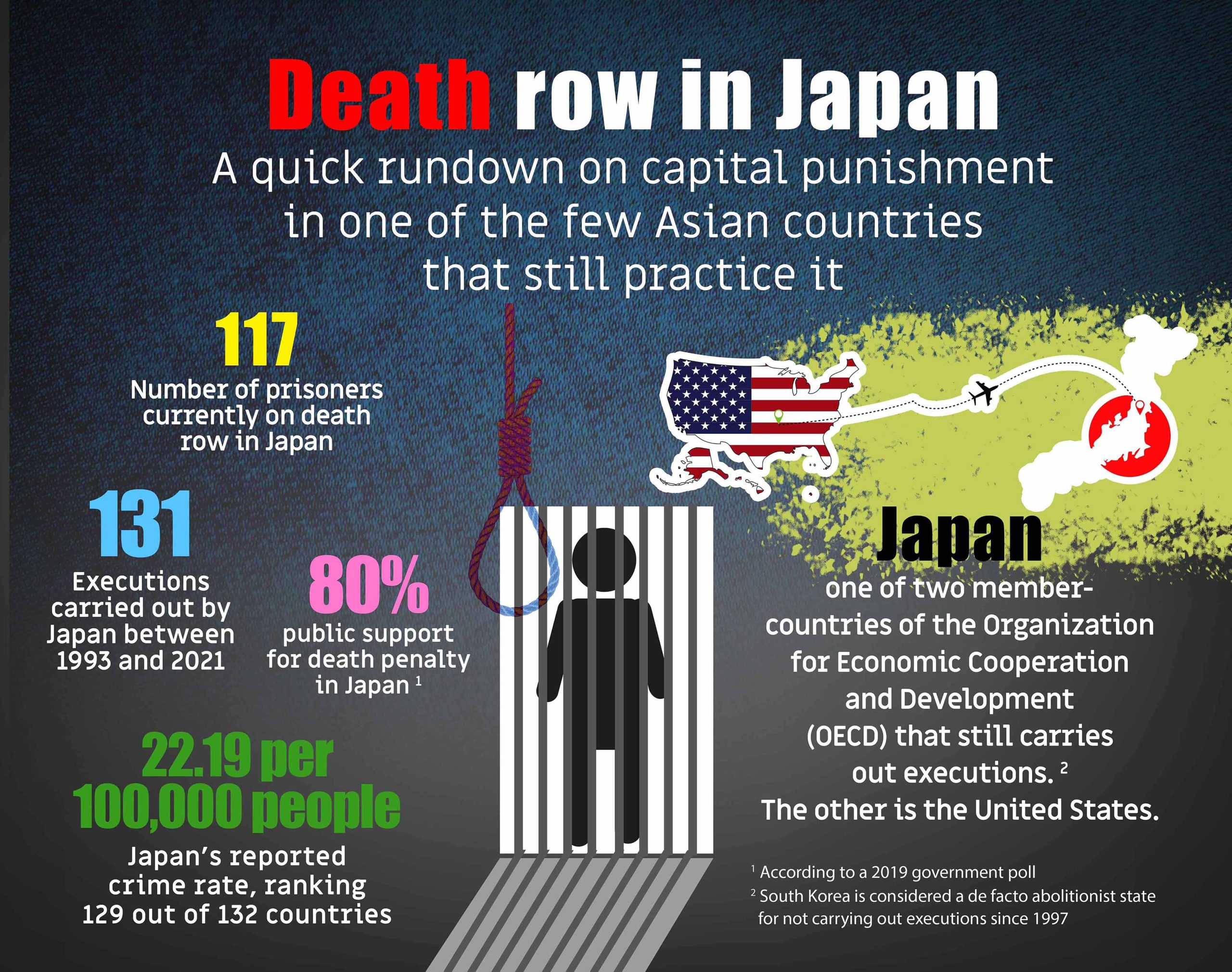

Of the 38 member-nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Japan is among the only three that still impose capital punishment. The United States and South Korea are the other two, but the latter is considered a de facto abolitionist state, having had no executions since 1997.

The death penalty, though, remains popular in many parts of Asia. In Southeast Asia, only the Philippines and Cambodia have abolished capital punishment.

In Japan, rights advocates view the case of Iwao Hakamata as yet another example why the country’s justice system is in need of reform. A former boxer, Iwao’s conviction had been based primarily based on his confession that was made after nearly three weeks under detention, and without the presence of a lawyer. He later retracted his confession and said during his trial that the police had beaten him up and forced him to confess.

“Once arrested, a person in Japan is viewed as guilty,” comments Machiko Ino, who heads the Hakamata Support Club that has more than 300 members. She adds, “The death penalty is dangerous and can murder innocent people.”

Defense lawyer Kouji Mizutani also remarks, “I strongly doubt the state has the authority to decide that a particular person has zero value to keep living.”

Death by hanging

Japanese prosecutors commonly demand the death penalty for those who commit multiple killings. But there have also been cases where capital punishment was meted out for single murders that were considered particularly heinous.

In the past decade, the death penalty has been handed down in at least five cases each year nationwide. According to the Japan Innocence and Death Penalty Information Center website, there are currently 117 prisoners, including eight women, on Death Row in the country. The Center also says that of the present Death Row inmates, six are non-Japanese while five were minors at the time of their alleged crimes.

Japan executed 131 Death Row prisoners between 1993 and 2021. It did not carry out executions in 2020, but then hanged three people in 2021 and one in 2022. Each had had been convicted of multiple murders. One of those hanged in 2021, Onokawa Mitsunori, had a pending retrial petition when he was executed.

Like many other Asian countries, Japan’s mode of execution is by hanging. According to the government, the convict loses consciousness immediately once he or she is dropped. Mizutani, however, describes the practice as feudal and cruel.

He recounts that in one case where he and his team argued against the imposition of the death penalty on a man accused of killing five people and seriously injuring 19 others, he provided research that showed long-drop hanging—a fall of about three to four meters—carried the risk of prolonged suffering, massive bleeding, and decapitation, depending on the weight of the person. Yet, Mizutani says, during hearings and subsequent appeals, the Osaka District Court, the Osaka High Court and the Supreme Court supported the death penalty, arguing that “some pain is inevitable.”

Mizutani belongs to a legal group calling for abolition of hanging as a first step toward penal reforms. But criminologist and Ryukoku University professor Shinichi Ishizuka says that deep-rooted conservatism in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party makes change in that direction an uphill struggle.

“It is not common for Japanese society to challenge authority,” he says. “Hence the lack of information for the people to make an informed decision.”

Critics of the death penalty say as well that the lack of information has staunched a crucial public debate that can promote reform. Indeed, a 2019 opinion poll conducted by the government on capital punishment revealed high public support for it: 80 percent. Japanese media reports on the slandering of criminals and their families, particularly on social media, also cite comments such as “A person who takes the lives of others should not be alive or should take responsibility.”

Hideko Hakamata herself says, “The only way I could protect my brother against an inhuman system was to meet him once a month. I rejected the constant criticism from neighbors and other family members for meeting him. Japanese society doesn’t respect the human dignity of prisoners.”

“A long, hard look”

Ishizuka says, however, that after he demonstrated in class the suffering caused by hanging—the extreme fear of the prisoner, the lack of family at the time of death, and the secretive atmosphere—many of his students were no longer inclined to support the death penalty. They also discussed the necessity for more humane treatment of prisoners, he reports.

There are signs as well that some Japanese are now trying to look more closely at what could have motivated someone who has been accused of a crime – and ending up being among his or her supporters. For instance, Tetsuya Yamagami, who was arrested last year as the prime suspect in the assassination of former prime minister Shinzo Abe, has become the beneficiary of fund drives set up by citizens moved by media stories about his background.

Yamagami’s mother was apparently part of the Unification Church that allegedly dupes its followers of their money. Their family was driven to financial ruin and Yamagami was unable to go to university as a result. He had somehow seen Abe as being among those who enabled the Church to grow in Japan.

Kei Saito, whose parents also belonged to Unification Church, joined one of the groups supporting Yamagami. She says, “I am keenly aware that Yamagami was pushed to the wall given the loss of family and fortune. I am worried he will not get a fair trial. The state is wrong to kill people who commit a crime because they are desperate.”

A December 2022 editorial in the Mainichi Shimbun had also urged Japan to “take a long, hard look” at the death penalty. It noted in part: “The death penalty demands a person to atone for a crime with their life. But of course, even if a person is found to have been falsely convicted, there is no hope for them should the exculpating evidence be discovered after their execution. And there is growing momentum toward abolition globally.”

“Here in Japan,” it said, “four people sentenced to death were ultimately acquitted in retrials in the 1980s.”

Supporter of capital punishment, though, argue that it is a vital crime deterrent and point to Japan’s low national crime rate as proof. On the World Population Review website, Japan is ranked 129 in a list of 135 countries and territories, with a crime rate of 22.19 per 100,000 people.

A 2020 analytical study by legal expert Daisuke Mori of the Kumamoto University Faculty of Law, however, found that “(neither) the death sentence rate nor the execution rate has a statistically significant effect on the homicide and robbery-homicide rates.”

Mori did have a caveat. He wrote that “although I found that death sentences and executions have no statistically significant effects, it does not mean that they do not have a deterrent effect,” allowing that “a fundamental point of logic when testing hypotheses is that failure to reject a null hypothesis does not imply that the null hypothesis is correct.”

Still, among his other findings were that while life sentence rates had a “significant negative effect” on the robbery-homicide rates, unemployment rates had a “significant positive effect.”

Ironically, too, the death penalty itself may actually be tempting people to commit murder. In November 2021, for instance, a man attacked at least 16 people – one critically – in a train because, he said later, he wanted to get the death penalty. That was also the motive claimed by a teenage girl who was arrested just last August for the attempted murder of two people.◉