|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

I

nitially, the family of Satyapal Singh did not want him to join the march because of his age. But the 75-year-old resident of the Indian northern state of Uttar Pradesh said that he “insisted and starved to convince my family.”

“When my son finally told me to go, I took some pairs of clothes in a bag and a water bottle with me,” Singh recounted. “I joined the march in the neighboring state of Telangana.”

That march was the Bharat Jodo Yatra (BJY) or Unite India March led by Rahul Gandhi of the opposition Indian National Congress party. It began on 7 September 2022 in India’s southernmost tip Kanyakumari and ended just this 30 January in Srinagar, the summer capital of India-administered Kashmir. By then the march had gone through 12 states and two Union Territories, and had covered more than 3,500 kms.

BJY has been regarded as a major political campaign by the Congress party in the run-up to this year’s series of state elections and the 2024 national polls. It is also said to have been an attempt to revive the image of Gandhi, a scion of the Nehru-Gandhi clan that used to dominate Indian politics but who has himself been demeaned and portrayed as incompetent and entitled by leaders of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

In fact, in the years that Gandhi was either Congress’s official president or its de facto leader, the party faced repeated defeats in national and state elections. Currently, the once mighty Congress has just 53 of the 543 seats in Parliament; BJP has 303 seats.

Yet while it still remains to be seen whether or not Congress’s grand march for unity will help bring good political tidings to the party and Gandhi, many are hopeful that the message it sought to spread will thrive and eventually overpower what some have described as the “hate politics” of BJP.

Congress leaders repeatedly said that the yatra was against the rising politics of hate and bigotry in India, rampant unemployment, the economics of livelihood destruction, and growing inequality. “At present, India is divided on religion,” said Gandhi, addressing media in the Jammu division of Kashmir. “If we are together, we will be able to overcome the hatred of the present day.”

“For me, this is not a political march, but a mass movement that carries forward the secular legacy of India,” said Urmila Matondkar, a Bollywood actress who joined the march in Jammu. “India was a place of harmony and brotherhood, and it will stay like that.”

Farmer Ashok Singh, for his part, said that he had always felt proud of India’s secular and pluralistic fabrics. But he said that over the years, India witnessed growing communal violence, with one section of the community being pushed to the margins.

“We will never allow anyone to break our country,” Singh, who joined BJY from Haryana state, told ADC. “We will fight day and night to secure the secular fabric of our country.”

Unite vs. divide

That fight, however, is bound to be long and hard. Indeed, the ruling party not only constantly attacked Gandhi and Congress during the march, it also managed how the BJY would be covered by the mainstream media. Journalist Sanjay Kapoor noted in an article published in the Deccan Herald some three weeks before the march reached Kashmir: “Whenever the Yatra gets any coverage, it is about the trivia of why Rahul Gandhi is wearing a t-shirt in bitterly cold conditions rather than the support it is getting. Expectedly, many reporters are seeking bytes from everyone on why Rahul is not feeling the cold rather than his message of communal amity.”

BJP leaders meanwhile called Gandhi’s yatra a mere eyewash and meaningless exercise. “All along the yatra, Mr. Rahul Gandhi has walked with people who have been working to divide the nation,” BJP President Jagat Prakash Nadda said in a statement. While the BJP has an agenda of vikas (development), he added, Congress’s agenda is vinash (destruction).

And yet it is no secret that BJP’s rise to political prominence is due to its promotion of Hindutva ideology and its strategy of fighting elections along communal lines. Indeed, ever since BJP came to power in India in 2014, several of its leaders have been accused of orchestrating hate speeches, with the country’s Muslim minority of about 200 million as the frequent targets. As recently as last 25 December, BJP legislator Pragya Singh Thakur, addressing a gathering in Karnataka, urged Hindus to “keep weapons at home, keep them sharp. If veggies can be cut well, so can the enemy’s head.”

Anecdotal and media reports both suggest that communal violence has been on the rise under the BJP. Union Minister of State for Home Nityanand Rai himself has said that over 2,900 cases of communal or religious rioting were registered in the country between 2017 and 2021. Citing National Crime Records Bureau data, Rai said that a total of 378 cases of communal or religious rioting were registered in 2021, 857 in 2020, 438 in 2019, 512 in 2018, and 723 in 2017.

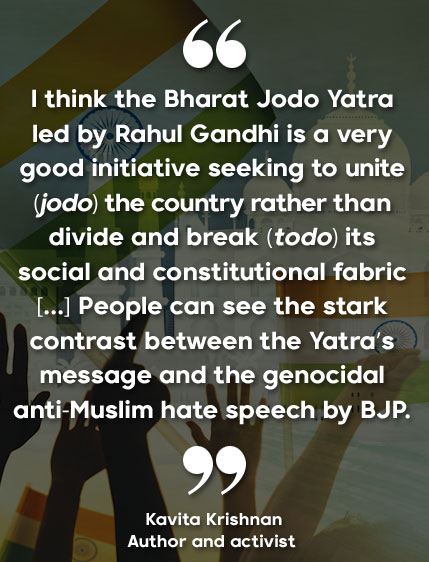

“I think the Bharat Jodo Yatra led by Rahul Gandhi is a very good initiative seeking to unite (jodo) the country rather than divide and break (todo) its social and constitutional fabric,” said author and activist Kavita Krishnan, who is also a former member of the Communist Party of India Liberation. “People can see the stark contrast between the Yatra’s message and the genocidal anti-Muslim hate speech by BJP MP Sadhvi Pragya.”

Graduate student Adil Lateef Sheikh said that he saw a ray of hope in BJY amid the ongoing oppression of Muslims in India, particularly in Kashmir. “BJP wants to completely disenfranchise Muslims of Kashmir,” he said. “This yatra has reignited hope among Muslims in India that there are leaders who can speak for them.”

Songs, slogans, and staying on

Although there is no official figure on just how many people participated in the march, observers say there were at least tens of thousands at every stop. The marchers were also of different religious, political, and professional backgrounds, and of wide variety in ages. Most joined the march for just segments of it, but some people stayed on, marching until it concluded in Srinagar.

“It was the 50th day of BJY when I joined,” said the septuagenarian Satyapal Singh. He said that he had planned to walk just a few miles with BJY and then return home, but the passion and love among the marchers compelled him to keep on walking with them until the final stop.

The march covered more than 20 kms or so each day, with a break between two shifts. As it moved forward, participants would sing or shout slogans, including “Mile Kadam, Jude Vatan (Walk Together, Unite the Country),” “Mehengai Se Nata Todo, Mil Kar Bharat Jodo (Break Ties with Inflation, Unite India),” “Berozagari Ka Jaa lTodo, Bharat Jodo (Break the Web of Unemployment, Unite India),” “Nafrat Chhodo, Bharat Jodo (Quit Hate, Unite the Country).” and Samvidhan Bachao (Save the Constitution).”

For sure the march has revived the once-flagging spirits of Congress members and leaders. On 26 January, Republic Day, the Uttar Pradesh Congress launched its campaign ‘Hath Se Hath Jodo,’ an extension of the BJY, with the aim of spreading the message every household in the state for the next two months.

“The Bharat JodoYatra has received immense support and lakhs (tens of thousands) of people have connected to us through this yatra,” Congress President Mallikarjun Kharge said while addressing the public at the march’s end in Srinagar. “This country belongs to all of us, but our Constitution and democracy are at risk and it is quintessential to save it (sic).”

“If you are united irrespective of religion, caste, color or creed, no one will break you,” said businessman Raman Kumar of Telangana state, who was pumping his arm up and down as he shouted “Bharat Jodo (Unite India)” before ADC caught up with him. “I joined BJY because I saw love and affection in the eyes of Rahul Gandhi for this India. He is the one who knows how countries grow and prosper.”

“The BJY did two things for sure,” said Anand Dev Yadav, a resident of Varanasi, a city in Uttar Pradesh. “It has wiped out Rahul Gandhi’s image of the incompetent leader and it has sent a clear message to BJP that there is someone who can defeat them and fight for the secular fabric of India.”

Yet he admitted, “Congress has still a lot to do to defeat BJP in the 2024 elections.”

For now, though, those who had been part of the yatra are basking in its feel-good afterglow. And while many of them know more work lies ahead if its message is to prosper, they are also expressing satisfaction in being able to make a stand – or march, in this case – out in public. Said Satyapal Singh, who nearly missed the yatra because his family thought he was too old for it: “If tomorrow anybody would ask me what I had done when my country was burning with hate, I will say I took part in BJY.”◉