|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

When democracy advocates across Asia gathered in Bali last November for the 2022 Asia Democracy Assembly, they did so in an atmosphere of uncertainty. In one week, the most significant world leaders would gather in Nusa Dua, just 14 kms away, for the G-20 meeting. Some participants entered the conference room with a sense of urgency that was not easy to convey. Fortunately, it didn’t take long until their grievances were brought to life.

“We are living in a world that is absolutely troublesome,” said Jose Ramos-Horta in his pre-recorded opening speech from Dili. Speaking with his statesman charisma, the Timor-Leste President delivered a sobering exposition of the state of the world today: “It is not acceptable that tens of billions of dollars are easily found for Ukraine. Profits are made from wars in Afghanistan, Yemen, and Syria. And yet we cannot mobilize hundreds of billions of dollars to end extreme poverty, malnutrition, to bring clean water to the poorest villages of the world, and to support developing countries in renewable and clean energy.”

Timor-Leste, Ramos-Horta said, is an “oasis of tranquility in an otherwise troubled region.” Like other countries, the tiny Southeast Asian nation had suffered economic fallout from COVID-19 lockdowns. It also experiences flash floods—exacerbated, undeniably, by the global climate crisis—that destroys much of its agriculture and displaces thousands of people each time.

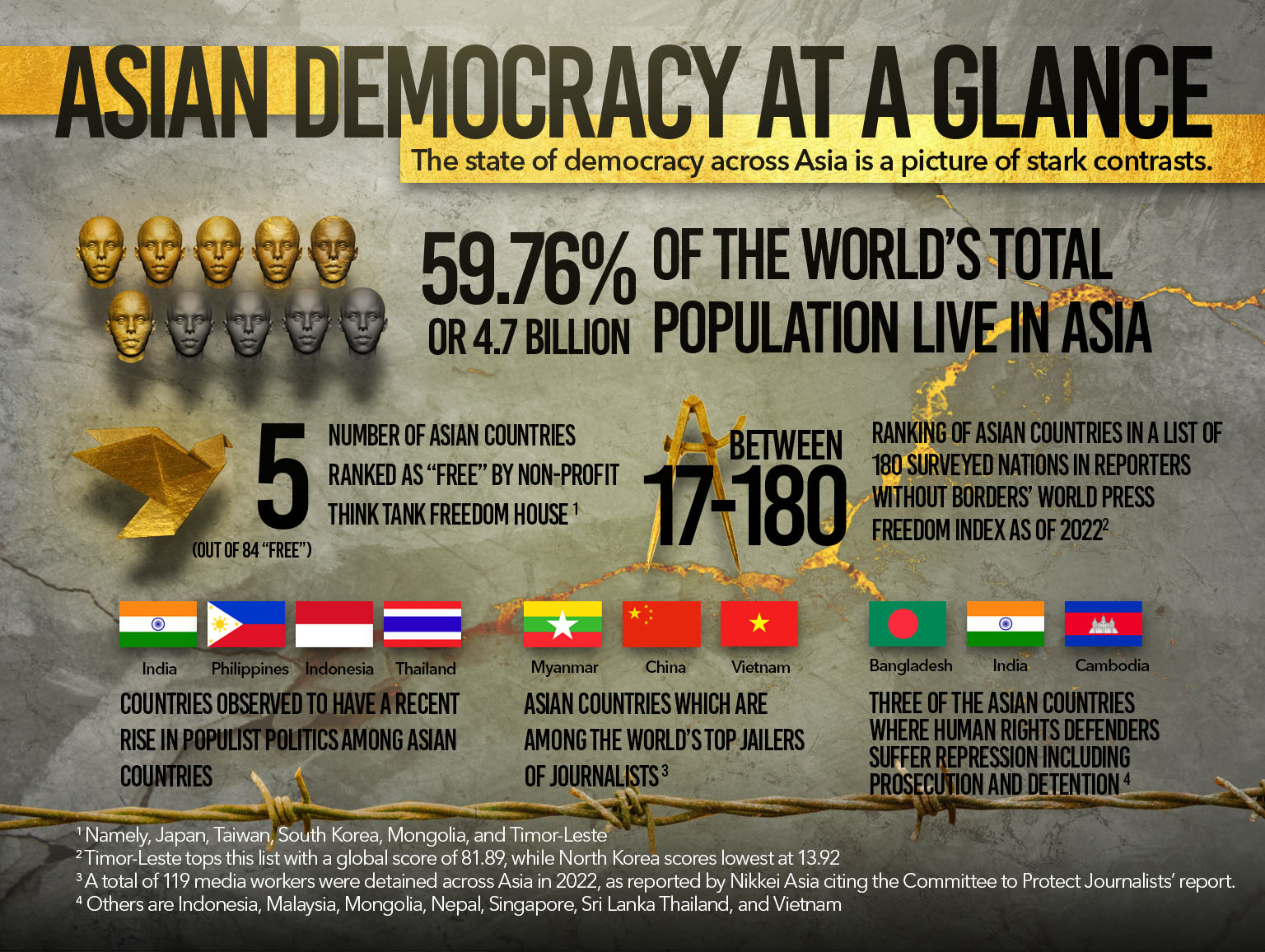

Yet despite all these, Timor-Leste has largely remained committed to democracy. It scores highest amongst all Asian countries in the World Press Freedom Index, ranking 17th globally; is one of only five nations in Asia to be considered “Free” by Freedom House; has a continuously high voter turnout; and managed to double the number of women being elected to governance.

The same cannot be said of most other Asian nations, where democratic systems are either stagnating, backsliding, or being obliterated. There is no lack of fingers being pointed to forces perceived as the culprit behind this crisis. While the global expansionist agendas of rapidly growing economic powerhouses in the East have been accused of dismantling social protections in multiple countries, the West is no longer free from culpability either, especially as its propagation of “universal security narratives” has inadvertently justified domestic surveillance and abusive counter-terrorism measures.

To Yukio Takasu, Japan’s former representative to the United Nations, the idea of building democratic solidarity under the shared umbrella of “universal values” has become more difficult than ever.

“You shouldn’t blame everything on these countries, of course,” Takasu said. “But China and Russia are claiming that they are better democracies than ours (sic). For them, theirs is the genuine democracy, while other types of democracies are just ‘formats.’ Of course, they also say that they are the best defenders of human rights, because they ‘know’ what is best for their people.”

Not all is bleak, though. In the midst of the global democratic deficit, democratic movements in Asia have continued to demonstrate their grit —and even more urgently in situations where hope for a reversal of intensifying state repression seems scarce.

At the Bali gathering, speakers conveyed stories and ideas that emphasized the possibility of change without betraying the gravity of the situation: from the triumph of the Indian farmers’ protests to the breakthrough in promoting women’s rights in Indonesia by fostering alliances with female ulemas, democratic efforts have kept finding novel ways of promoting norms, scaling up movements, and influencing policies across the region.

Against international paralysis

Consider what has been happening in Myanmar. Two months after the February 2021 military coup there, leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) convened in Jakarta to devise a peace plan. The resulting Five-Point Consensus called for an immediate end to violence in Myanmar, a dialogue between conflicting parties, and the appointment of a special envoy from ASEAN to facilitate peacebuilding there.

Two years later, ASEAN countries are still latched on to the Consensus. But actual progress has been mostly non-existent. Junta leader Min Aung Hlaing was barred from attending the latest ASEAN summit in November 2022, but the meeting reaffirmed Myanmar’s position as “an integral part of ASEAN,” followed by the extremely lukewarm call for junta forces to comply with its commitments. In other words, not much has taken place aside from ineffectual moral condemnation—and the Myanmar democratic resistance is very much aware of this.

“You see banners that say: we are not going to rely on the international community. For our people’s liberation, we’re going to fight ourselves,” said democracy activist Khin Ohmar, founder and chair of Progressive Voice, in Bali. “This is the general sentiment of the Myanmar people at this moment, because after 22 months, we’re not getting any international help.”

After a year of political revolt bolstered with armed resistance, Myanmar’s civilian National Unity Government (NUG) was reporting that the alliance of its defense forces and their Ethnic Revolutionary Organisations (ERO) counterparts had finally assumed control over half the country. NUG had set up public administration and judicial systems in 24 different townships, along with education, health, and social services, acting President Duwa Lashi La said.

But that might not last very long as the junta ramps up airstrikes, targeting even concerts such as one in Kachin state last October where the attack killed some 80 people.

A U.N. Special Rapporteur reported that China and Russia had been supplying the Myanmar military fighter jets, armored vehicles, and ballistic missile systems since 2018. Serbia, too, was singled out as authorizing the transfers of rockets and artillery.

“Yet the UN and ASEAN treat the junta as if they are where the solution lies,” said Ohmar. “They’re getting it so wrong! Because the solution for Myanmar to solve the crisis, to move forward, is to establish a federal democracy. And this lies in the hands of the Myanmar people, especially the young generation.”

So where did this international paralysis come from? According to International Commission of Jurists senior international legal adviser Kingsley Abbott, new, debilitating trends have emerged in the authoritarian playbook across Asia. Illiberal regimes would draft draconian laws that cast a wide net against activists, and then take them to kangaroo courts, claiming they are merely implementing the rule of law.

“There are very concrete examples [of people I know] sitting down with governments, and they simply receive a lecture that it would be improper to interfere with an independent legal process,” Abbott said. “That these countries have their own independent justice systems and their own laws (seems to mean) … we all should just wait for the justice system to conclude. It is thus increasingly difficult for civil society and for the international community to react.”

On a more substantial level, this implies that democratic institutions — including the judiciary and parliaments — are being abused for non-democratic means. While oligarchs across Asia increasingly rely on “state capture” for impunity, an absence of check-and-balance can lead to truly catastrophic consequences.

Learning from Sri Lanka

Such is the case of Sri Lanka. When Gotabaya Rajapaksa was appointed President in November 2019, no one predicted that his reign, earned with a landslide poll victory that was based on a Sinhalese ethnonationalist campaign, would unravel in such spectacular fashion. Yet despite his (and his clan’s) absolute rule, Rajapaksa turned out to be a painfully incompetent oligarch.

Amid massive protests, Rajapaksa in mid-2022 departed in a frigate from Colombo harbor, fled to Maldives and then to Singapore, where he finally conceded defeat; he resigned as President via email on 14 July 2022. In Colombo, ecstatic protesters stormed the abandoned Presidential residence and occupied it with revolutionary cheer, and even swam in its pool.

But the worst of Sri Lanka’s hardships was yet to come. Centre for Policy Alternatives founder Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu said, though, that Sri Lanka’s current economic crisis is largely the result of its government buying out its citizens’ votes.

“Ever since our independence, each government has offered 10,000 jobs in public service and 10,000 more rupees for those who work in that sector,” he said. “As a consequence, we have 1.5 million public-service workers for a population of 22 million. That is simply unsustainable.”

Saravanamuttu also quoted former Singapore Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, who had remarked that “Sri Lankan elections are an auction of non-existing resources.”

Sri Lanka’s electoral system indeed has been problematic, said elections observer Damaso G. Magbual. He added, “There is unmitigated use of money to influence voters. In the last parliamentary elections in Sri Lanka, in the first two weeks of the campaign alone, a candidate for parliament spent equivalent to 66 months of salary for a 60-month job.”

Some commentators characterized the protests as a revolt rather than revolution — meaning these sought only regime change, and not the transformation of fundamental social or property relations.

“Basically, Sri Lanka — and I guess this is probably also the case with a number of our Asian neighbors — have to rewrite our social contract,” Saravanamuttu said. “We need to come up with a platform where we get rid of all powerful executive Presidency and return to parliamentary democracy. We need to change our electoral system so we can allow new people to participate, especially women.”

Renewing the case for democracy

The question is, what kind of social contract is needed to ensure that democracy and the rule of law are being upheld, and how do we forge it? That isn’t easy to answer, though — especially amid the socio-political and economic struggles across Asia.

In Malaysia and Indonesia, entrenched oligarchs are continuously losing ground over their political legitimacy, but opposition forces — if they even exist —have proven unable to build upon the widespread disenchantment and offer a convincing vision. Singapore and Japan keep striding along the path of economic development and seem convinced that other concerns regarding civil rights are largely irrelevant. Meanwhile, the Philippines and India are still absorbing the full impact of experiments with right-wing populism to their social fabric.

While the democratic crisis unfolds in different permutations across the region, two things are at stake. First, pro-democracy activists need to come up with a reliable diagnosis on why our democracies are backsliding. For example, one prevalent trajectory in which states drift toward autocracy occurs when they “temporarily suspend” democratic procedures in the name of safeguarding economic growth and social stability, as what happened in the curbing of public protests and civil freedoms during the coronavirus pandemic.

Such false dilemmas reflect a historically problematic framework on the role of democracy. At the end of the Cold War, democratization in Asia typically asserted that political freedom cannot be separated from economic growth. Within this “modernization” framework, international bodies saw that opening closeted, autocratic states to the free market would give rise to a burgeoning middle-class, which, in turn, would compose a robust civil society that acts as a natural foil against authoritarianism.

This framework has not shown that economic growth necessarily leads to a more democratic polity either. In particular, China has presented itself as an alternative to this trajectory with its middle-class boom and record-breaking economic development, but whose authoritarianism at home shows little signs of dissipating soon.

“There is actually mixed evidence in academic literature whether well-performing economies can bring greater political participation, or that poor economies actually create much more demands for greater democratization,” said Dr. Khoo Ying-Hoi, head of International and Strategic Studies Department of the University of Malaya. ”There are some puzzling case studies that we can look at. Look at Singapore. Look at Brunei. They don’t really quite fit the standard formula that we are looking for. How do we unpack this?”

Second, social movements and civil-society organizations need to present a reinvigorated vision of democracy that is both appealing and feasible. As Sri Lanka’s experience shows, any proposal of a “new social contract” needs to posit democracy as the solution to economic and social crises. Democracy is not only an ideal that works; it also needs to be workable upon.

“We can only have good development outcomes if we have good governance, and we can only have good governance if we are able to influence those who are in politics,” said Mardi Mapa-Suplido of INCITEGov, a Philippine research and advocacy center. “When we say we want good governance as part of democracy, what we mean is that all sectors, particularly the vulnerable and marginalized, are part of that whole decision-making process so that they can deliver equitable development outcomes needed in our country.”

“We can only have good development outcomes if we have good governance, and we can only have good governance if we are able to influence those who are in politics,” said Mardi Mapa-Suplido of INCITEGov, a Philippine research and advocacy center. “When we say we want good governance as part of democracy, what we mean is that all sectors, particularly the vulnerable and marginalized, are part of that whole decision-making process so that they can deliver equitable development outcomes needed in our country.”

There are real ways in which civil society can meaningfully engage with their leaders. For example, said Mapa-Suplido, in bottom-up budgeting, NGOs and community stakeholders are involved in determining what their community needs, steering away local or national governments from vanity projects or one-sidedly defining the best course of development. A more proactive method to gain a seat at the table, she argued, is to seek reform-oriented local officials and facilitate their engagement, along with building a country-level democracy network to consolidate a viable political opposition.

These efforts will not only bolster the ranks of our pro-democracy movements, but also enable us to channel our ideals into actual projects, securing small wins along the way. One analogy for this process is the “reverse jenga”: often, our movements start off by being vulnerable and unconnected from one another, and the main task is to fill in the missing gaps in our movement infrastructure.

To Migrant Forum Asia regional coordinator William Gois, these steps are quintessential for the success of the democratic movement in Asia. He said, “To build a new kind of resistance where mobilization and organizing is at the heart of it, to have a new political style at work, and to look at how we work with the young people today who will take this struggle further… Some of us took 10 years to do what they have been able to do in a year. So there is a lot of learning that can happen. A lot of exchanges can happen.”◉