|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

I

n a residential Delhi suburb, women sort through huge piles of used LED bulbs, batteries, and more, tossing unusable parts into a smouldering fire. Their little children play nearby, occasionally rubbing their eyes and coughing from the smoke.

“We’re all used to it,” says Rukmini (not her real name) who has been working here for the last six months, for a monthly income of about US$73. “I can’t remember a morning when I woke up without a blocked nose and itchy eyes. But this is the only work available here. We do it to survive.”

A supervisor rushes out when he sees us. “No photography!” he shouts, shooing the children away.

Burning of waste in such illegal waste-segregation units, endless construction on unpaved roads, and proximity to a busy highway have made Loni in Ghaziabad, Delhi’s neighbor, one of the top polluted hotspots in India’s Delhi-National Capital Region (NCR).

Twelve kms away, Anand Vihar, a locality in East Delhi, routinely records some of the highest levels of air pollution in Delhi-NCR. There, local auto rickshaw driver Arbaaz Khan always has a piece of cloth wrapped around his nose as he drives all day in his open vehicle. By day’s end, the cloth is filthy and calling for a wash.

“While Delhi has banned diesel vehicles older than 10 years, I see old buses continuing to ply in (adjoining) Ghaziabad, spewing smoke everywhere,” says Khan. “It is hard to breathe, but I guess those bus companies also just need to make a living.”

In Medanta Hospital in Delhi NCR, Arvind Kumar, the capital’s leading chest surgeon and founding trustee of the non-profit Lung Care Foundation, emerges from the operation theatre, where he says that he sees “blackened lungs, even in non-smokers, every single day.”

Kumar says that around 2010, he began noticing an increase in the number of non-smokers developing lung cancer. “I find that these days, whenever air pollution spikes, a week later, hospitals report a 50% increase in heart attacks and strokes,” he says. “And given how polluted the country’s air has become now, I foresee a veritable epidemic of lung cancer in the coming five years.”

“This [air pollution] is a health emergency at the national level,” Kumar continues. “An emergency much greater than the COVID-19 pandemic.”

A dubious distinction

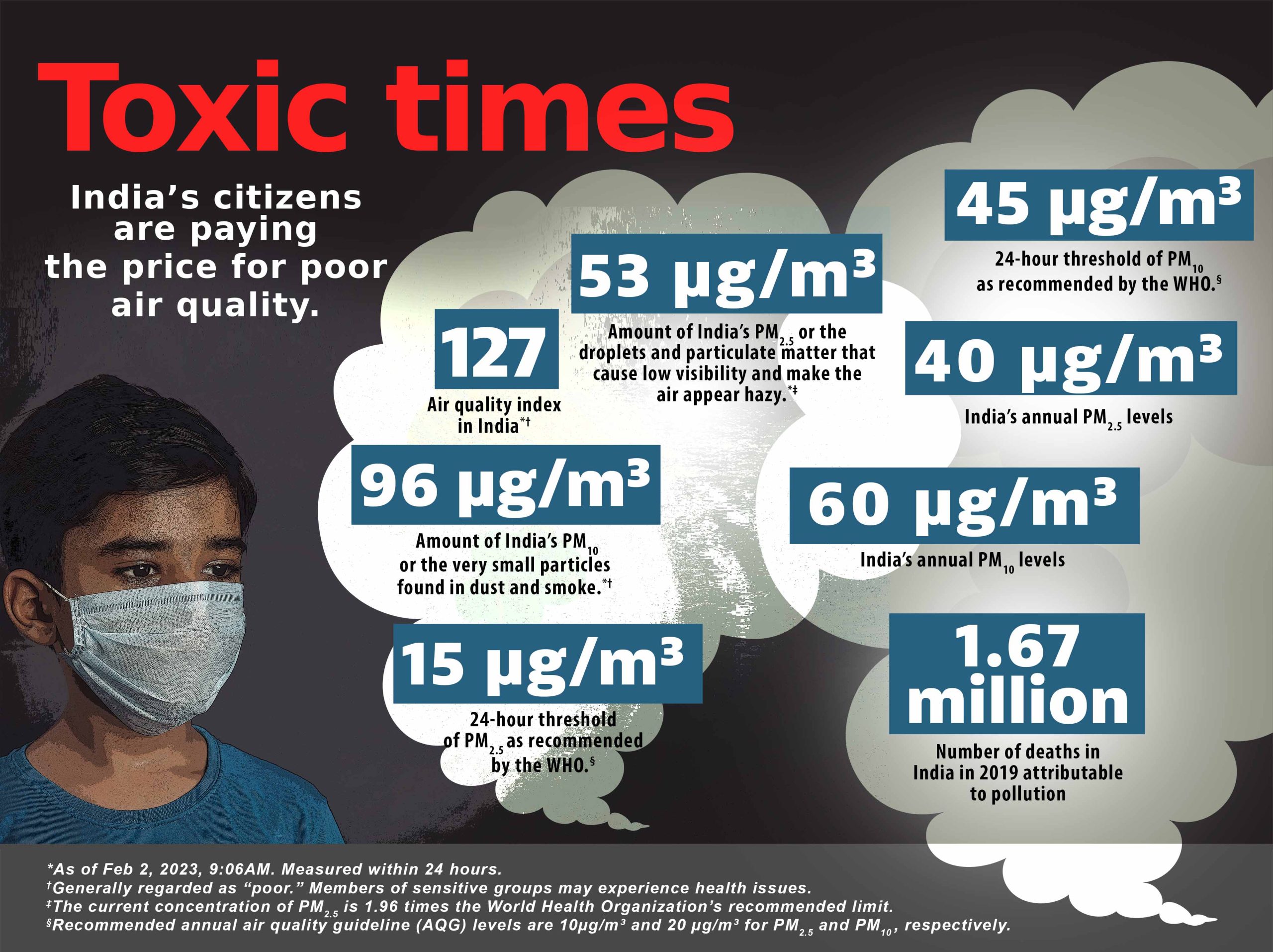

Three years after the ambitious central government National Clean Air Programme was launched in 2019, India continues to rank among the top five most polluted countries in the world. That distinction has had deadly consequences. According to a study published in the journal Lancet Planetary Health, air pollution in India not only accounted for $36.8 billion in economic losses in 2019, it also resulted in 1.67 million deaths that year — the largest pollution-related death toll in any country in the world.

The fatalities attributed to air pollution in India accounted for 17.8% of all deaths in the country in 2019. Air pollution, the Lancet study suggests, could “impede India’s overall economic development and social wellbeing” unless it is “addressed as a priority.”

Kumar explains that prolonged exposure to air pollution affects not just the lungs, but the entire human body, from brain to toe. “Each of us takes 25,000 breaths every day,” he says. “With each breath in India, we are inhaling a poisonous mix of pollutants.”

Physical symptoms, like Rukmini’s inflamed, itchy eyes and blocked nose, are immediately visible. The reason why she says she brings her six-year-old to her workplace — because “he’s too naughty to be left unsupervised” — may also be linked to exposure to airborne toxins. Kumar suggests that air pollution, in addition to causing asthma and pneumonia, especially in young children, could cause neural inflammation. This could make children hyper-excitable and experience a decrease in their attention spans. In the long term, Kumar says, air pollution can cause various childhood cancers, premature hypertension in children, and even reduce their IQ by 10%.

Air pollutants affect all major organs in adults, too. “Yet,” says Kumar, “I find that common people, even many doctors I’ve spoken to, are unaware of the profound health impacts of air pollution.”

In fact, a nationwide survey conducted before the 2019 election found that Indians ranked air pollution only as their 17th most pressing concern. Jobs, health care, and infrastructure were among the top issues that they reported as the most important electoral concerns, with a mere 12% saying that air pollution was a priority. As Arbaaz Khan, who is forced to make his living driving an open auto rickshaw in a pollution hotspot, attests, there is a sense of resignation, if not impotence. “I know the smoke and exhaust fumes are probably bad for me,” Khan says, “but I have to breathe and have to eat.”

With the objective of improving awareness about the dangers of air pollution and promoting viable solutions, a growing collective of Indian doctors has been holding workshops across the country. In 2022, Doctors for Clean Air has made presentations even to fellow doctors in 15 cities across the country, including Jalandhar in Punjab, where they were able to convince some farmers to stop burning crop stubble (long been touted as one of the key activities that lead to air pollution in North India).

In Delhi, the more affluent have started using air purifiers (most costing upwards of US$150 each). Driven by fears of further air pollution, India’s air purifier market is expected to rise at a compound annual growth rate of more than 5% between 2020 and 2025. But doctors say that completely limiting exposure to polluted air is near impossible. Says Kumar: “When people ask me if air purifiers offer a solution, my answer is an emphatic, ‘No!’ You can carry your own water bottle to avoid drinking unclean water outside, but you can’t carry your air purifier around as air is all around us.”

Prescriptions for the future

Indeed, as air pollution is all-pervasive and knows no geo-political boundaries, isolated regional and state efforts to mitigate air pollution in India have been largely unsuccessful.

Clean-air advocates now suggest a mix of small-scale and larger-scale solutions, ranging from replacing manual road sweeping with machine cleaning to switching entirely to low-emission fuels and renewable energy. None of them will be easy to implement in the short term, however.

Mechanized sweeping is now being piloted in Delhi. Mayank Jhinjot of Safai Karamchari Andolan, a movement by sanitation workers that aims to eradicate manual scavenging — performed in India by Dalits, a low-caste community — says that manual sweeping has caused most of his colleagues to develop respiratory issues. But he cautions that replacing manual labor with mechanized cleaning could deprive the Dalits, who are often discriminated against and find it hard to get other jobs, of their livelihood. “Ideally, the government should train manual sweepers and cleaners to operate mechanized road and sewer-cleaning machines,” says Jhinjot says.

Improving public transport infrastructure and switching private vehicles to cleaner fuels would also substantially mitigate vehicular emissions. “For all those who say that this will be very expensive to implement, I can only say that our health is worth it,” an impassioned Kumar says.

In 2021, the Delhi government constructed a smog tower in its commercial center, Connaught Place, that could potentially halve the number of toxic pollutants within the radius of 1 square kilometer. Critics, though, speculate that such towers are likely to be as effective in cleaning pollutants from the atmosphere as air conditioners installed outdoors on a hot day would be in bringing the temperature down.

Instead of such isolated efforts to clean air, clean-air advocates suggest a science-based approach that takes topography into account. Delhi lies on the Indo-Gangetic plain, a 700,000-sq km landscape that encompasses most of northern and eastern India, around half of Pakistan, virtually all of Bangladesh, and the southern plains of Nepal. Scientists call this an “airshed,” a region that shares similar meteorological conditions and essentially functions as a single unit for pollution particles to float in. Whenever winter approaches and wind speeds reduce, PM2.5 pollutants become concentrated in this airshed as the Himalayas to the north prevent these particles from moving out of the plains. This airshed needs to be treated as a whole to mitigate its air pollution.

To this end, in December 2022, the World Bank and Nepal-based International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, an intergovernmental organization that works to conserve the environment and culture of the Hindu Kush Himalayas, brought together the four countries sharing the Indo-Gangetic Plain airshed to discuss their air-quality challenges and collectively tackle the issue.

How and when such a transboundary effort will pan out remains to be seen. Meanwhile, Delhi resident Rukmini stokes the bonfire into which she and other workers are tossing plastic wire casings, keeping the copper wire aside for recycling. The smoke rises and blends into the smog that shrouds Ghaziabad. As India makes its slow crawl toward net-zero emissions by 2070, Rukmini — and her six-year-old son’s — right to breathe clean air, is being obscured by the toxic haze. ◉