|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

T

he hardline Islamist group Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) is staging a vicious comeback in its home country, rattling residents in northwestern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province where it once reigned, and enraging officials in Islamabad.

Pakistan’s security officials are now pledging “zero tolerance for terrorism.” But Pashtun nationalist leaders and some political parties in northwestern Pakistan say Islamabad has only itself to blame for the group’s resurgence, pointing to what they say has been Islamabad’s soft-pedal policy toward TTP that included agreeing to support peace talks.

“TTP attacks that are mostly concentrated in Pakhtunkhwa province and are part of a deepening insurgency are bound to acquire the shape of a new dangerous armed conflict leading to death and destruction on a large scale,” warned Afrasiab Khattak, a senior leader of the National Democratic Movement (NDM) and Pashtun nationalist, in an interview with Asia Democracy Chronicles (ADC). “Pashtuns are mainly in the eye of the storm in this conflict, but it will also further aggravate socio-economic crises in Pakistan. Pashtun political activists have been speaking about it, but the security tsars have remained in denial.”

The Pashtun is among Pakistan’s ethnic minority groups. In Pakistan, where they make up about 15 percent of the country’s more than 231 million people, Pashtun live mostly in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which borders Afghanistan.

Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, however, recently said that the “policy of appeasement” toward the TTP has been ended by the current government. In an interview with Al Jazeera, Zardari laid the blame for TTP’s continued belligerence on the previous administration that was led by Imran Khan — who interestingly enough considers Khyber Pakhtunkhwa his bailiwick. According to Zardari, Khan had followed “a wrong approach” by going soft on TTP.

Since unilaterally ending a ceasefire with the Pakistani government late last year, TTP has launched several violent attacks across the South Asian country. In fact, soon after it announced it was done with the ceasefire, TTP carried out attacks that included a suicide bombing in the capital Islamabad on Dec. 23, 2022, in which a police officer was killed and several other individuals were injured. The bombing took place only days after TTP members held security personnel hostage in Bannu, a city in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, for 40 hours until the militants were killed by state commandos in a rescue operation.

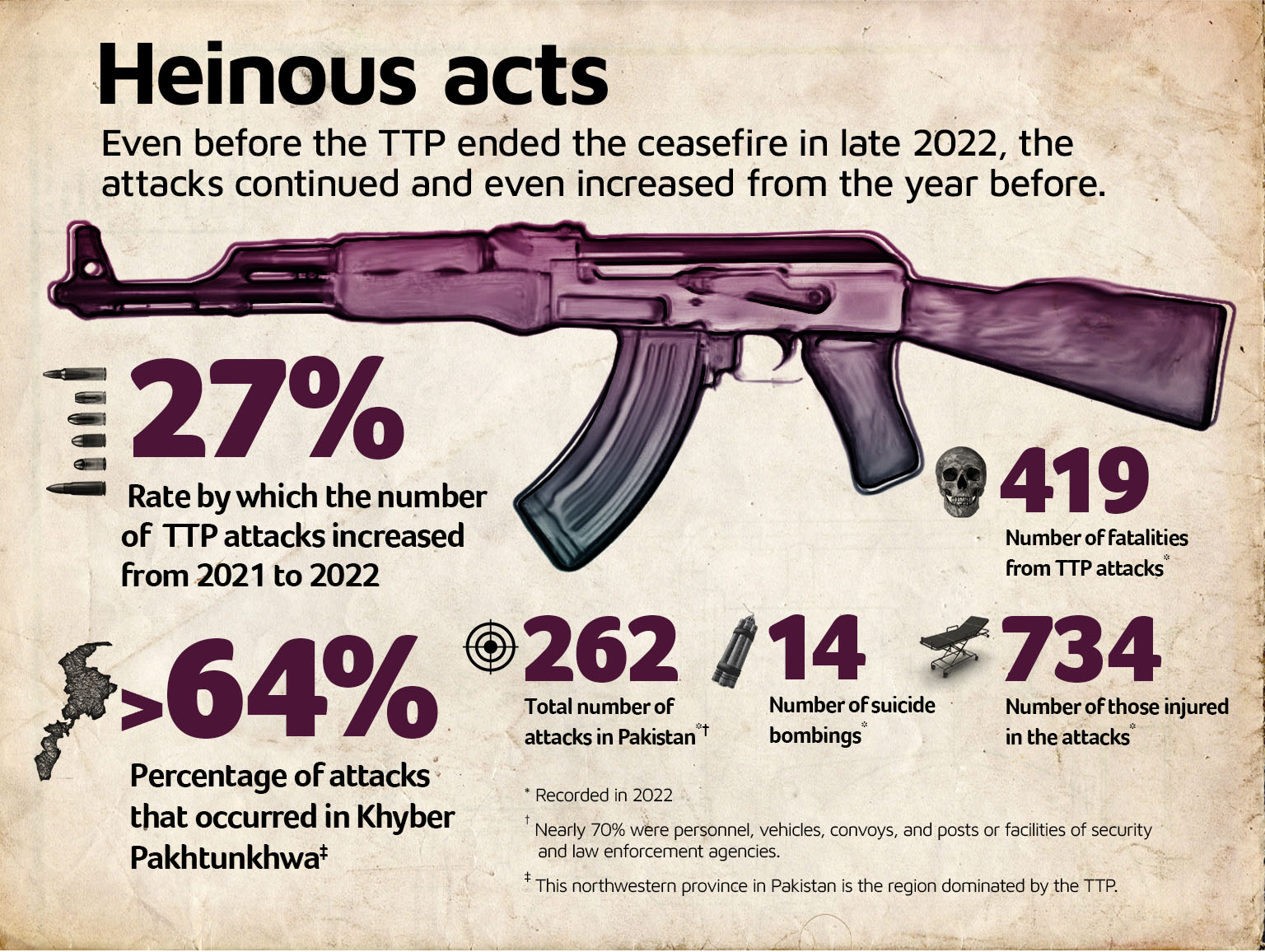

Before — and some say even during — the ceasefire, TTP had also been busy. According to the Pakistan Institute of Peace Studies (PIPS), an Islamabad-based policy research and advocacy think tank, a total of 262 militant attacks were carried out across Pakistan in 2022, including 14 suicide bombings that killed 419 people and wounded 734. Most of these attacks were claimed by TTP. PIPS also says that the number of terrorist attacks in Pakistan in 2022 increased by 27 percent from the previous year.

Analysts think TTP’s re-emergence is cause for concern in terms of the rising number of attacks amid the growing political activity, as 2023 is an election year.

“The TTP have renounced talks, increased their attacks, broadened the geographic scope of their operations, and redeveloped a strong in-country presence after nearly a decade of being based largely in Afghanistan,” Michael Kugelman, a South Asia expert at the Washington-based Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, told ADC. “Their re-emergence poses a grave threat to Pakistan — all the more so given that it took so long for the state to come around to the realization that the threat is so serious.”

“The TTP have renounced talks, increased their attacks, broadened the geographic scope of their operations, and redeveloped a strong in-country presence after nearly a decade of being based largely in Afghanistan,” Michael Kugelman, a South Asia expert at the Washington-based Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, told ADC. “Their re-emergence poses a grave threat to Pakistan — all the more so given that it took so long for the state to come around to the realization that the threat is so serious.”

“Since talks are out, Pakistan has the option of doing nothing or launching a new counterterrorism offensive,” Kugelman also said. “Given how serious the threat has become, doing nothing isn’t really an option — and especially with public pressure increasing for Islamabad to act.”

Fear on the rise

Indeed, with the militant attacks on the rise, Pakistanis are bracing for a major disruption of the relative peace they used to enjoy. In Swat Valley in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, residents are already fearful and panicking.

“In the last few months of 2022, we saw a rise in the incidences of attacks on innocent civilians and the sudden re-emergence of TTP in Swat,” Erfaan Hussein Babak, a local resident, told ADC. “The incidents sent a wave of fear among residents, who had witnessed the worst form of terrorism in the past.”

The deadliest attack yet by TTP was the 2014 school massacre in Peshawar, in which 149 people were killed, including 132 schoolchildren. In 2012, members of the militant group shot Malala Yousafzai, now a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, for advocating girls’ education in her native Swat Valley.

An umbrella organization of several hardliner Sunni insurgent and sectarian groups, TTP’s main aim is to throw out the democratic government in Pakistan and implement a strict brand of Islamic Shariah laws. It has been fighting and attacking the Pakistani state since 2007.

Pakistan banned TTP in 2008. The group has also been declared a terrorist organization by the United Nations and the United States. Pakistan’s security forces have launched several military offensives against TTP in the tribal areas bordering Afghanistan since 2009. TTP was eventually pushed into the neighboring country as a result of military operations, but the fighting not only disrupted the lives of millions of Pakistani civilians, especially in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, thousands also ended up dead.

TTP is not directly linked with the Taliban in Afghanistan, but pledges allegiance to it. Since the return to power of the Taliban in Kabul, TTP seems to have regained strength and has ramped up its attacks, many of which have taken place in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

“Following the Taliban’s rise to power in Afghanistan in 2021, militants started appearing again in Swat and other border areas,” said Swat Valley resident Babak. “Aggrieved by the government response toward the militants, the citizens of Swat gathered and a movement started against the new wave of militancy by the name of ‘Swat Citizens Uprising.’ The citizens at large came out from their houses and chanted slogans against the militants and their facilitators.”

Friend or foe next door?

Most of TTP’s leadership operate from Afghanistan, which shares a 2,640-km border with Pakistan. Its members, however, are mostly Pakistanis. Islamabad has accused the Afghan Taliban of coddling TTP inside Afghanistan and enabling it to launch its attacks in Pakistan. Taliban Spokesperson Zabiullah Mujahid, however, recently stated that the accusations were “baseless and provocative.”

It was the Afghan Taliban that had brokered the ceasefire between Pakistani forces and TTP last year. Pakistan had been supportive of the Afghan Taliban for years, betting that doing so would help Islamabad stand up to Western powers and strengthen its hand in dealing with its own insurgents.

But many now say that was a gross miscalculation on the part of Islamabad. There are even those who believe that the increasing militancy across Pakistan is due largely to Islamabad’s support of the Afghan Taliban.

“The Pakistani policy of imposing Talibanization in Afghanistan is mainly responsible for it because the factories producing Taliban are in Pakistan and there is no real difference between Afghan Taliban and the TTP,” asserted Khattak, a former senator. “Dismantling the Taliban can lead to a real and sustainable solution. Anything short of that will be running after the symptoms without addressing the root cause.”

“But,” he added, “the complicating factor is the Western support for this policy. The (2020) Doha deal between the U.S. and Taliban midwifed by Pakistani generals is proof of that. It’s part of the struggle among big powers over Eurasian heartland.”

“It’s going to be a War on Terror II of sorts,” Khattak said. “And lest we forget, Pakistan will need money for fighting it.”

Kugelman, for his part, said, “The Afghan Taliban has been quite consistent in its position that it will facilitate talks between the TTP and Pakistani state. But despite assurances of curbing regional terror threats on its soil, the Afghan Taliban is not about to launch operations against its TTP ally. If Pakistan launches counterterrorism operations on Afghan soil, the Taliban will become even more inflexible and unwilling to help Pakistan in ways it wants.”

He is convinced that it is no longer a question of whether or not Islamabad should launch a counter-offensive against TTP, but of how it should do it. “Allocating funds shouldn’t be a major problem, given that the Army will find a way to secure them,” said Kugelman. “But important decisions would have to be made about what type of operation — in terms of tactics and weaponry — and geographic scope. If the idea is to take the operation into Afghanistan, that will be a more risky and complex operation than one limited to Pakistan.”

Babak meanwhile said that while there seems to be little or no TTP presence right now in Swat Valley, the people there have “hidden fears.” Still, he said, “We want peace at any cost. We are united against militancy. Nobody will be allowed to disrupt peace in the area.”◉