|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A

s a school boy, Hiroyaki Sono had played for hours with friends on Amami Oshima island’s golden beach that was just a few meters from his home. “Spending carefree days by the blue sea was our deepest pleasure and reason for hope,” he says.

Today, however, Sono, now 86, is among those fighting to preserve that emotional link — and more. For the past decade or so, Sono and other island residents have been challenging local politicians over public works projects that, the residents say, destroy Amami Oshima’s unique environment.

Currently, Sono and his friends are trying to save Katoku, a beautiful beach front on the island, from a massive seawall costing US$5.5 million. Planned in 2013 by local assemblymen to protect the island from typhoons, the seawall will replace the natural sand dune and cover most of the beach.

“Our distinct dialect and culture are closely entwined with the surrounding landscape that we view as sacred,” says Sono, a former middle-school teacher who is also a veteran environmental activist. “Destroying nature means destroying our right to our identity.”

Jean Marc Takagi, another Amami Oshima resident, comments, “I am not an activist, but after arriving in Katoku after searching for years for a pristine beach in Japan with less unsightly concrete, I realized the crucial role of nature in preserving local identity as well as psychological stability in people. Destroying this beach is another terrible blow to this important function.”

With a population of 75,000, Amami Oshima is a subtropical island in the southern part of Japan. The biggest island in the Amami archipelago, it is located roughly 1,300 kms south of Tokyo. It is a strategic site for Japan’s Self Defense Forces that are being beefed up at present in the midst of China’s expansion of its military might in Asia.

In the 15th century, Amami Oshima became a part of the Ryukyu Kingdom of Okinawa and was annexed into mainland Japan 200 years later. It became a World Heritage Site in 2021, in recognition of its unique biodiversity.

But with much of the island`s younger generation having left for larger cities in the mainland, the task of protecting the vanishing local culture — and ecology — has been left to elders like Sono. According to Sono, concrete structures such as hotels, roads, and seawalls built by local councilors to promote the island over the years have eroded the local biodiversity, causing great emotional pain to the residents.

The current protest movement against the seawall in Katoku has gained attention even outside of Japan. More than 30,000 people have signed a petition to stop the structure’s construction, while a crowdfunding scheme has raised more than JPY 2 million (US$15,000) to support a lawsuit filed in 2019 against Kagoshima local government that governs the island. The court is expected to hand down its decision this February.

More than a potential eyesore

Katoku beach is alongside a natural river estuary that flows into the sea. It belongs to an isolated hamlet on the southeastern side of the island and is one of the last pristine areas on Amami Oshima that is without concrete structures.

Marine science expert Mariko Abe of the Nature Conservation Society of Japan (NCS-J) notes that Katoku beach comprises special sand dunes that are not coral-based. “The place, therefore, represents a unique ecology that hosts hundreds of rare species with life cycles that depend on the sea,” she says. “The (beach) must be preserved.”

Among its natural inhabitants, in fact, is the leatherback sea turtle species that lays eggs in Katoku. The species is already on the Red List of Threatened Species of the International Union for Conservation Union. Experts say that without access to the sea and narrower beach fronts, the nesting patterns of the turtle’s local population will be drastically altered.

Critics have also argued that the seawall, if built, will gradually erode the beach front as a result of rising sea levels and greatly endanger the survival of the pristine landscape. Consequently, they say, it will affect the lives of Amami Oshima residents.

For sure, the protests have had some impact, and have forced strategic changes in the seawall plans. In 2017, for example, a plan to divert the river was discontinued. Two years later, the length of the seawall was rescaled to 180 meters, down from 530 meters.

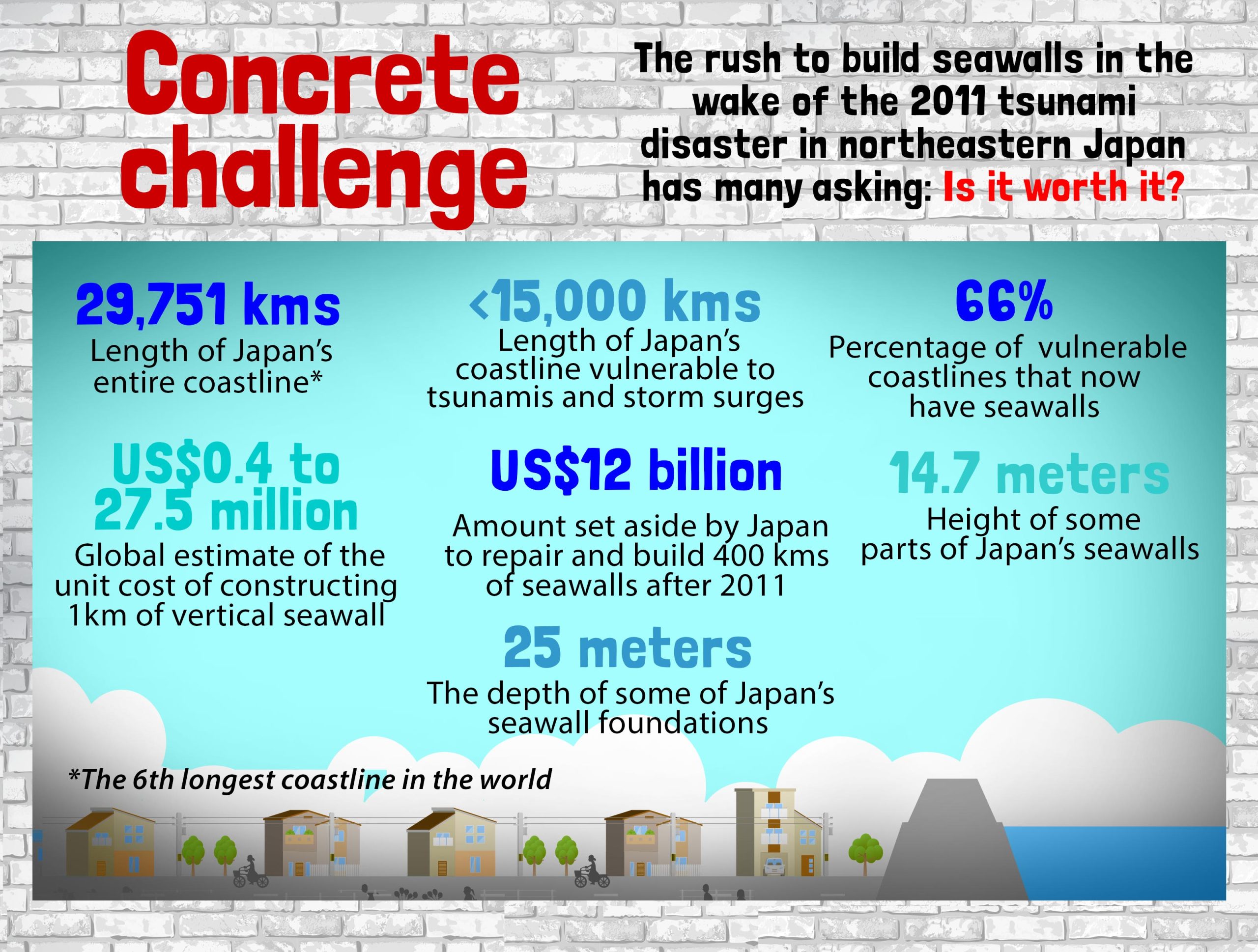

But the residents are up against the national government, which is supported by local politicians. The planned seawall, after all, is part of a decades-long nationwide disaster-prevention policy to protect local populations from tsunamis. According to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism website, the Japanese coastline in need of protection runs to around 15,000 kms, out of which 66 percent now have seawalls.

Intensified seawall-building

Since the massive earthquake and tsunami hit Japan’s northeast coast on March 11, 2011 and took more than 15,000 lives and left at least 450,000 people homeless, seawalls as disaster-risk reduction projects have taken a new impetus in the country. Critics say, however, that seawall proponents ignore the fact that the structures effectively block ocean views and interfere with the natural ecology. They have also proved expensive to maintain.

Some seawall critics have pointed out as well that the structures, however high they are, are no match for tsunamis. But officials defend the costly seawalls as crucial in buying people time to escape from the deadly waves. In Tohoku, which bore the brunt of the devastation caused by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, more than 430 kms of its coast facing the Pacific Ocean are lined with seawalls, some towering as high as 15 meters.

In Amami Oshima, local politicians insist that massive public projects such as seawalls benefit the people, partly by providing jobs. Indeed, the 1954 Special Measure Law for the Reconstruction of the Amami Islands that paved the way for new infrastructure passed on the argument that it would narrow the local income gap with the mainland.

To Abe, the ongoing struggle of Katoku conservationists to prevent the seawall’s construction is yet another heartbreaking illustration that, in Japan, material affluence pushed by conservative politicians takes priority over local ecology.

“It’s an uphill task to convince elderly policy makers who view Japan’s postwar economic growth model as critical to the nation,” she says. “Intense civic pressure results in (just) piecemeal changes because the preservation of the environment as a right of the people is still a nascent concept in Japan.”

Indications are that public opinion in Japan is turning against more seawalls, with more domestic media reporting on pushbacks by the people. In a March 2021 Asahi Shimbun article, for instance, Yorio Takahasi, a resident of a seaside community in Ogatsu, Ishinomaki City, was quoted as saying that a new seawall “killed” his town.

Ogatsu is among the places where protests against seawalls went nowhere. It started building a new one in 2016 to replace the previous seawall that was destroyed by the 2011 tsunami. Takahashi, who was a community leader there and among the majority of residents opposed to the structure, ended up moving elsewhere. To him, seawalls give a false sense of security while completely cutting off residents from the ocean.

Tohru Nakashizuka, president of the Forest Research and Management Organization, says, “The only way to fight back is to keep raising awareness among people of the importance of ecology as a human right.”

Alternative protection

Many Amami Oshima residents are doing even more than that. In 2015, Takagi and some of his neighbors set up the Association for the Conservation of Amami`s Forests, Rivers and Coastal Ecosystems, which focuses on alternative protection from typhoons.

A French national whose mother is Japanese, Takagi, along with the rest of his group, has been working steadily to revive the natural Pandanus forest that had lined Katoku beach but was damaged during a major 2014 October typhoon. Takagi says that past infrastructure built by public money has disrupted the natural course of the river, resulting in the disappearance of the naturally occurring sandbars that had protected the coastline from wave action.

Subsequent typhoons had sent massive waves to the Katoku beach shore and caused the erosion of natural vegetation. Yet, measurements taken by NCS-J and local volunteers between 2014 and 2017 revealed that the width of the shoreline has expanded naturally as sandy beaches do — from 40 meters to 100 meters, the widest it had been in 10 years.

To raise awareness about protecting Katoku beach, residents have been holding weekly sit-ins, as well as public seminars and education campaigns. Meanwhile, regular standoffs with bulldozers continue, which cause tension and frustration among the residents. According to Takagi, the police don’t do much to protect demonstrators. “It is not easy convincing the locals who do not want to speak out and face the risk of losing their jobs,” he says.

In the meantime, Sono and some of his friends are also reviving the language their grandparents had used but which is now largely forgotten. Says Sono: “The fight to save our language is closely associated with my activism against the destruction of the environment. Both aspects relate to preserving our personal identity and a human right.”◉