|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

E

very day, from dawn to way past dusk, waste collectors ride their bikes up and down the streets of Hanoi in search of materials that they can sell. Among them is Lương Thị Hoa, whose weather-beaten face shows all the three decades she has been at this job. She says that she has seen and heard it all, and has been called all sorts of names. Just recently, while she was calling out for anyone with scraps, a voice shouted back, “Đồng nát, get the hell out of here!”

Đồng nát literally means broken copper, but now people understand it to mean “scavenging.” Hoa and her colleagues are often called the names of the stuff that they buy and sell: đồng nát, ve chai (bottles), sắt nhựa (iron and plastic) — anything that can be reused and resold, really — and phế liệu (waste). The name-calling is obviously meant to put the waste collectors down, but the work that they do is crucial to the well-being of the communities in which they operate.

Informal waste collectors like the 50-year-old Hoa are actually climate-change frontliners. In countries that have no official recycling mechanism, they are usually in charge of the collection, categorization, and recycling of a significant volume of trash that would otherwise clog waterways or add to waste pollution. In a 2021 report on what it calls “informal recyclers,” the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA) even describes people like Hoa as the driving force toward a zero-waste world.

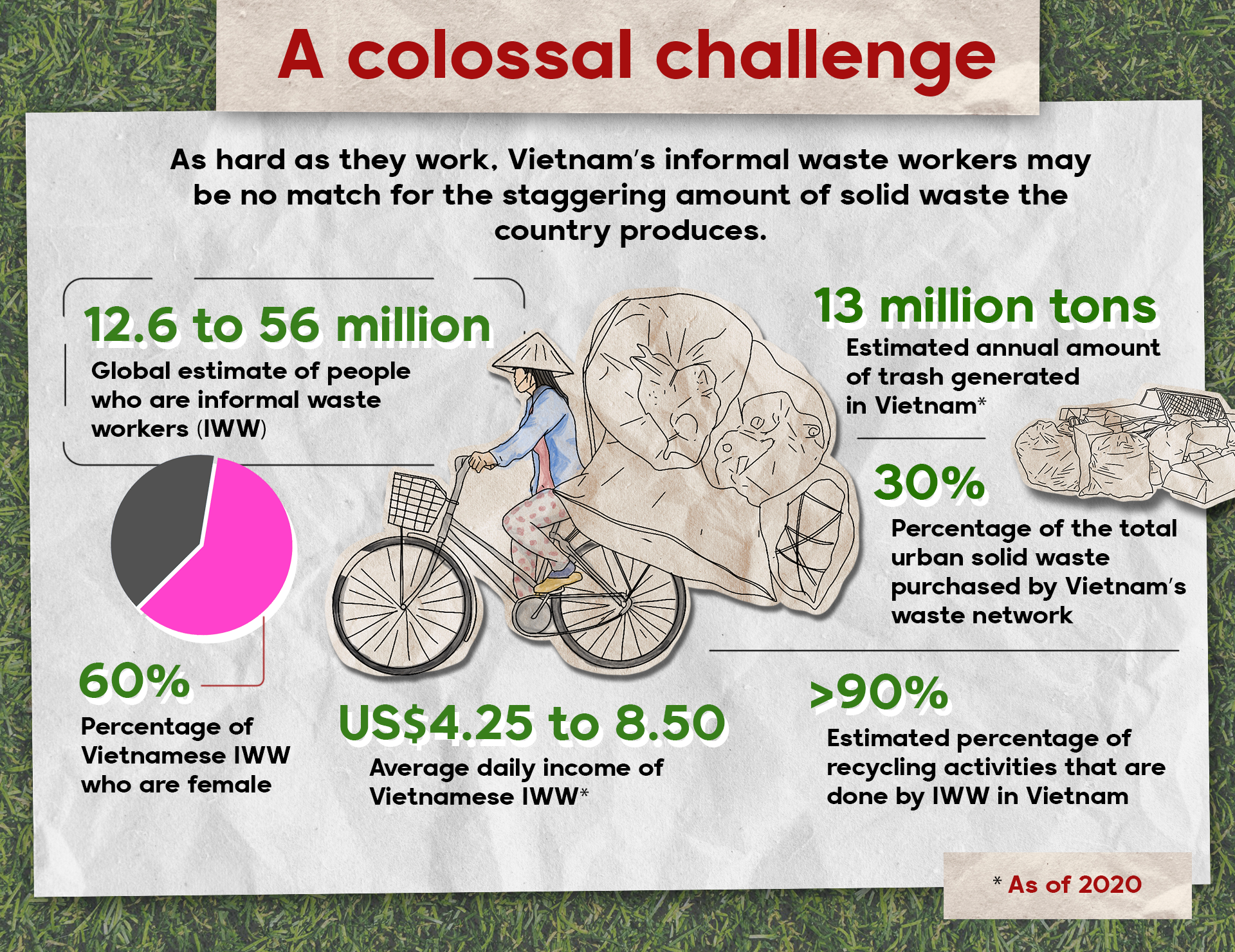

In Vietnam, these workers purchase 30% of waste in cities. More than 90% of recycling activities in the country are also carried out by informal workers, mostly in the so-called “craft villages,” where people do so to generate supplementary income aside from what they earn from agricultural and handicraft work.

Hoàng Đức Vượng, board chairperson of Vietcycle, a Hanoi-based corporation that deals with plastic waste and supports waste workers, estimates that there are about two to three million waste workers (including “diverse types of workers, namely waste pickers, shippers, and so on”) across Vietnam. GAIA, meanwhile, says that the number of people working in the informal recycling sector worldwide is anywhere between 12.6 million and 56 million.

Unrecognized part of the cycle

Since 2009, waste pickers have been more visible and vocal on issues related to climate change. Vietnam has even become a member of the International Alliance of Waste Pickers to enhance inclusion and visibility of these workers in formal waste-management systems. Nevertheless, according to Hoàng, climate projects in Vietnam are just beginning to include them.

“There need to be more endeavors to involve informal waste collectors,” says Hoàng. “(So far), they only focus on extracting recyclable materials for sale.”

A cycle of informal waste recycling involves collection and categorization of scrap by informal pickers, who then sell what they have segregated to collection centers. These centers in turn sort out the waste again and transport it to consolidation hubs, and then finally to professional recyclers. According to GAIA, the work done by informal waste collectors translates into savings in the waste sector in the form of diminished transportation and disposal costs, incomes from sale of recyclables, and reduced collection costs.

Despite their important role in the waste-management system, informal waste collectors are often considered unemployed or underemployed. The lack of understanding of their work has also led to their being usually subjected to discrimination and ostracism. In Vietnam, the popular view of waste workers is mostly negative: sticky-fingered, ill-educated, inferior, and dirty.

Hoa says many people think that way because waste collectors like her look and sound nhà quê, or from the countryside. For sure, many of Vietnam’s urban waste collectors are from neighboring towns. Many of them are also women; Vietnam’s waste-recycling system, in fact, has a workforce that is 60% female, despite the work being often physically challenging. Hoa and her colleagues say they carry up to 30 kg on their bikes at a time and on average travel 20 kms per day, rain or shine.

Hoa indicates that it is probably best that few men take on their work because, she says, women are better at enduring petty humiliation while men tend to have big egos.

“If men were humiliated by strangers,” she says, “they might get into a fight and get into trouble with the police.”

Vietcycle chairperson Hoàng, for his part, observes that most waste pickers are women from economically challenged families. He remarks, “Oftentimes, when men are not able to serve as breadwinners of their families, women are more likely to self-sacrifice and juggle multiple jobs in order to make ends meet. This is pretty much our tradition.”

Starting from copper scraps

According to the 2021 book Scavengers and Scavenging in Hanoi: Visibility in the Community by Nguyễn Thái Huyền of Hanoi Architectural University, Vietnam’s scavenging industry first took root in Nôm village, Đại Đồng Commune, in the northern province of Hưng Yên. Women in the village, which was well known for its bronze-casting industry, had to collect or purchase shredded copper and sell them to foundries to support their husbands’ education. Soon, scrap-selling became a popular occupation not just among the women, but also among those who were no longer interested in farm or bronze work.

For some of the current waste collectors in Hanoi, it was the 22nd edition of the Southeast Asian Games that drove them toward such an occupation. Vietnam was the host for the 2003 SEA Games; part of the efforts of Hanoi authorities to clean up the capital for the regional sports event was to ban street vendors in several places across the city.

Nguyễn Thị Mây was then a street hawker; she saw her livelihood practically disappear. But Mây, who is from Hà Nam province, recalls, “I did not have time to cry over my loss. I just started to (work as a waste picker) right away.”

Trần Thị Tuy, from Hải Dương province, had a similar experience. With just a small capital, a pair of gloves, and a mask, Tuy started collecting waste in Hanoi in 2003 because of the impact of the SEA Games on her former livelihood. The next year, she moved to Hồ Chi Minh City, but kept on collecting waste there.

Mây, Hoa, and Tuy have yet to receive training on technical aspects of waste collection, sorting, and recycling. More experienced waste collectors taught them how to collect and categorize discarded items by hand. But they still have a lot to learn about many recyclable materials, resulting in them being tricked into buying waste of no economic value.

Once, Mây bought a water pump, thinking it was solid copper, which meant she could resell it at a nice profit. She recounts, “When I arrived at the waste depot, the owner told me that it was aluminum and paid me much less than the amount I had purchased. I took a big loss.”

Mây now always brings a magnet with her to check whether a given item is real copper or merely copper-plated.

Very long workdays

For Mây, a typical productive workday starts at 4 a.m. and ends at 10 at night, or whenever she is done with delivering the final pile of waste to a depot. Mây has strategized collecting waste at 5 a.m. near bars and restaurants, when these places often start to throw away their soft drink cans from the previous nights. She says that 6-7 p.m. is also a good time for waste collecting, as this is when families begin throwing away their household trash.

Mây often looks for four major waste categories that can potentially sell well: paper and cartons, plastic, aluminum, and iron. On average, she earns VND 5 million to VND 6 million (US$212 to US$253) per month, roughly equal to the minimum monthly wage of an entry-level civil servant in Hanoi.

“Being a metal scraper is better than a street vendor,” declares Mây. “I can surely earn something per day. I do not have to carry fruits all the way from my hometown to Hanoi and then perhaps carry decayed ones back.”

Hoa and Tuy, while selectively buying recyclable waste, collect everything given for free. In general, household waste is not separated at the source. The two waste collectors say that it is hard for them to determine the economic value of discarded items at first glance, so they just take everything they can. Plus, neither wants to stay long in an alley or neighborhood for fear of being chased away.

“Some people pity me, even though I offer to buy and pay,” Hoa says. But she stresses, “I am not asking for any favor.”

Trần Phong, a young professional from Ho Chi Minh City, says that in the past, he would sell waste paper to waste pickers to earn some pocket money. But since he became more aware of recycling and the work women like Hoa, Tuy, and Mây do, he now gives his recyclable waste for free as a way to support these women.

“Seeing them carrying dozens of kilos (of materials), I cannot bring myself to charge them for things I might not need,” says Phong.

Fluctuating prices

Scrap prices depend on the type of waste, as well as the market. Timing also makes a difference.

“Last year, one kilogram of carton was worth VND 4,000 per kilo (US$0.16),” says Mây. “But this year, it is only VND 2,000 (US$0.08). The waste depot owner told me that China no longer collects these materials. I am not clear (why).”

Yet Mây, like Hoa and Tuy, seldom questions fluctuations in scrap prices. While waste depots have been mushrooming across major cities, the three women say they cannot sell their items to just anyone.

“I only sell to regular buyers at good prices,” says Tuy, even though she is under pressure to sell everything she has collected by the end of each day; her landlady does not allow her to store waste of any kind in her room.

Many times, waste collectors cannot afford to bargain with their buyers. Hoa says, “From time to time, I am too tired to bring back the trash home. So I have to sell at whatever price they offer.”

This is even though the prices do not factor in the women’s physical labor. Mây says that there was even one time when she had to carry 20 kg of scrap from the fifth floor and all the way down. “Then,” she says, “I realized that I could not sell it.”

There are also times when there are slim pickings. On the first days of each lunar month, for instance, people avoid throwing away stuff due to religious beliefs. Waste collectors are also not allowed to ride a bike on pedestrian streets during weekends; neither can they carry scraps with just their hands due to the belief that doing so would invite criticism from security guards.

And for all the years they have had in waste collecting, the three women agree that the work is getting harder — especially in the last three years. Tuy in particular says that she redoubled her efforts this past autumn and winter to make up for the “COVID time” when she could not work, as well as during the summer when it was so hard to go around the capital in scorching heat.

These days, too, they are competing not only with younger waste collectors, who they believe are more knowledgeable about electronic recyclables, but also with fellow migrants. Says Tuy: “More and more women from my village have left farming and started picking waste in Hanoi.”

Mây, though, still considers herself a lot luckier than her husband, who is a cyclo driver in Hanoi. “I might not earn the same every month,” she says, “but I will never starve with this job because people always have something to throw away.”◉