|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

I

n some countries, the story of two white-collar young men deciding to open a food stall may be taken as yet another tale of the strong pull of the entrepreneurial spirit. Yet when a video was uploaded of friends Mohammad Iqbal Itoo and Aqib Hamid Dar tending their tea truck in India-administered Kashmir, it went viral and led to discussions about the rising unemployment in the valley — and the rest of the country.

Itoo, 40, is a Master of Education and a Master of Philosophy in Environmental Science. He has worked as a contractual lecturer and teacher trainer for some 10 years now in different educational institutions in Kashmir. His friend Dar, 27, is pursuing a Ph.D. in mathematics at Rabindranath Tagore University in Madha Pradesh.

Dar, like Itoo, had looked forward to landing a job and having a long-term career once he finished his studies. Earlier this year, however, he and Itoo put up a tea truck in their hometown in South Kashmir, naming their modest venture “Chai Daam (A Sip of Tea).”

“When I saw my friend, Itoo, struggling for a permanent job despite having sufficient degrees and experience, I decided to jump into having a small business,” explains Dar as he serves his customers. “The government has failed to provide jobs to educated youths in Kashmir.”

Kashmir has no monopoly on rising unemployment in India. In fact, the country has been struggling with unemployment for years — and even before the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been blamed for the current economic crisis that in turn has led to increased joblessness. Between 2017 and 2018, government data even reveal that the country’s unemployment data reached a four-decade high of 6.1%. These days, India’s unemployment rate is at a 45-year high, touching 8.3%.

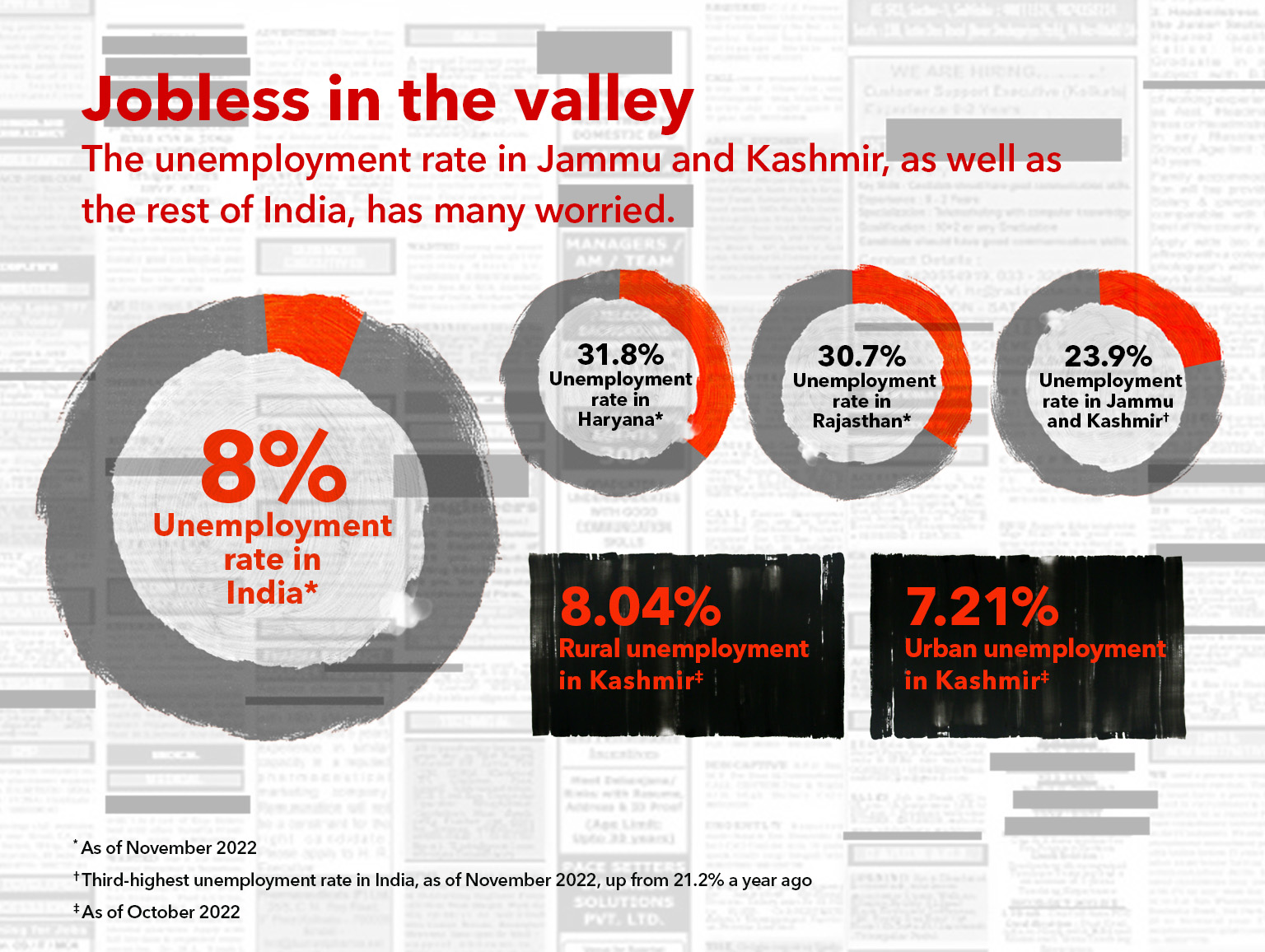

In Kashmir, the unemployment rate was 9% in mid-2018. In November this year, it was at 23.9%. According to the Mumbai-based think tank Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, Kashmir currently has the third-highest unemployment rate in the country, after Haryana (31.8%) and Rajasthan (30.7%).

Promises, promises

In Haryana, the unemployment crisis is due mainly to the erratic monsoon season that disrupted agriculture activities, consumer demands amid rising inflation, and industries turning more “labor efficient.” In Rajasthan, the slow growth in the manufacturing sector has caused more joblessness in the state.

Along with Kashmir, both Haryana and Rajasthan also have pandemic-related reasons for their high numbers of jobless people. Kashmir, however, has the dubious distinction of suffering a clampdown and a communications blackout even before the coronavirus began spreading across the globe in early 2020. Adding more salt to Kashmir’s many wounds, the central government has yet to make good on its promise to Jammu and Kashmir to deliver a revitalized economy — and therefore more job opportunities — to the region after the Aug. 5, 2019 abrogation of its semi-autonomy.

Just two days after that 2019 decision, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had promised the nation, and especially the people of Kashmir, that the historic act would usher in a new dawn in the region and help in the development of opportunities for the youth there.

Explaining his plan, Modi said that bringing Jammu and Kashmir under the central government’s rule as federal Union Territories would promote private investments in the region, as well as improve employment opportunities there. He also assured Kashmiris in particular that there would be thousands of state job vacancies in the valley that would be filled in a transparent and fast-tracked manner.

Alongside Modi, Science and Technology Minister and ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) stalwart Dr. Jitendra Singh, who is from Jammu, also consistently promised youths in the valley more jobs.

And yet, observers say, the words uttered by Modi and the rest of the BJP are still waiting to be translated into action. Comments a Kashmir-based political analyst who declines to be named: “BJP’s promises turned out to be a farce on the ground in Kashmir. The youth of our valley has been pushed to an edge where there are limited options for survival.”

Take Junaid, who completed his master’s degree in technology in 2017. He says that he has sat in a few government job examinations but didn’t get a post because of the tight competition coming from ever-increasing numbers of jobseekers.

“For a few vacant posts advertised by the government, tens of thousands of youth apply and appear in the government-employment examinations,” says Junaid, who wants to go by his first name only. “It has become very difficult to get a job in Kashmir because of fewer opportunities.”

One lockdown after another

The government is one of the three main — if not the top — employers in the Union Territory. The tourism and handicrafts sectors are the other big employers in Kashmir, but when the clampdowns began, jobs dried up in those fields as well.

“Unlike other places of the world where pandemic lockdowns had slowed down the economy, Kashmir had to bear the major brunt of the pandemic shock,” says a Kashmir-based scholar. “The entire valley was put under strict clampdown and communications blackout for six months just before the pandemic hit the world. That has caused more damage to Kashmir’s economy and impacted employment.”

In January 2020, the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industries calculated that the extended clampdown and internet blockade had cost the valley’s economy about INR 180 billion (US$2.4 billion). Media reports quoted the Chamber as saying that the general trade sector was the worst hit, where about 120,000 people lost their jobs in four months. The Chamber also said that 74,000 jobs were lost in the tourism sector and another 70,000 in the handicrafts industry, including the famous Kashmiri carpetmaking.

Khalid Ahmad Bhat had just gotten a job in a hotel in the famous tourist destination of Pahalgam in Kashmir when the region was stripped of its limited autonomy. Recalls Bhat: “A few days after the clampdown was put in place, I was asked by my owner to temporarily leave the job. He told me I would be asked to resume my job once the situation would get normal.”

“However,” he says, “when the clampdown stretched for six months, I didn’t get my job back.”

Bhat survived by working as a laborer at different construction sites. He eventually landed a job at another hotel. But he says that he has yet to have enough income to meet all his daily needs. “My salary is so low that I can’t even manage my basic requirements,” says Bhat.

Just as Kashmir was emerging from its six-month clampdown, the central government imposed a lockdown in March 2020 to combat the spread of the coronavirus. By the end of the first year of the pandemic, losses to the Kashmiri economy between August 2019 and December 2020 were at INR 500 billion (US$6.7 billion).

In early 2021, just as businesses were opening up, India yet again went into lockdown as the second wave of the pandemic hit the nation.

More promises despite unmet targets

“The current unemployment crisis in India is partly because of the pandemic,” concedes Mahtab Khan, an economics scholar based in Delhi. But then, he points out, “The lackadaisical attitude of the government toward the unemployment issue and some hasty decisions by the government has damaged the Indian economy even before the pandemic hit the country.”

In truth, after securing victory in the 2014 general elections, the Modi government had even launched the “Make in India” project, which sought to increase manufacturing jobs to 100 million by 2022. Remarks Khan: “We are nowhere near that target yet.”

In truth, after securing victory in the 2014 general elections, the Modi government had even launched the “Make in India” project, which sought to increase manufacturing jobs to 100 million by 2022. Remarks Khan: “We are nowhere near that target yet.”

Yet the promises still keep coming. Last April, during his first visit to Kashmir after the abrogation of its special status, Modi again promised that the youth of the Union Territory would not suffer the way their parents and grandparents had in the past. Focusing on the development in Kashmir, the central government began its mega outreach program in the Kashmir Valley this October. It announced that over 65 central ministers would visit all 20 districts of Jammu and Kashmir and review the status of the development projects, prepare a report on it, and then submit the report to the prime minister’s office and Ministry of Home Affairs.

Meanwhile, the administration in Kashmir says that recruitment for government positions is being done in a transparent and corruption-free manner. On Nov. 15, Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha also said that the government had provided direct means of livelihood to 30,000 youths including 12,000 girls from 2021 to 2022. Chairing the second Governing Body Meeting of Mission Youth at the civil secretariat in Srinagar, the summer capital of Kashmir, Sinha approved various schemes and plans that will focus on development and employment in the valley.

But Dar, the new tea truck owner, isn’t convinced that there would be jobs for people like him anytime soon. He has set his eyes on expanding the business he has started with his friend Itoo.

“I don’t have any hope of getting a good job even after completing my Ph.D.,” says Dar, while preparing yet another cup of tea for serving. “There are very few opportunities available for educated youth in Kashmir.”

Perennial jobseeker Junaid is thinking the same thing. “I am planning to take a loan from a bank and start my own business,” he says. “I have already crossed 30 years of age. I believe it unwise to wait for a job in Kashmir.”◉