|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

M

ass protests, or aragalaya, are no longer a daily affair in Sri Lanka. The demonstrations that helped oust a government a few months back are far from being over, though. Current President Ranil Wickremesinghe has even threatened to arrest those planning yet another aragalaya, but Sri Lankans reeling from the effects of a severe economic downturn may not be in the mood to heed his words.

Yet while the aragalaya reflect the breakdown of the relationship between Sri Lanka’s people and their leaders, the protests seemed to have opened an opportunity for dialogue between the majority Sinhalese and the minority Tamils. With the participation of people across class, caste, religion, and region, the aragalaya even raised hopes for reconciliation between the two communities that have generally had trouble getting along.

“A large section of Sinhala people have been indifferent toward the plight of Tamils as the latter were projected as an enemy of the country by successive central governments,” says Ceylon Teachers’ Union General Secretary Joseph Stalin, who has been a regular at aragalaya that began early this year.

But now, he says, “Sinhalas have realized that the suffering of Tamils has been ignored for too long.”

About 75% of Sri Lanka’s 23 million people are Sinhalese, most of whom are Buddhist. The Tamils meanwhile make up about 15% of the country’s population. Most Tamils are Hindus; a significant number are Muslim while there are also Christian Tamils.

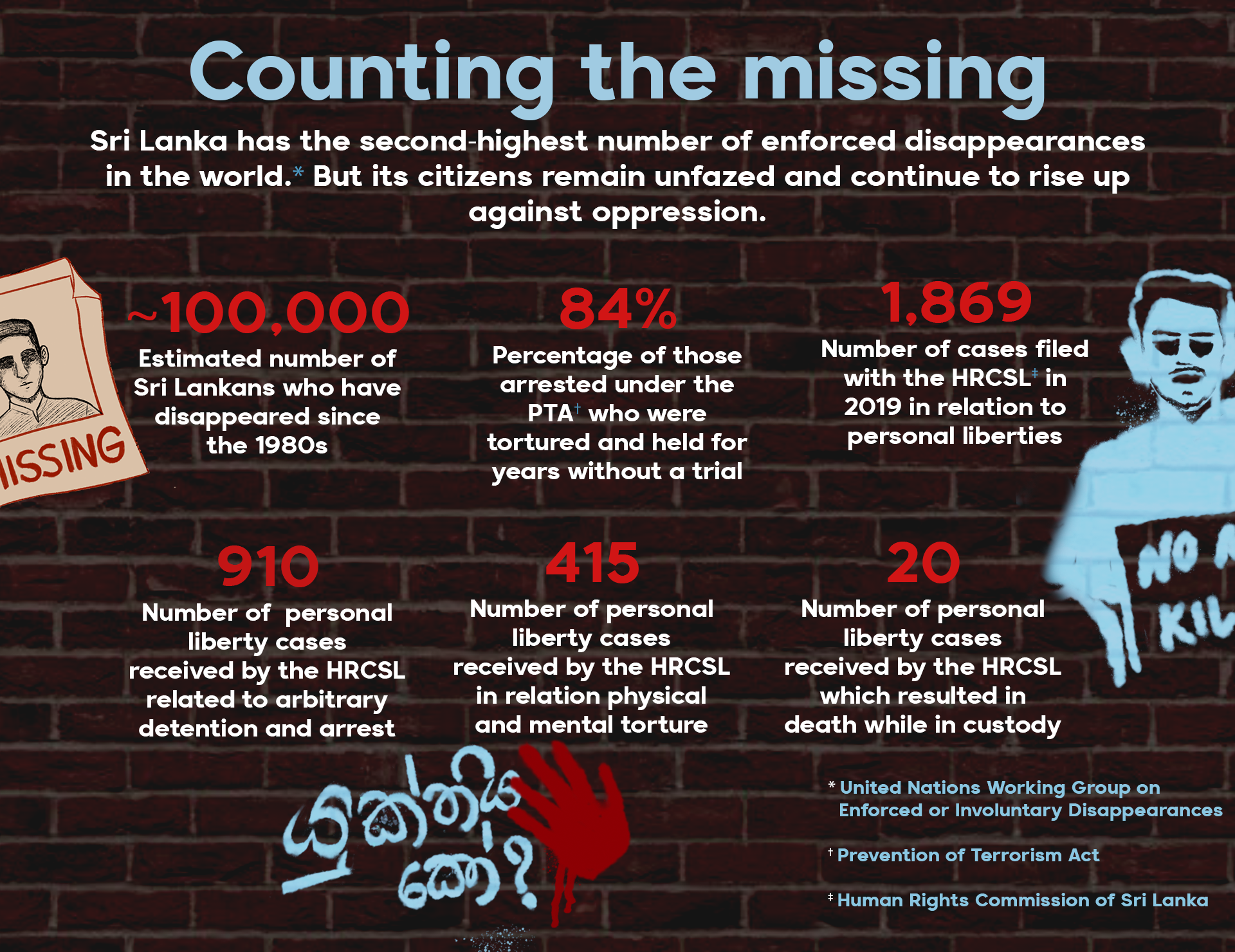

Between 1983 and 2009, parts of Sri Lanka became stages for savage warfare between the country’s military and the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). While the war raged, over 100,000 people — mostly Tamils — disappeared in Sri Lanka. For decades now, Tamils have been looking for their missing fathers, husbands, sons, and daughters. But the majority Sinhalese population barely paid any attention to their plight, with many saying simply that it was not their fight.

In fact, for the first time, Kulandaivel Sumitra Devi, a Tamil who has been looking for her husband who went missing in 2008, says that she is hopeful that the government may finally begin listening to people like her. She says that this is because a section of the Sinhalese population is finally standing by the side of Tamils.

“Since the Sinhalese activists have expressed their empathy toward us, we are hopeful that our pleas will be answered now,” says Sumitra Devi, 42, a resident of Ampara in Eastern Province. “Unfortunately, the Sinhalese people took more than three decades to stand by us, to hold our hands.”

Been there, done that

On Aug. 12, Sumitra Devi, along with hundreds of other victims of the civil war from northern and eastern provinces — the traditional Tamil homeland — gathered at Kilinochchi, about 100 km from the Northern Province’s capital Jaffna, demanding justice. They were joined by over 35 Sinhala students, activists, and civil society members, who had traveled about 350 km from the country’s capital Colombo to express solidarity with them.

Earlier, on May 18, hundreds of citizens including Sinhalese Buddhists gathered at Colombo’s Galle Face Green, an open public space overlooking the Indian Ocean. The site had been the center point of aragalaya between April and July this year. The May gathering, however, was to mourn the 2009 killings of Tamil civilians in the last battle the army had fought with LTTE guerrillas at Mullivaikkal in Northern Province. For more than a decade, Colombo had celebrated the occasion as “Victory Day,” to hail the Sri Lankan army’s win in the war.

Earlier, on May 18, hundreds of citizens including Sinhalese Buddhists gathered at Colombo’s Galle Face Green, an open public space overlooking the Indian Ocean. The site had been the center point of aragalaya between April and July this year. The May gathering, however, was to mourn the 2009 killings of Tamil civilians in the last battle the army had fought with LTTE guerrillas at Mullivaikkal in Northern Province. For more than a decade, Colombo had celebrated the occasion as “Victory Day,” to hail the Sri Lankan army’s win in the war.

Some Tamils believe that the current nationwide economic crisis that led to severe power cuts and rising food and fuel prices has been an opportunity for people living in the west and south of the country to finally understand what Tamils had gone through during the civil war.

Ampara resident Devasahayam Ranjana, 69, says that people in the north faced power outages and economic embargoes on many consumer goods including diesel fuel, petrol, fertilizer, pesticides, and medical products during the war. She says that they also faced restrictions on fishing, imposed by the Sri Lankan government in the 1990s.

“Economic crisis is not new to us, we have seen it all,” says Ranjana, whose husband and eldest son have been missing since 2009.

Similarly, enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrests, and heavy deployment of military personnel in civilian areas — now routine in Colombo in the south ever since Wickremesinghe was elected president in July — have been fairly common in the north and east.

Sushila Devi, a resident of Batticaloa in the east, recounts how her 18-year-old son was dragged out of a bus by the Sri Lankan army personnel in 2007 while they were traveling from Trincomalee to their hometown. She says that she ran pleading for help behind the army vehicle for about 100 meters while her son, who was in the vehicle, held tightly onto the gold chain around her neck. But a soldier kicked her hard on the stomach, forcing her son to let go of her necklace. The vehicle sped away, and she was left lying on the street, devastated and in pain.

“The army never gave me my son back,” says Sushila Devi, who has even approached the International Committee of the Red Cross, seeking justice. “I have the right to know if he is alive or dead.”

The army gave no answers to Sumitra Devi either — even after she found her husband’s identity card with one of the army personnel deployed at the checkpoint near their family’s farm, just days after he went missing. She remarks, “The army never realizes that they are accountable to us.”

Detained, disappeared, dead

In 2015, former Sri Lankan President Maithripala Sirisena proposed to establish a truth and reconciliation commission. But the United Nations at the time said that the country was “not yet ready or equipped” to conduct a “credible investigation” into suspected violations.

Human rights defender Ambika Satkunanathan says that up to now, the Sri Lankan government does not have complete data on the number of people who disappeared or were killed during the war.

Satkunanathan notes that some people were issued death certificates for their family members who were victims of enforced disappearances, and were also given paltry compensation by the government. Many were forced by the government to accept these death certificates, she says, adding, “Some accepted compensation because of their dire economic circumstances.”

Satkunanathan says that information on those who were killed or disappeared can be considered complete “only if there is no sense of fear among Tamils.”

Tamils, however, continue to live in fear. According to Amnesty International, the families of the disappeared allege harassment and intimidation by law enforcement officers through unannounced visits, intimidating phone calls, and surveillance. Additionally, says the international rights watchdog, the state security apparatus of late has begun approaching the judiciary to pre-emptively restrict the victims’ freedom to protest.

Sri Lankan police also still randomly book Tamils under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) for their alleged former association with the LTTE. Just last April 25, 10 Tamils who were arrested for holding a beach memorial for the civil-war Tamil dead were finally released after seven months in detention. Human Rights Watch also points to a 2020 report by the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka that said 84% of those arrested under PTA were tortured and that some have been held for as long as 10 years without trial.

“(A) Tamil Hindu priest, arrested in February 2000 for suspected involvement in an LTTE attack, was held pre-trial under the PTA until 2015 when he was convicted and sentenced to 300 years in prison,” the Human Rights Watch said in a 2022 report. The conviction, it continued, was based on a confession that the priest claimed was “obtained through repeated torture and recorded in a language he could not understand.”

Satkunanthan says that after the end of the war in 2009, many Tamils who were not LTTE combatants were detained at military-run rehabilitation centers, in contravention of international humanitarian law. Now the same oppressive system is being extended to target those who participate in aragalaya.

Shared oppression

Satkunanathan has filed a motion at the Supreme Court against a proposed Bureau of Rehabilitation Bill that will allow the detention of possibly any citizen, bypassing the judicial system, in rehabilitation centers. She describes the bill as inconsistent with the fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution of Sri Lanka that guarantee freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention, torture and ill-treatment, and discrimination.

For his part, Mahendran Thiruvarangan, a senior lecturer in English at the University of Jaffna, agrees with the observation that Sri Lankans living in the south are now becoming aware of the atrocities against the Tamils.

Yet, he cautions that the relationship between the Tamils in the north and east, and the Sinhalas in the south, may remain precarious. Thiruvarangan says that a protest rally was held by academics, trade unionists, and civil society groups in the north to show solidarity with those holding aragalaya. But an active Tamil nationalist lobby, which demands self-determination, discouraged the sympathy protests.

According to the academic, while the nationalist Tamils acknowledged that May 18 was observed by aragalaya protesters in Colombo, the nationalists had pointed out that there was no call for political justice for the genocide of Tamils or reconciliation.

One of the main bones of contention among Tamils in the northeast is that the Sri Lankan government has been taking over religious sites of Tamil Hindus and putting up Buddhist stupas and temples in the region. Recently, there were attempts to annex two Sinhala-majority villages in the Anuradhapura district in the North-Central province to the Tamil-majority Vavuniya district in the Northern Province.

Thiruvarangan also says that lands belonging to many Tamils displaced in the war have been acquired by the military over the years. He adds that the Sri Lankan government has also tried to give a Sinhala-Buddhist character to the territories in the north under the pretext of archaeological research.

For Sumitra Devi, these attempts to “take over” Tamil-dominated areas pose a big threat to their existence. She says, “Sinhalas must oppose these attempts if they really believe that it’s time to stand by us.”◉