|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

N

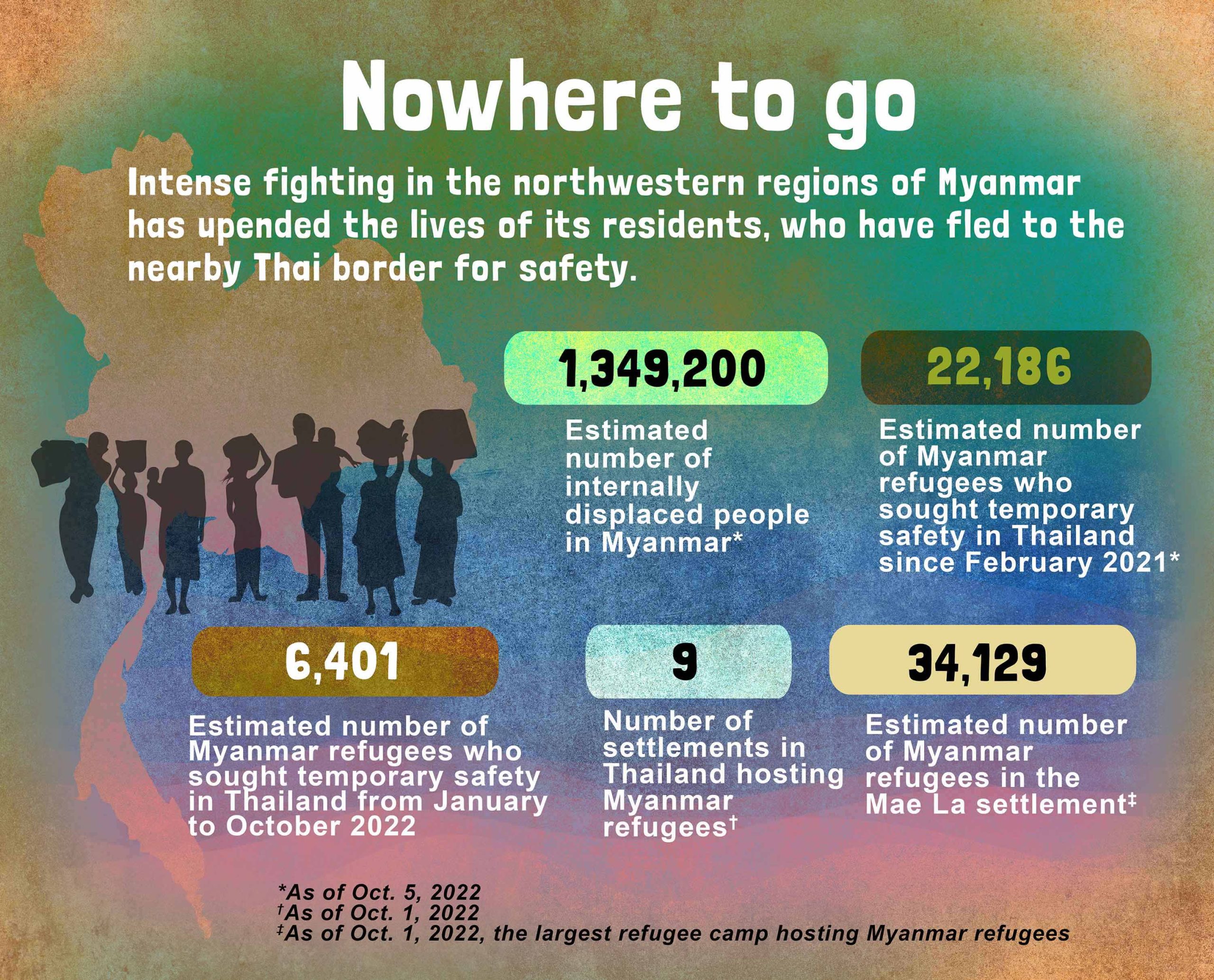

early two years after the military grabbed power in Myanmar, political turmoil, perpetuated through violence and crimes committed by the regime, continues to drive thousands of the country’s people into neighboring nations. More than one million civilians have been displaced since the coup in 2021, including some 45,500 who have been forced to flee Myanmar and are now in nearby countries such as India and Thailand.

Yet while those who fled across the border are now relatively safe, their nightmares are far from over. Those in Thailand, for example, have found themselves up against a very reluctant host that has no official policy on refugees and is not a signatory to any international conventions covering people in need of safe refuge. That means Thailand does not accept any international aid for refugees and is also not bound by any global agreements on them.

A January 2022 Bangkok Post editorial summarizes what is often in store for those seeking refuge in Thailand: “For state authorities, people who fled to Thailand from wars, violence, and persecution in their countries are treated as illegal aliens, liable to deportation at any moment. Meanwhile, the ‘displaced persons’ in border camps and asylum seekers outside routinely face hardship and hopelessness from systemic disregard.”

People from Myanmar know this too well. But they cross the border anyway because they have little choice. Even before the coup, many Myanmar citizens had been heading toward Thailand in droves to escape the seemingly endless fighting between their country’s ethnic armies and the military.

But the number of those fleeing to Thailand has escalated since February 2021. According to official Thai data, some 22,000 Burmese have fled to Thailand since the coup last year. Of this figure, more than 6,000 poured into Thailand between January and October 2022. As things turn from bad to worse in Myanmar, there is no doubt that thousands more will try to leave it and go next door to Thailand.

Thailand does offer shelter and some support to refugees, as well as letting displaced people apply for labor registration cards (pink cards). But those who want to work first have to secure papers, which can be difficult for people who fled with just whatever they had on at that moment. Moreover, many limitations and risks remain for those forced to cross the border into Thailand, while any aid or gesture of hospitality toward these people who are obviously in need seems to depend on the whims of local Thai authorities.

Arrests and deportation

Just this September, a group of students from Myanmar who had set up camp on the Thai side of the border was forced back by Thai authorities. The next month, more than 100 displaced Myanmar people were arrested because, local authorities said, they did not have proper papers and had crossed the border illegally. Says an undocumented political activist from Myanmar: “These days, we are too afraid to stand in front of the house as the Thai police are quite serious in searching and arresting (members of) the Myanmar communities, especially those who are here for political reasons.”

A nurse who was part of Myanmar’s Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), in fact, was chased by Thai police when she went to the local market in one of the Thai border towns. In another cast, the mother of a four-year-old drowned while trying to cross a river to escape arrest.

Fears of possible arrest and deportation only add to the constant worries of Myanmar citizens who are now in temporary camps in Thailand. But while there are some resources — albeit limited — for mental counseling and psychosocial support, these are not readily accessible to the refugees, and far less to those who consider themselves merely displaced. (Some rights activists define refugees as those seeking asylum and displaced people as those who are in need of temporary shelter and safety but intend to go back to Myanmar as soon as they can.)

Not surprisingly, many have to deal with the trauma from their experiences back in Myanmar, as well as their new fears in Thailand, on their own.

“When I heard that Myanmar displaced people had been arrested again, I got quite nervous and cried,” says one woman who had escaped to Thailand with her baby. “There are tens of nights I cannot sleep, thinking of what the future holds for my son, where to return, and when to go home.”

At the same time, she worries that she and her child could end up without food while they are in their temporary home. “I have nothing to sell, and I have no idea how I can earn money,” says the woman. “There are still many people who do not even have enough rice to eat.”

Still, there are those who prefer to look positively at their dismal circumstances. Says one 32-year-old political activist who admits he is in Thailand undocumented: “Experiencing challenges and difficulties enhance our resilience.”

“The brutal military regime has been hunting us, wherever we go,” the activist says. “Our emotional and physical security has been lost since February 2021. Though it is safer to live here, we keep working for anti-junta activities while we struggle to survive.”

Escaping mayhem

Thailand shares a 2,416 km border with Myanmar, which is why many people from Myanmar end up there whenever trouble at home forces them to seek safety elsewhere. Before the coup, Thailand already had some 90,000 Burmese refugees housed in camps. There are currently nine official camps for people from Myanmar in Thailand, but there are also several makeshift camps near the border on the Thai side.

Majority of those who fled Myanmar after February 2021 did so because of the junta’s crackdown on activists and CDM members, as well as due to increasing violence in their villages and towns. One CDM teacher tells Asia Democracy Chronicles that he decided to leave Myanmar after learning that his house had been sealed off for the crime of “opposition to the military regime.” At least that was all that was done to his home; according to the latest humanitarian update on Myanmar of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, more than 30,000 civilian properties have been burned or destroyed since the coup.

In a chilling report delivered by Acting UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Nada Al-Nashif before the UN Human Rights Council this September, she described what people in Myanmar have been through so far.

“Since February 2021,” said Al-Nashif, “at least 2,316 people (including at least 188 children) have been killed. Widespread fear and insecurity among the civilian population have forced over one million individuals … to leave their homes and now live in precarious conditions without access to food, medical assistance, and other basic services. The humanitarian crisis now brings fears of starvation, with the military largely denying humanitarian access, including recent orders to halt humanitarian operations in northern and central Rakhine State.”

“Over 15,607 people have been arrested with some 12,464 remaining in detention,” she continued. “The death toll of people in custody is steadily rising. At least 273 persons have died in formal detention settings, such as prisons, detention and interrogation centers, and police stations as well as at least 266 reported deaths following raids and arrests in villages, at least 40 of whom were reportedly killed with headshots.”

Many Myanmar citizens who are now in Thailand can attest to all these. Says one woman from Myanmar: “As my husband is an NLD party (National League for Democracy, which won the 2020 elections) member and activist, I and my two-year-old baby could not live in our own house, and we were forced to move to the houses of my relatives. The military came and searched the whole house soon after we left. We had nowhere to go, so we headed for the jungle area, controlled by nongovernment ethnic armed organizations. But since it was not easy for a baby to live there, we decided to cross the border and flee to Thailand to seek protection and a safe place for me and my baby.”

Blocking helping hands

Officially, Thailand’s lack of a policy on refugees means that nongovernment organizations and even UN agencies are not allowed to give aid directly to refugees and displaced people and have to course such through the Thai military. But some local and Burmese nonprofit organizations have managed to break through such barriers and have been extending whatever help they can to Myanmar citizens seeking refuge in Thailand.

The decades-old Mae Tao Clinic in Mae Sot, western Thailand, for instance, is still a key source of health care for those in the Thai and Myanmar border areas. Its menu of services covers, among others, reproductive health, malaria, eye and dental care, sexual health, and childcare.

Local civil society organizations and CDM health professionals are now also offering telehealth services and digital medical consulting platforms. There are the likes as well of the New Myanmar Foundation, which offers basic classes on sewing and hairdressing, as well as training in digital literacy in partnership with a local nongovernment organization, the Women Lead Resource Center, in Mae Sot. And in Chiang Mai, community-based organizations have held fundraising events for the refugees and displaced people from across the border, along with preparing and donating basic packs for them.

Many Thais understand that most of those who fled Myanmar would rather be in their home country if only it had peace. The Bangkok Post January 2022 editorial also noted: “Peace in Myanmar means peace in Thailand. The government should be more proactive to engineer peaceful co-existence in a culturally pluralistic Myanmar.”

The editorial was a reaction to the sudden influx of Karen villagers over the border due to yet another clash between ethnic Karen armed groups and the Myanmar military. “When peace is not yet at hand,” it said, “Thailand should adopt the Refugee Convention to welcome international assistance and create legal infrastructure to provide safety and rights to refugees and asylum seekers. It also must stop forcible returns of refugees and asylum seekers.” ◉