|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

One young woman was from a local family while the other was from Bengaluru, about 567 km south of Hyderabad, the capital of the Indian southern state of Telangana. Both women had gotten pregnant by accident and had no idea what options were available to them. That was why they separately contacted Hyderabad-based medic and public health professional Anusha Pilli, who helped them get medical abortions using a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol before their first trimesters ended.

Pilli, however, was struck by the two 20-something women’s lack of awareness about the options open to them, as well as what is allowed under India’s abortion law. After all, she notes, both were college graduates from middle-class families.

“It made me worry about how much worse the awareness of abortion and other reproductive health choices would be among women in rural India,” Pilli says.

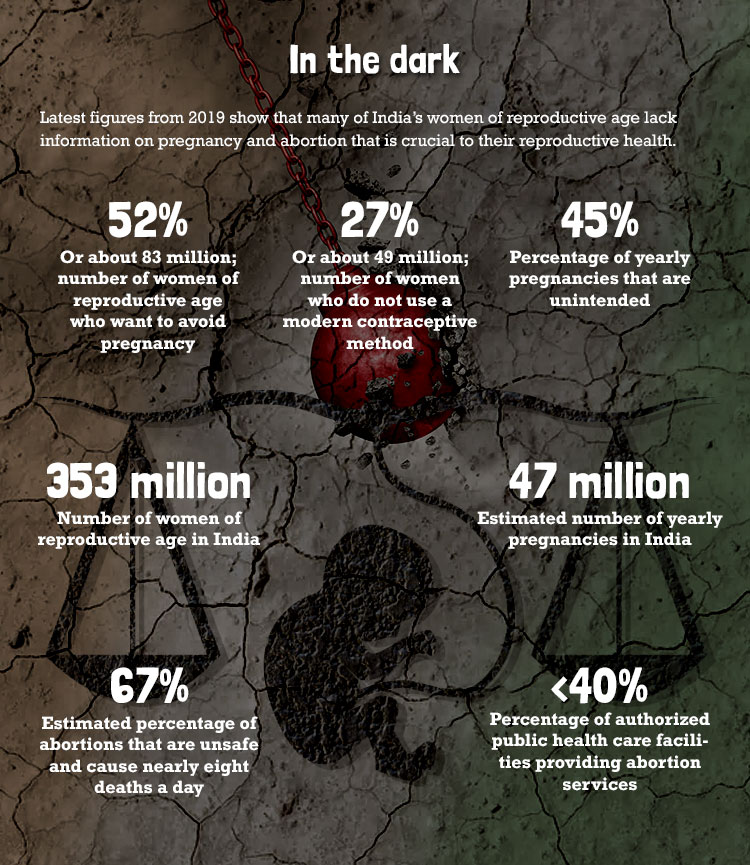

She has much reason to be concerned. The Guttmacher Institute, a research and policy organization committed to advancing sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) worldwide, says that in 2019, an estimated 52 percent of India’s 353 million women of reproductive age wanted to avoid pregnancy. Of these, 27 percent were not using a modern contraceptive method and were therefore considered as having an unmet need for modern contraception. Moreover, of the estimated 47 million pregnancies each year in India, 45 percent are unintended and women with unmet needs for modern contraception account for nearly nine out of every 10 unintended pregnancies.

It gets worse. The latest State of the World Population Report of the United Nations Population Fund reveals that an estimated 67 percent of abortions in India are unsafe and cause nearly eight deaths per day. In a country that for the past five decades has had a law allowing the termination of pregnancies on certain grounds, abortion remains the third leading cause of maternal deaths. Indeed, data and anecdotal evidence in India suggest that progressive abortion laws do not necessarily ease women’s access to SRHR services.

India’s experience is mirrored in nearby countries that also have legalized abortions, albeit with varying caveats. In a 2020 paper assessing legal abortion services in Nepal, Bangladesh, and six states in India, as well as post-abortion services in these three countries and Pakistan, data gathered by the Guttmacher Institute suggest that abortion laws cannot alone enable women to exercise their sexual and reproductive health rights. For instance, less than 40 percent of public sector health care facilities permitted to provide abortion services actually do so in India and Nepal. Bangladesh posted a “somewhat better” figure, 53 percent, says the Institute. More worrisome is the Institute’s finding that “the proportion of all abortions that are illegal ranges from 58 percent to almost 90 percent in the three countries where abortion is permitted under broad criteria.”

In India, the abortion rate per 1,000 women aged 15 to 44 is 47; it is 42 in Nepal and 29 in Bangladesh. By comparison, the global abortion rate is 39 per 1,000. In the United States, where the Supreme Court recently overturned the Roe v. Wade ruling that protected a person’s right to choose whether or not to have one’s pregnancy terminated, the rate is about 14.4.

The three A’s

The three biggest obstacles to women’s access to sexual and reproductive health services across India are the lack of awareness, access, and availability. In Bhadohi, a district in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, where 1.4 percent of second births are within 10 to 12 months of the first birth (the all-India figure is 1.6), many women continue to carry unintended and unwanted pregnancies to term as they do not know what else to do.

For example, Najma Begum, who is expecting her second child when her firstborn is not even a year old, says that she has neither access to nor knowledge of contraception and abortion. Adds the 24-year-old: “I don’t go out of my house alone. Even if I wanted to use contraception, I wouldn’t know where to get it and how to use it.”

Abortion is not a taboo among Hindus, who are the religious majority in India, but there is a fair amount of social disapproval attached to it. At the same time, while the central government has not imposed a limit on the number of children a family may have, some states provide incentives to couples who stop at two.

In 2019, Ipas Development Foundation undertook a survey to gauge the awareness of sexual and reproductive rights among young women in the states of Assam in the northeast and Madhya Pradesh in central India. The study found that only 22 percent were aware that abortion is legal in India, 62 percent believed that abortion was a sin, and three percent chose their own doctor. Rights and climate-action advocate Debanjana Choudhuri comments, “In the field, while we routinely see public health messaging on WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene) practices, menstrual hygiene, and education, we never see any awareness messaging around medical abortions and reproductive health.”

Access to abortion services, SRHR advocates say, has been greatly impeded by the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act of 1971 itself, as its strict definition of the abortion provider leaves many health professionals out of its ambit. Under the law, only the following can prescribe medical abortion drugs or perform surgical abortions: private obstetrician-gynecologists connected to hospitals with surgical facilities; obstetrician-gynecologists with six months of surgical experience; medics who have worked in a hospital in the practice of obstetrics and gynecology for at least a year; or those who have assisted a registered medical practitioner for pregnancy termination in at least 25 cases in a government-approved MTP hospital/training institution.

Such medical professionals are in short supply, however. Each of the 5,183 Community Health Centers where abortions can legally be performed, for instance, is supposed to have at least one doctor. But the Rural Health Statistics Report (2019-2020) says that only 30 percent of these centers have a doctor, making for a shortfall of 3,611 doctors.

Few drugs in pharmacies?

There are also only a few pharmacists willing to stock medical-abortion drugs, especially in rural India. A recent study conducted by the Foundation for Reproductive Health Services (FRHS) India even says that there was an “abysmal stocking” of abortion drugs in 10 Indian states in 2018 and 2020.

Ipas Development Foundation head Vinoj Manning says that drug shortages are most often found in areas where there have been crackdowns on sex-selective abortions. The grey area between the MTP Act and the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act, 2003 — legislation enacted to curb instances of sex-selective abortions in India — has made stocking abortion drugs a bit of a liability for pharmacists who cited “heavy documentation, legal hassles, misconceptions on (medical abortion) drugs and harassment” as major deterrents.

This has led to a grey market for abortion drugs, the FRHS has found. Between January and March 2020, its researchers sent mystery shoppers without a doctor’s prescription to 50 pharmacists who had officially denied stocking abortion drugs in Madhya Pradesh. The survey found that 56 percent of pharmacists were in fact stocking abortion drugs off the books, indicating that the market could have been “driven underground.” According to women’s health advocate and former FRHS chief VS Chandrashekar who co-authored the study, some pharmacists sold medicine strips without their boxes to avoid detection.

In the meantime, the MTP Act has seen diverse interpretations in courts. Just this July, the Delhi High Court refused to allow a plaintiff to abort a 23-week fetus, saying “we will not permit you to kill the child.” The woman had been in a consensual live-in relationship at the time of conception and had sought to terminate her pregnancy after the relationship ended. Per the 2021 amendment to the MTP Act, abortions up to 24 weeks of pregnancy are allowed in case of “change of marital status during ongoing pregnancy (widowhood and divorce),” but not for unmarried women.

Days later, the Supreme Court allowed the termination, on the condition that an apex medical board assessed that it would not endanger the woman’s life. In the same week, the same court allowed a 17-year-old sexual assault survivor to terminate her pregnancy of over 26 weeks, reasoning that her misery would stand compounded if she were forced to bear the “mantle of motherhood at such a tender age.”

Abortion as a right

Such a variety of interpretations of the MTP Act illustrates the pitfalls of a law that sees abortion only as a medico-legal necessity — to save the pregnant woman’s life — and not as her right.

Chandrashekar also points out that while abortion in India is legal, Section 312 of the country’s Penal Code criminalizes “voluntarily causing miscarriage” even with the woman’s consent, except when the miscarriage is caused to save her life. This means the woman or anyone else involved in her pregnancy’s termination, including the pharmacist who supplied her medical-abortion drugs or the medical practitioner who undertook the abortion, could potentially be prosecuted.

A step forward may be to delink medical abortion using mifepristone and misoprostol from surgical abortion, as one is a simple course of medicine while the other is a surgical procedure. Medical abortion using drugs does not require even medical supervision. In Europe, organizations like Women on Waves offer teleconsults with doctors and mail the drugs as needed.

Pratigya Campaign, a consortium of SRHR organizations in India (including FRHS, Ipas, and others), recommends expanding the definition of legal abortion and especially medical-abortion providers, investing in comprehensive awareness campaigns about types of abortions and their legal status, and allowing medical-abortion drugs to be sold over the counter, citing the World Health Organization’s classification of mifepristone and misoprostol in its core list of Essential Medicines List 2019.

Chandrashekhar says, “It is important to drive home the point that gender identification can only be done in the second trimester, while medical abortions are most safely performed in the first trimester. The fear that free availability of abortion drugs could result in an increase in sex-selective abortions is exaggerated.”

Most of all, for the MTP Act to truly empower Indian women, it needs to view abortion as a right, not a medico-legal procedure performed under extreme circumstances. Till then, unintended pregnancies and high abortion rates will continue to mar the demographics of a country that prides itself on having one of the world’s oldest and most progressive abortion legislations.◉