|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

E

ach day blends seamlessly into the next where they are staying, so it’s not surprising that Raga Kogoya seems to have lost track of just how old her boys are now. They haven’t even been celebrating birthdays, but one thing Raga is sure of is that her sons should be in school. More specifically, her older boy King should be in junior high by now. On the other hand, the younger boy Berlian should be in sixth grade.

However, since they and several other families had to flee their homes in Nitkuri, a village in Nduga Regency, Papua Province, in December 2018, getting the boys and the rest of the refugee children to school has been a serious challenge. Then again, armed conflict always disrupts lives and has the potential of even destroying futures.

The decades-old armed rebellion in the Indonesian provinces of West Papua and Papua has been described as “low-key.” But for the residents of these provinces, which were formally annexed by Indonesia in 1969, there is nothing “low-key” about a conflict that has had them in constant anxiety, drives them out of their homes for long stretches of time, and tends to keep basic services — such as education — nearly out of their reach.

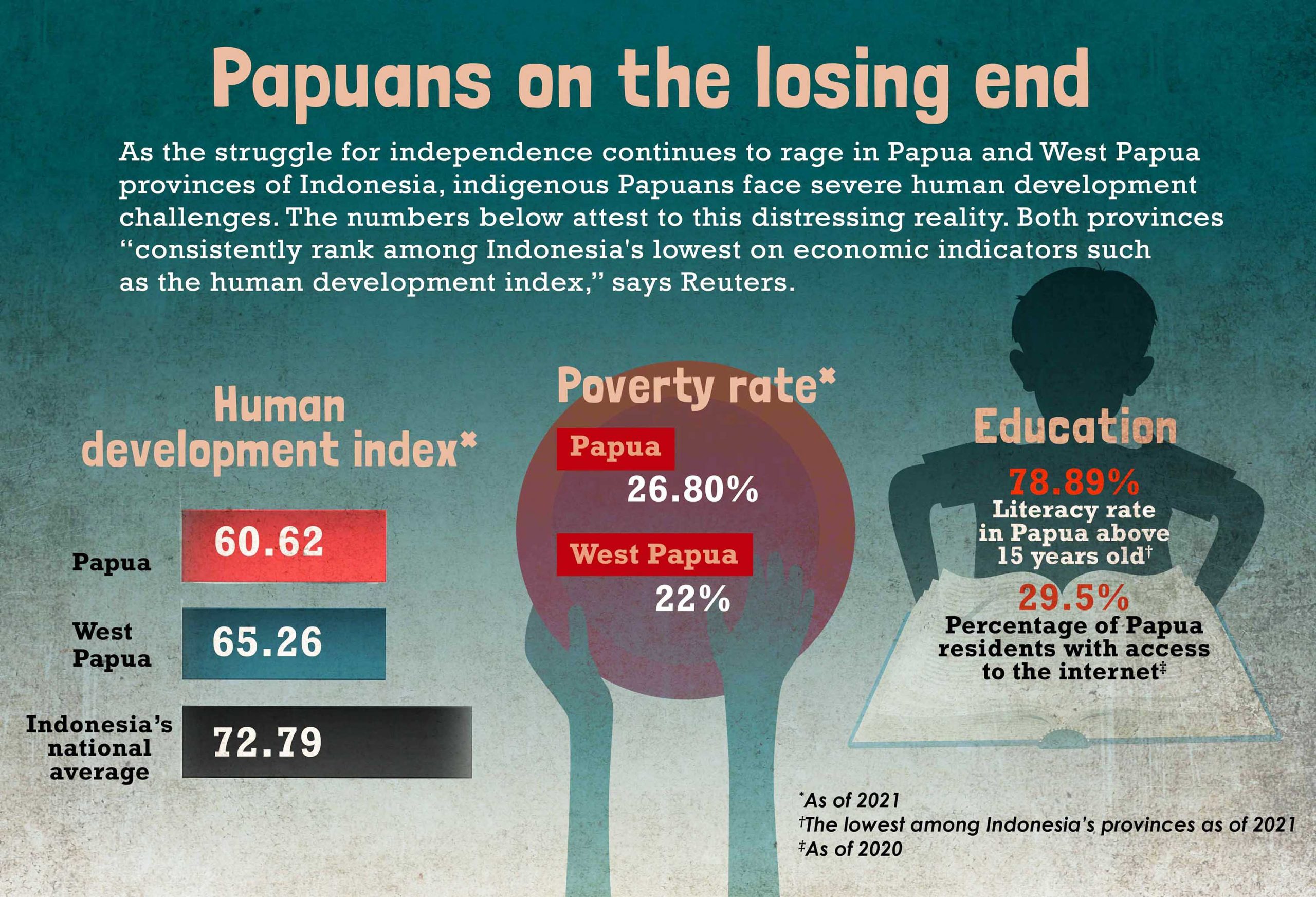

Not surprisingly, Papua had the lowest literacy rate of those above 15 years old among Indonesia’s 34 provinces in 2021, according to the data website Statista: 78.89 percent. That is at least eight percentage points below West Nusa Tenggara, which had a comparative figure of 87.39 percent, earning it the second to the lowest post.

And yet West Papua, which is just next door, had a literacy rate of 97.91 percent. According to Agus Samule, a lecturer from the University of Papua, Manokwari, one reason for the neighboring provinces’ contrasting numbers is the fact that conflicts in West Papua are more contained and occur less. Papua, he says, has more areas that have been turned into battlegrounds by the separatists (who refer to the entire area covered by West Papua and Papua as “West Papua”) and the Indonesian armed forces or TNI.

Nduga, for instance, has been declared a battlefield by the West Papua National Liberation Army (more known by its Indonesian acronym, TPNPB). This means it can no longer guarantee the safety of civilians, who have been advised to stay away from Nduga. As a result, families like the Kogoyas have been stuck in refugee camps, unable to go back to their homes.

Waking up to a nightmare

The camp where the Kogoyas and other Nitkuri residents live is in Sekom village, about two hours by car from Wamena, the nearest urban area. There are currently 65 families in the camp or a total of more than 540 people. The camp can only be reached by foot, on roads that are all rocks and mud. From the point where a vehicle can no longer be used, the walk to the camp takes about an hour.

Still, children who are determined to learn can arguably go to the nearest school that would require them to walk for several hours each way — but only if they or their parents remembered to take with them their population identity file while they were trying to escape the fighting between the separatists and TNI. Online education is also nearly impossible in Papua, which ranks last in households’ internet accessibility among Indonesian provinces, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). While 89.05 percent of people in the national capital Jakarta have access to the internet, Papua’s comparable figure is just 29.5 percent, says UNICEF. The independent information provider ACAPS has also noted that since 2019, the national government has implemented an internet slowdown in Papua.

The province has been in a state of emergency since December 2018, when 19 men who had been working on the Trans-Papua Highway in Nduga were ambushed and killed. The TPNPB were suspected of carrying out the massacre, and a joint military and police operation was launched to flush out the rebels thought to be hiding among the residents of Nduga villages.

But the manner in which the operation was done proved to be repressive, if not ruthless, forcing people to flee in fear. ACAPS says that since 2018, the armed conflict in Papua has resulted in an estimated 60,000 to 100,000 internally displaced people.

Kobolge, who is now 17, remembers how he was awakened by loud noises one morning nearly four years ago. He says that at first, he thought he was having a nightmare. Stepping out of the house, he saw smoke and houses on fire and heard screams interspersed with explosions and the sound of helicopter propellers. According to Kobolge, who declines to share his surname for this story, he and his family soon ran away, along with several of their neighbors.

“Then,” he recounts, “we entered the forest and walked for miles in the wilderness in search of a safe place. After a long journey, we finally got here, in Sekom village.”

Kobolge still considers himself lucky. Like many children, he was also forced to stop school for two years, but he is now back in the classroom as a junior high school student. While his parents stayed behind in the refugee camp, Kobolge goes to a private school in Wamena, sponsored by a local church. Relatives living in Wamena take care of his board and lodging.

Since the joint military-police operation began in Nduga, there have been about 4,000 children from the regency who have dropped out of school. Academic Agus, for his part, says nearly half a million Papuan children are currently out of school.

“Shaming” the state?

“I want to be able to go to school like Brother Kobolge,” says King Kogoya, who dreams of becoming a teacher someday.

His mother Raga wants that to happen, too. For now, though, she says, “I have no choice but to try to provide the knowledge I have to the children here. There is no school, so they only study informally. Education is our only hope to change Papua’s future, change our fate for the better.”

Raga, an economics graduate, had set up an “emergency school” for the camp’s children early on with the help of the other refugee parents. Although the children had only used books and a few textbooks that they shared with one another, the school thrived and gave hope to the refugee families. But it lasted only three semesters and was forced to close down in mid-2020.

“TNI came to me and said that the refugee school only brings shame to the state,” Raga recalls. “And yet they didn’t offer an alternative (course for schooling the children).”

Papuan intellectual Theo Hesegem says, “I once proposed the following idea: what if the Nduga government communicated with the Wamena government so that refugee children could attend school in Wamena, a city close to refugees? But until now, further discussion (on this) has yet to happen.”

Raga says that when the other parents were setting up the school, she had a simple goal: for the children to have a different fate from their parents who, in their childhood, must have dropped out of school because of the Mapenduma military operation led by Lt. Gen. Prabowo Subianto in 1996. The conflict was then in one of its more serious stages in Nduga.

Raga was a junior high school student in Wamena at the time. She recalls that her schoolmates chose to leave Wamena and headed home to Nduga to help their parents.

“The refugees now are the children of my friends who were also affected by the Mapenduma operation in 1996,” Raga says. “I don’t want them to have the same fate as their parents. That’s all I hope for.”

But she says that she and the other parents shut down the school, as TNI wished, to spare the children from any more trauma and to avoid aggravating what was already a difficult situation for all of them.

“Children have traumatic experiences with TNI,” says Raga. “When they saw the troops entering our schoolyard, the kids immediately jumped over the fence. Refugee children are afraid of them.”

A “humanist” approach

Made Supriatma, a military expert from the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, explains that the Indonesian military probably ordered the emergency school to shut down to cut communication between the umbrella organization Free Papua Movement (OPM) and the outside world.

“If we look at the way the military thinks,” he says, “this emergency school has the potential to open up lines of communication between the OPM and outsiders, who usually hide behind the pretext of ‘humanitarian work.’ But the military failed to see this more broadly. They failed to find a bridge between security and humanity.”

Commenting on TNI Commander General Andika Perkasa’s “humanist approach” that would supposedly solve the problem in Papua, Made says, “They chose to send soldiers to be teachers instead. Meanwhile, Papuan society’s trust in the Indonesian military is very low. The children in Papua know that it was the soldiers who opened fire on their families in their village. How could the soldiers be sent as teachers? Who would want them?”

For Made, the heart-and-mind operations to win over Papuans could be a success only after the physical fighting has abated. Or, he says, once the Indonesian military has successfully occupied one region.

“After the conflict is over, the military may restore the education sector using their method, and along with that, public facilities and access to Papua that may be built better,” Made says. “That will succeed in gaining the sympathy of the Papuan people. But that hasn’t happened yet, right? I guess this is just a political gimmick. The conflict will not be resolved if patterns toward peace negotiations are not improved. The approach must be (through dialogue).”

Yet, he says, instead of negotiating, the Indonesian military continues to increase its forces in the region each year. According to Made’s research, the number of soldiers dispatched to Papua has nearly doubled under General Andika’s command.

“If usually around 9,000 personnel are deployed for security in Papua in one year, in 2021, the number rose significantly,” Made says. “About 15,000 soldiers were sent to Papua. The increase in the number of personnel is also proportional to the increasing clashes and tension between the TNI and TPNPB.”

“If they keep washing blood with blood,” Raga remarks, “we will never see the end of this long war. The war is not only taking lives, but also ideals, and the future of Papuan children.” ●

Reno Surya is a freelance writer based in Surabaya, Indonesia. His work has also been featured in various outlets, including VICE Indonesia, The Jakarta Post, Aljazeera English, Project Multatuli, and New Naratif.