|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Editor’s note: For many governments, the lockdowns they enforced amid the COVID-19 pandemic also gave them an opportunity to intensify the suppression of basic freedoms. Under the guise of public health and safety, many restrictions were put in place that limited the movements of many non-profit and civil society organizations across the globe.

Today, nearly three years later, governments have set their sights on cutting off the lifeline for these groups by enacting laws that scrutinize their funding sources, among others. Thailand’s Draft Act on the Operation of Not-for-Profit Organizations is one such law. One glaring cause for concern: Under the draft law, the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security heads the Committee on the Promotion and Development of Not-for-Profit Organizations which is tasked to procure funding and decide to which groups these funds will go.

And, while the Thai government has conducted a public consultation and amended parts of the bill, critics say these efforts are not enough.

E

ver since the cabinet resolution to approve the Non-profit Organization Act on Feb. 24, 2021 was passed, objections immediately surfaced from the civil society sector, including both international and domestic organizations.

The first draft had many problems, including compulsory registration with stipulated penalties, limits on the areas of work of organizations with many prohibitions, for example, that organizations must have no impact on state security or good morals, as well as criminal penalties, and a greater bureaucratic burden on organizations.

Although some details in the current bill, for which the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security held a public hearing in April 2022, have been amended, the main points in the original draft remain. These include areas of permitted work under Section 20, which attracted the greatest criticism from the start, as well as the section which stipulates penalties. While the criminal offenses have been removed, the range of responsible persons has increased to include those working in the organization.

In addition, this bill allows the Committee to interpret which organizations fall under this law even if they do not have to register.

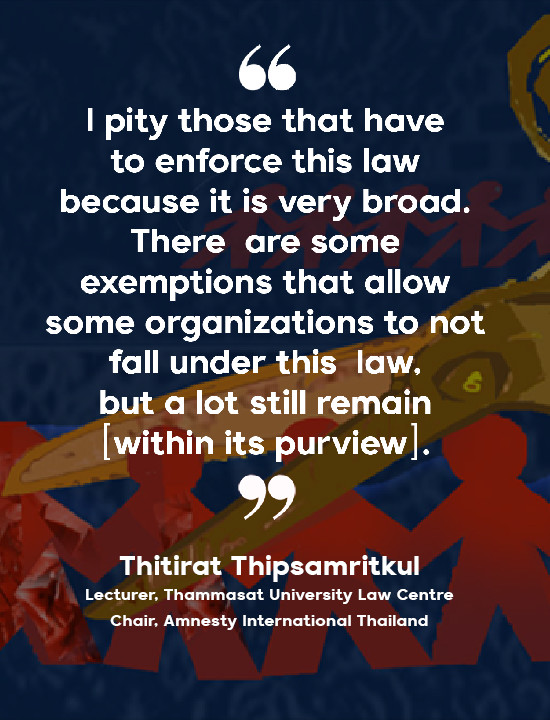

Following is an excerpt of an interview with Thitirat Thipsamritkul, a lecturer at the Thammasat University Law Centre, and also the chair of Amnesty International Thailand. She shares her views on the impacts that this bill may have if passed.

Thailand is often questioned on the international stage about its progress in resolving its human rights problems. If this law is enacted, what effect will it have on the human rights issues in Thailand?

It will definitely have an effect … There is the issue of protecting human rights defenders, [who stand to] … get threatened or have their rights violated [if the law is passed]. In this context, Thailand is often questioned on topics such as enforced disappearances, torture, the right to bail, fair access to the justice system, as well as on the use of … legal processes — called Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation — to obstruct or harass the work of human rights defenders, including the media and NGOs. This harassment may be by a state or non-state entity.

This is very worrisome because the violation happens slowly without us noticing, or when we do notice it, it is already too late to fix it because the networks in the movement have already become too weak.

The issues of human rights and international trade seem to have become inseparable. The case of labor in the fishery industry is clear, as well as business and human rights, which has become a trend for many years. How will this kind of law limiting the work of NGOs impact the economy?

The direct effect [of the proposed law] is on NGOs that try to question or suggest raising standards to protect the rights and freedoms affected by business operations. We should not assume that all businesses must violate rights. But in some industries, there are more likely to be clear or violent violations.

If the work of these organizations is restricted, it will impact the credibility of businesses in Thailand …. Bangkok is seen as a convenient place as a city with a relatively reliable infrastructure, and some businesses or activities that may impact human rights … are monitored by international non-governmental organizations which are normally set up in Thailand.

But when the rights situation in a country has deteriorated or there is less protection, activities between countries are more obstructed.

This becomes a signal for the business sector or investors as well that, although today the restrictions on rights may still be within the circle of activists as interference in NGOs or rights and freedom, they may question if the interpretation of the law is arbitrary or illegal, will it then extend into their business space?

When you talked about using law inconsistently or unlawfully, how does this bill allow such a law to come about?

Section 20, for example, which people speak of a lot, is quite broad. We have always said that laws cannot be written in that much detail, but if they are written broadly, there needs to be a principle to interpret them.

Another issue is the officials’ discretion in providing support to some organizations. It may open a way for officials to discriminate and act differently between good children’s organizations that praise the government and organizations which criticize what the government does. This is in Section 18.

In addition, there is the issue of declaration of funding sources. It says that if the details are complete, then there is no need for further explanations. This raises the question, what do they call complete? There are loopholes for officials to use their discretion widely.

Although support such as financial funding is also mentioned in the draft law, how much good can this fund do under this Act?

There has always been a mechanism to support the work of NGOs. There are Thai funds in the state sector that NGOs could utilize. However, the question one should ask is: Can the fund be accessed without discrimination? Can everyone equally access it? This might be the bigger issue.

The second issue is to motivate people to donate. Just compare how easy it is to get a tax refund from donating to a temple and to a civil society organization.

Yet, when civil society organizations ask for tax deductions, they are faced with unreasonable conditions. There need to be some conditions, but they should make it easier than this. Monitoring should be transparent and fair. These conditions will distinguish which kind of organizations should be particularly checked for money laundering or which are truly working for the public interest. What the state should do is change the mechanisms so that NGOs could easily gain more funding.

How necessary is this Act since many organizations have noted that there is already an existing law overseeing Not-for-Profit Organizations and already a mechanism in place to inspect finances?

I think that the Act is not necessary … If you ask if assemblies or associations of the people should be limited or not, I think it should be limited only at the level where it will create a risk. Like an assembly to found a company or an assembly to hold some sort of activity. We need to start from the basis that humans have the freedom to do whatever they want as long as it does not create risks or make trouble for others, but if it does, then the law should take over.

Right now, the state has yet to prove that assemblies or associations of the people, no matter if it’s a Not-for-Profit Organization, foundation, or anything else, create any kind of risk to the country. There is no explanation. I don’t think it can move forward. Why does there need to be a law for this?

On the other hand, lawmakers seem to not have thought about what those implementing it will do.

I pity those that have to enforce this law because it is very broad. There are some exemptions that allow some organizations to not fall under this law, but a lot still remain [within its purview].

I understand that they tried to write the law in a way that facilitates operations to a point because they have always been attacked, since organizations already have to report to the Revenue Department and report to the Department of Provincial Administration annually. And now they have to report to the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security as well?

The Council of State tried to amend the bill so that if an organization has already made its reports, the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security can pull out information from these ministries directly. The question is, is there a system in place that allows this information sharing to really happen?

Nowadays, internal coordination among agencies in the Thai government system is a great problem, otherwise we wouldn’t have needed to establish the Digital Government Development Agency to help with this.

We cannot begin to imagine how many officials are required to operate this. The next question is, if it can be done, what is it for? What benefits come from using our taxes for this [draft law]? What really is the objective of this law? The state needs to be able to answer [these questions]. ●

This article was first published by Prachatai on June 23, 2022. This excerpt is being republished here by the Asia Democracy Chronicles with permission. To read the full interview, please follow this link.