|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

S

ahil Ganjoo’s family used to call India-administered Kashmir home. So when he returned to the valley in 2019 to take up a government job, it didn’t take Ganjoo long to get used to life there. He made new friends, signed up at a local gym, and enjoyed visiting Kashmir’s many picnic spots.

However, in early June 2022, Ganjoo packed his bags, left his rented apartment, and rode his motorbike for six hours to get to Jammu, where his parents now live. Ganjoo wants to leave Kashmir temporarily, if not for good, a decision he indicates hasn’t been easy to make.

“I was respected by everyone,” he says. “My colleagues always showed affection toward me.” But, he adds, “I never thought the situation would get worse like this.”

That “situation” refers to a spate of killings of civilians in the last 10 months in Kashmir, which is claimed by both India and Pakistan, but with each controlling only parts of it.

India-administered Kashmir has been a battlefield between militants and Indian armed forces and police for decades. Lately, however, civilians have become targets for assassination by suspected militants. Official data show that so far this year, such targeted killings have already left at least 19 people dead.

Just three weeks before Ganjoo headed for Jammu, for instance, Rahul Bhat was shot at his government revenue department office in Budgam district in central Kashmir; he was pronounced dead on arrival at a nearby hospital. Then on the last day of May, schoolteacher Rajni Bala was shot dead in South Kashmir’s Kulgam district. Two days later, Vijay Kumar suffered the same fate at Ellaquai Dehati Bank, also at Kulgam, where he was a manager. A few hours later, two migrant laborers working at a local brick kiln were shot at in Budgam. One of them survived the attack; the other, 17-year-old Dilkush Kumar from Bihar state, did not.

All of these attacks have been attributed to so-called “hybrid militants” who, unlike full-time militants, do not go underground but resume their usual daily activities after an assignment. Like the civilian targets, hybrid militants are the latest additions to the ever-evolving Kashmir conflict that India’s current leaders seem determined to downplay. Indeed, an explainer published recently by the International Crisis Group asserts that the militants are targeting civilians partly to disprove the central government’s claims that Kashmir is back to normal and that it is already “business as usual” there.

The main triggers for the targeted killings, however, appear to be the policies on Kashmir imposed by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, some of which are stoking fears among Kashmiris of forced demographic change in the region. Kashmir is the only Muslim-dominated region in India, which is a secular state despite Hindus making up the majority of its 1.4 billion people. Many of the civilians being killed in the region are either Hindus or migrants or both, although the targets have also included Muslims perceived to be aiding or supporting the directives of the central government.

“There is fear of demographic change among the public in Kashmir, and the spike in targeted killings by militants is an outcome of that,” says a Kashmir-based scholar, echoing other observers. “When there was a lull in militant activities post abrogation of semi-autonomy, BJP thought they were successful in controlling militancy. But it has returned in its worst form.”

In early June, a letter that was purportedly written by Kashmir Tigers — one of the newly emerged militant groups that have claimed responsibility for recent targeted killings — said that non-locals should not settle in Kashmir. In an apparent reference to the recent killings, the letter, the authenticity of which could not be verified, warned, “Anyone involved in the demographic change of Kashmir will meet the same fate.” (According to the police, the Kashmir Tigers group is an offshoot of the Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba, an insurgent group that claims to be fighting the Indian state over control of Kashmir.)

From state to territory

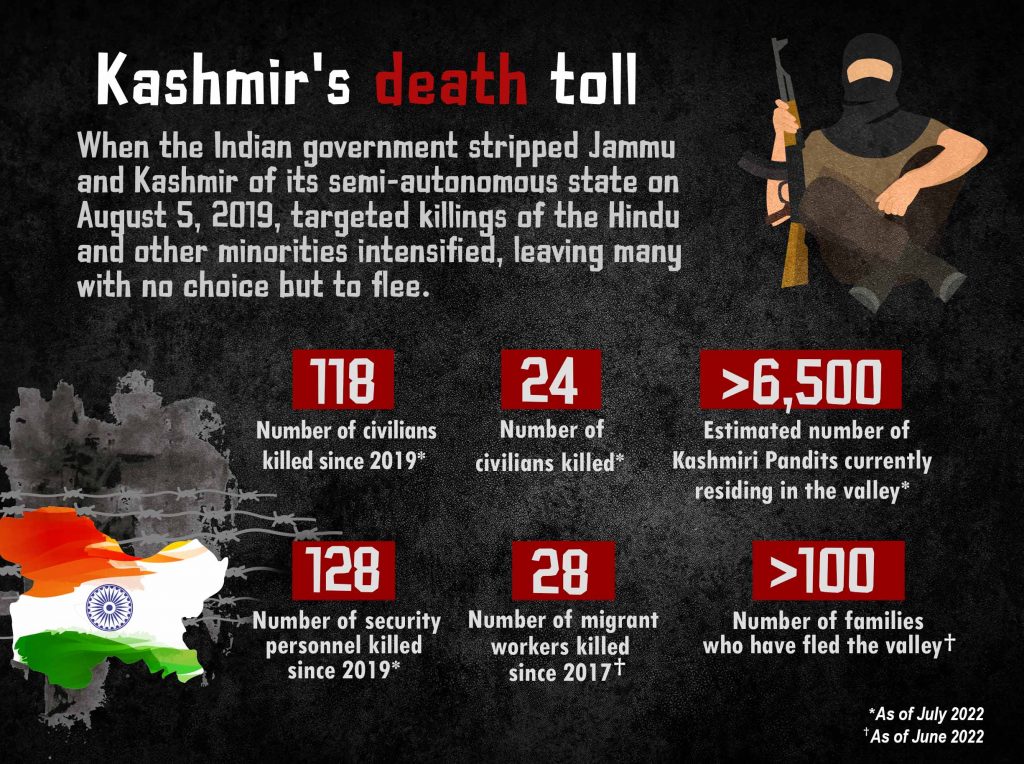

In August 2019, the BJP-led central government stripped Jammu and Kashmir State of its semi-autonomous status and downgraded it to being a union territory, which placed it under New Delhi’s control. The central government also revoked Article 35A, a legislative law that prohibited outsiders from buying land and taking up state jobs in Kashmir.

Following these legislative changes, BJP passed a new set of land and domicile laws that opened the gates for outsiders to buy land and settle in Kashmir. These laws triggered fears that BJP would settle outsiders in Kashmir to change the region’s demographics. According to the new rule, domiciles will include those who have lived in Kashmir for a certain period of time. Official data indicate that since the new law came into existence and up until August 2021, over 4.1 million domicile certificates were distributed in Jammu and Kashmir.

Justifying the dilution of J & K’s semi-autonomous status, BJP has consistently claimed the move would usher in a “new era of dawn” in Kashmir and reduce conflict in the region. However, more than two years later, the realities on the ground depict a different story.

For one, there has been a spike in militant activities. The first half of this year has witnessed a steep rise in militancy in Kashmir as compared to preceding years. In less than six months, police themselves say, more than 100 militants including 72 locals and 30 foreigners were killed in different encounters. That is twice the number of militants killed last year in the same period.

The recent spate of killings of civilians has also reignited fears among a particular Hindu community in Kashmir: the Pandits, who trace their roots to the valley. Although non-Pandit Hindus have also been among the victims — such as schoolteacher Bala from Jammu and banker Kumar from Rajasthan — the violence has had the Pandits reliving nightmares from decades ago, when many of them fled the valley.

In the wake of an armed rebellion in the part of Kashmir controlled by India in the late 1980s, many Kashmiris, including Pandits, lost their lives. Being in the minority, tens of thousands of Pandits apparently decided it was safer if they uprooted themselves and went to Jammu, which is Hindu-dominated, as well as to other Indian states. Government data suggest that around 154,080 Pandits migrated from Kashmir in the 1990s, although many Pandit groups say the number was much higher.

In 2008, the central government under then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh of the Indian National Congress launched a special program aimed at bringing back the Kashmiri Pandits to the valley. Promising 3,000 government jobs to the returnees, the government also built camps to house them.

After the BJP won control of the central government in 2014, the Modi administration opened up 3,000 more government jobs in Kashmir for Pandits. The recent changes in the land and domicile laws have been seen as benefiting the returning Pandits as well.

Observers say that these may help explain why Pandits have been among those targeted by suspected militants. A Kashmiri Pandit who declines to be named comments, however, “Somehow, we can say the targeted killings are an outcome of the recent decisions taken by the government. But Pandits aren’t responsible for that. We are natives of Kashmir. Our ancestors have lived here.”

Estimates are that more than 5,000 Pandits returned to Kashmir in the last 12 years, among them Sahil Ganjoo and the recently deceased Rahul Bhat. Most of them lived in seven temporary transit camps located across Kashmir, although the government also forced many Pandits to rent apartments.

In need of safety and security

Pandits still in Kashmir say that almost everyone who had been living in rented accommodations has left the valley while more than half of the families residing in the transit camps have gone to Jammu. Ganjoo, who got his job at the Power Development Department through the special prime minister package program, says that his parents repeatedly called him up, pleading for him to leave when the killings became more and more frequent. When he finally heeded them, he did so with several of his fellow Pandits.

“Everyone’s priority is safety and security,” says Ganjoo. “How can anyone live in a place where there is a threat to his life?”

After reaching Jammu, however, Ganjoo was informed that he had been transferred to an office close to his rented flat in Kashmir. “My new office is indeed a bit closer to my rented apartment than the earlier one,” he says, “but that doesn’t mean I am completely safe now. Also, I will not confine myself to my accommodation. I will have to go to the market to buy essentials.”

On May 27, 2022, a group of Pandits met with J&K Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha and demanded that they all be temporarily relocated to Jammu. According to some of the Pandits, Police Inspector General Vijay Kumar told them that it would take three years to rid Kashmir of militants.

“Police have accepted Kashmir will not be terror-free for the next three years,” says Ranjan Jyotshi, who was at the meeting with other Pandits. “So, it is clear we can’t stay here to wait our turn to get killed.”

“We were doing our work with honesty and dedication and will continue to do so,” says Jyotshi, who has been with the social welfare department in Kashmir since 2010. “But we need a threat-free atmosphere first.”

The Press Trust of India (PTI) has since reported that the Kashmir administration will relocate Pandits to safer places — but not outside Kashmir. A senior government official also told the English daily The Hindu that the central government doesn’t favor relocating Pandits as that would be a repeat of the 1990s, when thousands of Hindus migrated from the valley.

Sinha meanwhile has assured the families of the recent victims of the government’s full support. The administration has provided a government job to Bhat’s wife and financial assistance to the family and has pledged to pay for the education of the couple’s daughter. ●

Aamir Ali Bhat is a Kashmir-based independent journalist. He writes mostly on human rights abuses, politics, the environment, and gender. His work has appeared in The New Arab, The Wire, Dawn Herald, The Globe Post, Asia Democracy Chronicles, The Quint, Outlook, Firstpost, and elsewhere.