|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

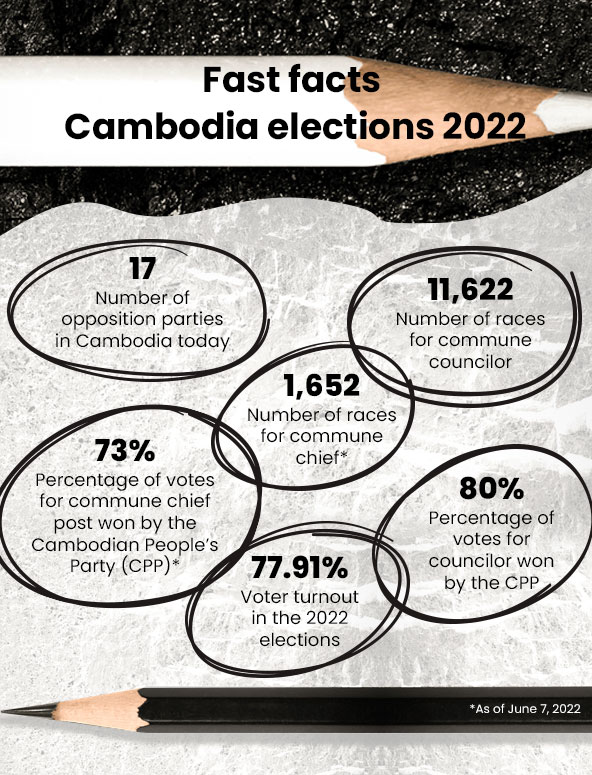

If Cambodia’s recently concluded commune council elections were supposed to foreshadow what will happen at the country’s national polls scheduled next year, then opposition parties and their supporters can expect more trouble ahead. This is even as some observers think the main opposition, Candlelight Party (CP), had a good showing at the elections, despite its winning only 21.78 percent of the popular vote while the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) took 72.7 percent.

On June 5, 2022, Cambodia’s 1,652 communes held elections for commune chiefs and councilors. Voter turnout was around 78 percent which, according to opposition groups, was far less than those in previous elections.

Some 17 opposition parties, including CP — currently the second-largest political party in Cambodia — ran in the polls against the CPP in the commune elections. Although CP managed to capture just less than a quarter of the popular vote, some observers say that that was already a feat considering the “creative storytelling” by authorities and the ruling party that was used to hale CP supporters and activists to court before the elections.

Other observers say, though, that the Hun Sen government merely “allowed” CP to win a token number of the posts to avoid having Cambodia being called a one-party state. In truth, the CPP-dominated National Election Committee had even barred some 150 CP candidates from running in the commune polls.

The Candlelight Party is the second-largest opposition group, making it the main opposition party in Cambodia today.

Keo Bun Hok, a resident of Phnom Penh’s Boeng Keng Kang III commune, also says that in the run-up to the June 5 elections, people perceived to be in support of CP were being accused left and right of all sorts of crimes and illegal activities, and taken to court.

“It is a known fact that authorities have threatened a number of people who do not support CPP,” Keo Bun Hok says. “I believe that the people still supported [the] CNRP but they will not show their support openly.”

Ghost from the past

CNRP refers to the Cambodia National Rescue Party, which was a merger of the Sam Rainsy Party and the Human Rights Party, both opposition groups. Formed in 2012, it captured nearly 45 percent of the votes in the 2013 parliamentary elections and around 44 percent in the 2017 commune elections.

However, the Cambodian Supreme Court forcibly dissolved it five months after the 2017 polls. CNRP leaders and officials have since been either arrested or forced into exile abroad. The case was based on a complaint filed by the Ministry of Interior, which accused CNRP of attempting to overthrow the government with the help of the United States.

Just a week or so after the latest elections, a Phnom Penh court sentenced dozens of supposed CNRP supporters, including Cambodian-American lawyer Theary Seng, to jail, with terms ranging from five to eight years.

Just a week or so after the latest elections, a Phnom Penh court sentenced dozens of supposed CNRP supporters, including Cambodian-American lawyer Theary Seng, to jail, with terms ranging from five to eight years.

Although observers say CP’s showing in the recent elections was far less impressive than what CNRP was able to achieve years ago, they say that there is still a chance that it can go the way of CNRP.

CP is the former name of the Sam Rainsy Party, although exiled opposition leader Sam Rainsy has been careful to distance himself from it. Neither the Human Rights Party nor the Sam Rainsy Party was dissolved as a result of the formation of the CNRP.

This early, a CP commune leader-elect has been arrested for a robbery he allegedly committed two decades ago. Nhim Sarom, the elected Chamna Loeu commune chief in Kampong Thong province, was picked up by police at his house on June 22, 2022; he was released on bail the day after.

One of CP’s vice presidents, Son Chhay, is also facing a lawsuit filed by CPP for his alleged “distortion of facts” during an interview about the June 5 elections. CPP is demanding the equivalent of US$1 million as compensation.

The online Cambodia Daily, which ran the interview, had quoted Son Chhay as saying that people had been “intimidated” and that votes were “bought and stolen.”

The National Election Committee has warned Son Chhay that it may also “take legal action for any baseless allegations.”

However, Sam Kuntheamy, executive director of the Neutral and Impartial Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia, says that threats before and during elections often occur. Some parties have filed complaints with the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Justice, he adds, but it seems that there has been no intervention from officials.

“The authorities often harassed citizens by taking them to court and the police for questioning without proper reason,” he says. “Most people without legal knowledge are afraid and do not participate in political activities anymore.”

In fact, in the run-up to the recent elections, at least a hundred supporters of the opposition were arrested for alleged incitement and conspiracy to commit treason. In addition, some 95 CP supporters were summoned to court for questioning over similar allegations, while about 40 other CP supporters found themselves being called by the police for questioning for unclear reasons.

Some CP supporters meanwhile say that they were arrested and detained for reasons that they say were false. Ansar Chambok resident Ouk Sau Varin, for instance, says that he was accused of falsifying land documents, but believes authorities just wanted to harass him for being a CP supporter. He says that authorities were warning CP supporters that they “will be deprived of their ID cards and will not be provided administrative services, and have their land confiscated.”

CP candidates harassed

Not surprisingly, CP candidates went through similar experiences as well. CP candidate Oeur Chea of Kansom Ok commune, Kampong Trabek district, Prey Veng province, for example, received an order to appear in court to clarify allegations of forgery.

Fifteen CP candidates in Kang Meas district, Kampong Cham Province, were also asked to appear before the Kampong Cham Provincial Election Committee over allegations that they distributed money among voters during the campaign.

Cambodians trooped to the polling stations on June 5, 2022. Voter turnout, however, was lower than in previous elections.

“On May 23, I helped representatives at Sdao commune and in 11 communes in Kang Meas district,” says Kong Raiya, a Kang Meas district leader from CP. “I donated US$100 per commune to spend on the election campaign. The activists need to pay for gasoline, food, and buying campaign materials. It is not illegal.”

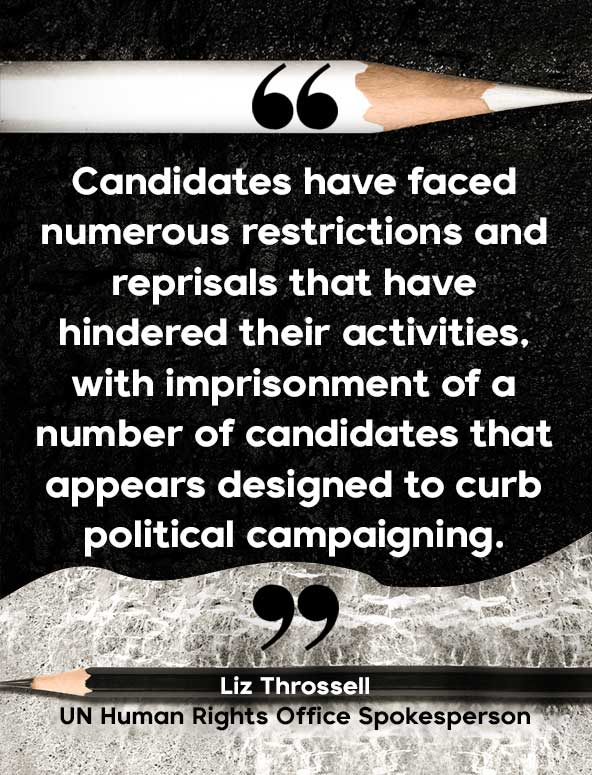

Four days before the polls, UN Human Rights Office Spokesperson Liz Throssell was moved to issue a statement to address what she described as a “paralyzing political environment” in Cambodia.

“Candidates have faced numerous restrictions and reprisals that have hindered their activities, with imprisonment of a number of candidates that appears designed to curb political campaigning,” Throssell said in the statement. “Four days before the election, at least six opposition candidates and activists are in detention awaiting trial while others summoned on politically motivated charges have gone into hiding.”

“The latest bout of political obstruction follows on from the systematic shrinking of democratic space documented by the UN Human Rights Office over recent years, which undermines fundamental freedoms and the right to participate in public affairs,” Throssell continued.

In a speech on Cambodia read by a colleague at the European Parliament in May, High Representative of the European Union Josep Borrell also said that the EU has “continued to raise our voice against the shrinking of the democratic space, including at the Human Rights Council, where the EU has also co-sponsored resolutions on this issue.”

Sources: Spotlight-Cambodia, Reuters

“The EU reiterates its call on the Cambodian authorities to take all measures to ensure democratic elections and initiate a process of national reconciliation through inclusive dialogue,” Borrell said. “We strongly believe that democratic inclusion and dialogue, including with civil society, is key to lasting peace and stability.”

Rebuttal from CPP, officials

CPP spokesman Sok Eysan says, however, that the allegations made by citizens and opposition party officials are not true.

“If they did not commit the crime, there would be no police and court summons for questioning,” he says. “They really made mistakes and were reported by the people to take legal action to prevent many other crimes.”

“We cannot assess the situation [on] only one side, but we must find the cause for all parties to get real information to avoid slandering the Cambodian government through some opposition officials,” he adds.

National Election Committee Spokesperson Hang Puthea insists as well that the committee has followed the law and that any accusations or perceptions from the EU regarding the Cambodian election are their individual opinions.

“Importantly, the National Election Committee has complied with Cambodian law, and we are not interested in any of the comments from outside,” he says.

Ministry of Justice Spokesperson Chin Malin, for his part, comments that the courts are independent bodies based on facts and the law and that the ministry, which belongs to the executive branch, has no jurisdiction and authority to interfere in court affairs. According to Chin Malin, the ministry has no authority to issue orders to the court, but only provided guidelines to expedite the case process based on the law to resolve case congestion and overcrowding in prisons.

“Participating in the court proceedings is the only legal way to defend oneself, relying on lawyers to assist in the court proceedings,” he says.

As Am Sam Ath, deputy director of the local human-rights organization Licadho, sees it, however, the issue of rights and freedoms of civil society organizations and opposition parties in Cambodia remains a challenge, with no significant changes in recent years.

Then as now, as he opines, opposition parties and civil society organizations working on human rights have faced restrictions on rights and freedoms. He says, “I would like to call on the government to reform the law on civil society organizations and address their concern.” ●

Hay Setha is a reporter from Cambodia.