|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

John Lee Ka-chiu, the cipher who is Hong Kong’s incoming chief executive, has tried to dispel notions that he has little experience in running a city by saying that his 35 years in the police force has enabled him to glean at least four key points in governance. As translated by the Hong Kong Free Press from a June 6, 2022 piece, Lee wrote for the state-owned newspaper Wen Wei Po, these points are the need to “rise to the challenge,” “value the results of execution,” “forge team spirit,” and “be vigilant in peace time.”

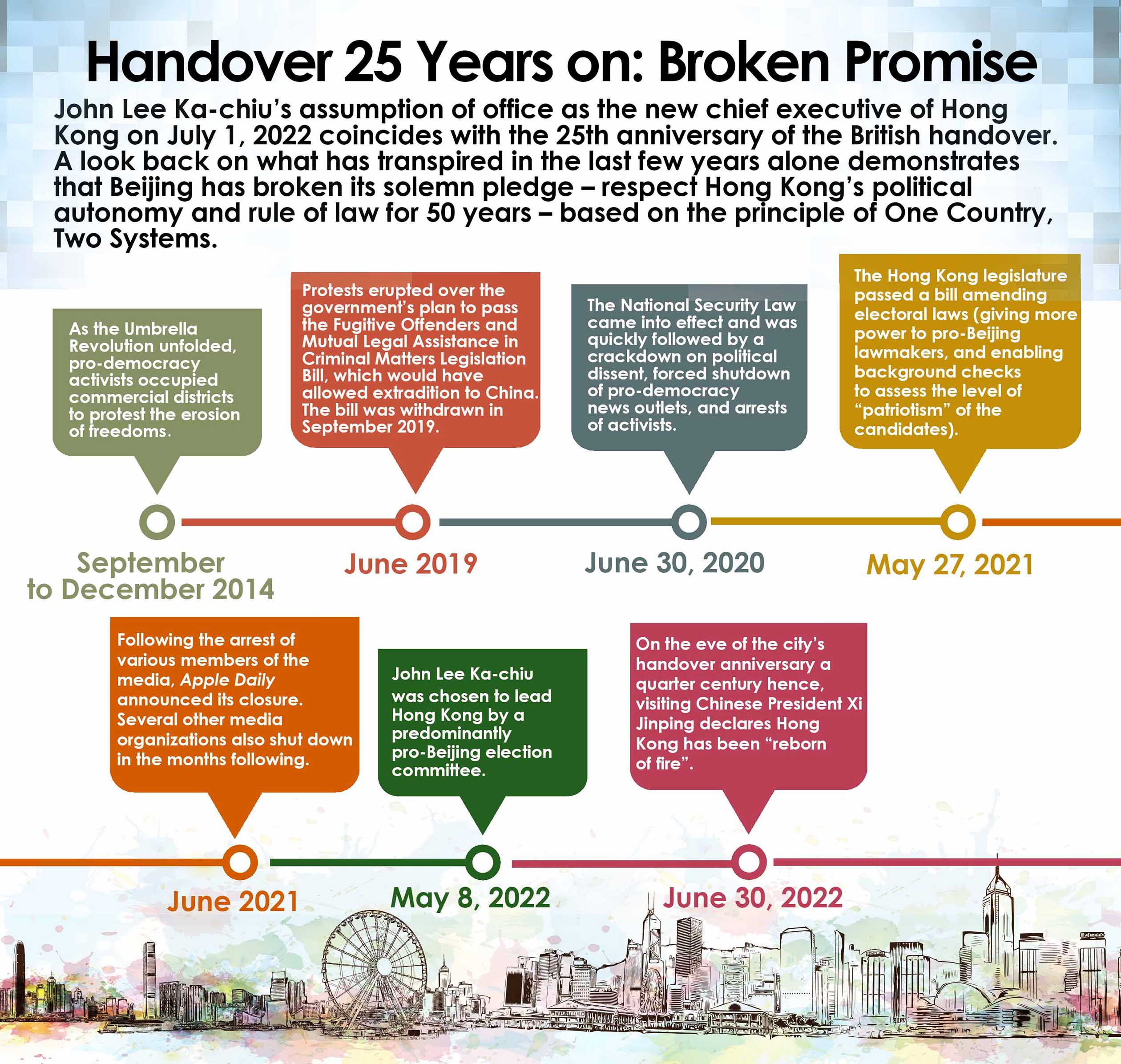

Lee, 64, is set to be inaugurated as Hong Kong Special Administrative Region’s sixth-term chief executive on July 1. He has already met with Chinese President Xi Jinping, who was quoted by state media as saying that “the administration of the new government will definitely bring forth a new atmosphere, and compose a new chapter in Hong Kong’s development.” The Chinese State Council has also appointed members of his Cabinet, which Lee described as “united and loyal … and results-oriented.”

Lee’s rise to power, however, has befuddled many of the city’s pundits, who have been hard-pressed in trying to explain why the former security official suddenly became Beijing’s apparent “favorite.” Meanwhile, Hong Kongers have been worried since his election and are bracing for even more curtailment of their freedoms.

On July 1, 2022, John Lee Ka-chiu will be inaugurated as Hong Kong’s chief executive. Many pundits, however, are hard-pressed to explain why Lee became Beijing’s apparent “favorite.”

Lee, after all, was the driving force behind the trigger for the unprecedented unrest in Hong Kong in 2019: the Extradition Law Amendment Bill, which was being pushed publicly by outgoing Chief Executive Carrie Lam, but which was actually Lee’s responsibility. As Hong Kong’s then security chief, he also oversaw the arrests of pro-democracy supporters and raids on activists’ homes and newsrooms in the city.

Not surprisingly, a spate of arrests of human rights activists in the months leading up to Lee’s election in May (where he was the sole candidate) also had many observers thinking that the crackdown could have had something to do with the man who was to become their new leader, and a foreshadowing of the kind of government he would head.

A series of arrests

For sure, these observers could only have been convinced they were right when on April 6, the day that Lee announced his candidacy, police arrested six people, including citizen journalist Siu Wan Lung and former Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions Chairman Tang Kin Wah for allegedly causing a nuisance and inciting hatred toward the administration of justice in Hong Kong during court hearings between December 2020 and January this year. One court insider says, though, that both men had just clapped their hands in court, and the judges then had not even found them in contempt of court for doing so.

Then on April 11, media professional and scholar Allan Au was arrested on suspicion of “conspiracy to publish and/or reproduce seditious publications.” Before his arrest, Au, who has written commentaries for many years and is considered a moderate, had commented on Lee’s election campaign. When asked how he could convince foreign investors of the arrests of media professionals, Lee — then fresh from his resignation as Hong Kong’s second in command — stressed that freedom of speech and press freedom are protected by the Basic Law.

Interestingly, it has been revealed that several international and local news organizations have been barred from covering Lee’s inauguration. According to one local news outlet, a government spokesperson cited the “latest epidemic situation, security requirements, and venue constraints” as reasons for limiting the number of journalists covering the event.

Trustees of the 612 Humanitarian Relief Fund, which helped the injured and those arrested during the 2019 social movement, were also arrested recently. The Fund has been inactive for the last several months, yet one of the trustees, academic Hui Po-keung, was arrested at the airport in May as he was about to leave the city to teach in Europe. The next day, police arrested the remaining trustees, including 74-year-old barrister and former Legislative Council member Margaret Ng, singer Denise Ho, former Legislative Council member Cyd Ho, and Cardinal Joseph Zen Ze-kiun. Zen, who is 90, is currently the oldest person to be arrested since the implementation of the National Security Law more than a year ago.

Observers note that the number of arrests had started to escalate beginning in February, with authorities oftentimes citing the most baffling of reasons. Indeed, even bubble tea shop owners have been arrested for “incitement” after allegedly smearing the government’s epidemic prevention policy on social media.

Among those also arrested early this year was social activist Koo Sze-yiu, who has terminal colorectal cancer. Koo had been planning to go to the liaison office of the Central People’s Government on February 4 to protest against the Beijing Winter Olympics. The police arrested him before he could do so on suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power.” He has since been charged with “attempting or preparing to commit” incitement under the Crimes Ordinance, the first time this charge has been used in the 25 years since the handover.

Singer Tommy Yuen, who was active in the social movement in 2019, was arrested in mid-February and denied bail for performing a song with the lyrics “Liberate Hong Kong, the revolution of our times” in a live webcast concert. He was also accused of behavior that aroused public hatred toward the police. The Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions, a pro-democracy labor group with over 130,000 members and which has been defunct for more than six months, has had key members taken away by police as well, on charges of alleged collusion with outside forces and receiving political funds.

Security before the economy

The fear is that if all these arrests were already taking place before Lee even took over, what more when he is already at the helm? Observers also point out that with Lee lacking experience in handling non-security issues, he could go more than full throttle in his supposed field of expertise, national security, to prove he is worthy of his post.

Some observers are already predicting that the economy will take a backseat in Hong Kong under John Lee. According to veteran media analyst Kevin Lau, the Central Government’s apparent need to “make a military official the chief executive” makes for an uncertain future for business in Hong Kong, at the very least.

While not discounting political loyalty and trustworthiness in choosing the city’s leader, Central authorities in the past had placed greater emphasis on the views of the business sector to maintain Hong Kong’s prosperity, as well as on the image, experience, and ability of the chief executive to inspire confidence among Hong Kong residents and the international community. The selection of the chief executive was achieved mainly through long-term observation and grooming by the Central Government. With Lee seemingly falling short of many of the supposed requirements, Lau believes that his election has a feel of being a temporary mandate, with national security aspirations overriding everything else.

Sources: The Conversation, APNews, NPR.org

In truth, when Lee was appointed to his last post, chief secretary for administration, many had noted that he was the first chief secretary to come from the disciplined forces, and with no experience in politics or other government affairs.

A secondary school graduate, Lee joined the Hong Kong Police Force in 1977, becoming police chief superintendent two decades later. According to his colleagues, Lee had already established relations with mainland officials by then while working on cross-border crime. In 2012, he was promoted to undersecretary for security and later became the first police officer appointed as secretary for security since the handover. He was a British national throughout his time in the police force but was required by law to give up his British nationality when he became an undersecretary.

Yet government insiders have told local media that John Lee was not a stellar performer at the Security Bureau. In fact, he was nicknamed “Ip Man,” which indicates he asked questions on every page. The implication is that Lee knew nothing about the overall security policy and had to ask his subordinates to explain every document page by page. When Lee announced his candidacy for the chief executive post, however, local media had his former Security Bureau boss explaining that “asking questions on every page” showed that he was serious about his work.

Lee’s expertise

But Lee was apparently outstanding in something else. In 2018, he first exercised his power publicly and banned the operations of the Hong Kong National Party, which advocates for Hong Kong’s independence.

That year, too, Victor Mallet, then Hong Kong correspondent for the Financial Times and vice chairman of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club, had his work visa renewal denied by the government. He was even denied entry as a tourist for a time, but the government refused to disclose the reasons for both of its actions.

When Zhang Xiaoming, then the director of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, revisited the incident in 2020, however, he said that the government’s refusal to renew Mallet’s visa to work in Hong Kong was a sign of the Central Government’s tightening control over the city. Speculations were rife that Mallet had earned the ire of authorities when he allowed Andy Chan Ho-tin, convenor of the Hong Kong National Party (which was then not yet banned), to speak at the club.

John Lee was in charge of visa matters at the time. The crackdown on Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement while he was security chief and then the city’s second in command could have impressed Beijing all the more.

With law enforcement as John Lee Ka-chiu’s stronger suit, some observers predict that Hong Kong’s economy will take a backseat.

Shih Chien-yu, a Central Asian relations lecturer at Taiwan’s National Tsing Hua University, says John Lee’s ascension as Hong Kong’s next leader should be seen in the context of Beijing’s vision for the city. He notes that in January this year, Beijing appointed Major General Peng Jingtang, formerly Xinjiang garrison chief of staff, as the new commander of the People’s Liberation Army Hong Kong Garrison. Shih, who is familiar with China’s counter-terrorism policy, says that this symbolizes a change in the People’s Liberation Army’s role in Hong Kong: from being an ambassador of sovereignty to the outside world to a functional role in maintaining internal stability and preventing riots.

Moreover, in March, Beijing appointed Wang Linggui, the vice president of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences who focused on Xinjiang issues and counter-terrorism research, as deputy director of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office. According to Shih, this reflects that the Central Government is treating Hong Kong as a frontier issue — just like Xinjiang, Mongolia, and Tibet — and that Beijing wants to overhaul the ruling system in Hong Kong.

Lee’s assumption of the chief executive office leaves little doubt as to the new and untrodden path Hong Kong must forge under China’s watchful eye. ●

Sophia Penelli has over 10 years of frontline reporting experience in local politics, police and security, and human rights issues in Hong Kong, and is familiar with the political situation in China.