|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the namesake son of the late dictator, will take his oath on June 30, 2022 as the Philippines’ next president, the result of an election that members of the International Observer Mission (IOM) say was “very far from fair.”

Thirty-six years ago, he and his family were forced to flee Malacañang Palace, the Philippine chief executive’s office (and, at the time, official residence), amid a People Power Revolution that later inspired similar uprisings in Southeast Asia and beyond. Now that the Marcoses are poised to return to the Palace, political analysts say that the comeback of authoritarian rule in Southeast Asia is all but complete.

Cleve Arguelles, assistant professorial lecturer of political science at De La Salle University in Manila, sees the president-elect’s family legacy as a troubling reminder to his country of the little political progress it has made since the ouster of Marcos Jr.’s father in 1986, as well as to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), where Marcos Jr. “will find himself at home” once he assumes office.

“ASEAN is looking like an autocrat’s club year after year,” Arguelles says. And with a Marcos-led Philippine government, he says, Southeast Asia’s governing elites will thrive even more in their persistent efforts to undermine democratic checks and balances on executive power, as well as to delegitimize dissent.

In 2016, Ferdinand Marcos Jr. ran for vice president and lost to Leni Robredo, who would be his biggest rival in the 2022 presidential race. Today, Marcos Jr. is president-elect, supported by people who want to bring back the iron-fisted ways of his late father. (Photo: “Pasasalamat Tour: BBM visits Mandaluyong City – 25 July 2016” by Bongbong Marcos is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.)

Then again, Arguelles adds, “Our domestic political development is part of the regional and worldwide tectonic shifts threatening the long-term durability of democracies.”

“In the past years, we have witnessed a global wave of autocratization — a surge in autocratic politics in different countries around the world, mainly through the gradual erosion of democratic institutions and norms,” he says. Referring to Marcos Jr., he notes, “The legacy of his family’s rule, as well as his refusal to acknowledge the abuses and corruption his family has committed, will sit well in our current political disposition.”

Formidable tandem

According to the academic, Filipinos are aware of their country’s own period of substantial democratic decline especially under the past six years of the government of outgoing President Rodrigo Duterte because, like many among its ASEAN neighbors, including Indonesia and Thailand, “the Philippine government has undermined media freedom, red-tagged civil society, and abused police power.”

Critics of the Marcos clan expect the administration of Marcos Jr. to be no different, not only because they believe the president-elect is surrounded by people who want to bring back the iron-fisted ways of his late father, but also because the incoming vice president happens to be Duterte’s own strong-willed daughter, Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte-Carpio.

Duterte-Carpio was actually being persuaded to run for president before she agreed to become Marcos Jr.’s running mate in the elections. Their tandem is a coalition between two of the most powerful — and most notorious — political dynasties in the Philippines.

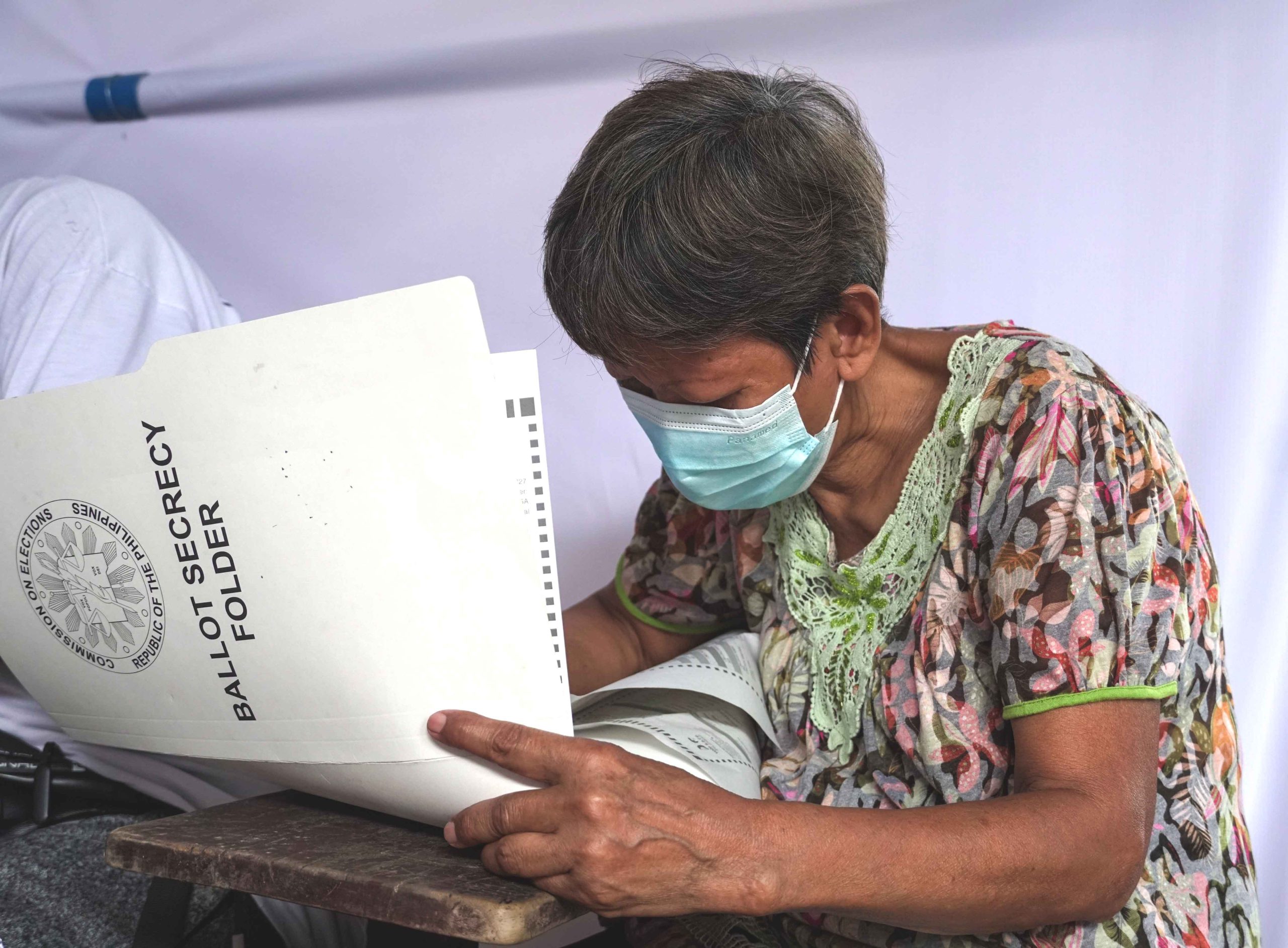

In a press release issued after a forum about the Philippine elections of civil society organizations (CSOs), parliamentarians, and human rights groups at the House of Representatives of the Belgian Federal Parliament late last month, IOM said that “the combination of economic desperation and erosion of democracy … created the conditions of the return to power of the Marcoses and the continuation of Duterte’s brand of populist demagoguery.”

Glenis Balangue of IBON Europe, a Brussels-based CSO and IOM member, was meanwhile quoted in the press release as saying, “Under this tandem, we have the worst aspects of Philippine politics — a political dynasty brought about by authoritarianism, financed massively by corruption, characterized by widespread deceit and disinformation with no coherent program for poverty alleviation, job creation, and national development.”

IOM member Wim De Ceukelaire of the Belgian nongovernment organization Viva Salud also predicted that Philippine CSOs would continue to be challenged by trumped-up charges, illegal arrests, and red-tagging under the incoming administration, as has been the case during the Duterte regime.

De Ceukelaire said, “The international community should express solidarity with the Filipino people through various ways, now that the prospects of good governance and accountability (are) extremely dim.”

Members of the IOM, which was launched in February 2022 by the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines-Europe, had gone to various regions in the Philippines to observe the elections and to provide independent monitoring of the political exercise.

Campaigning with a narrative of “unity” but without presenting an actual program of government, Marcos Jr.’s win can be said to be a combination of various factors.

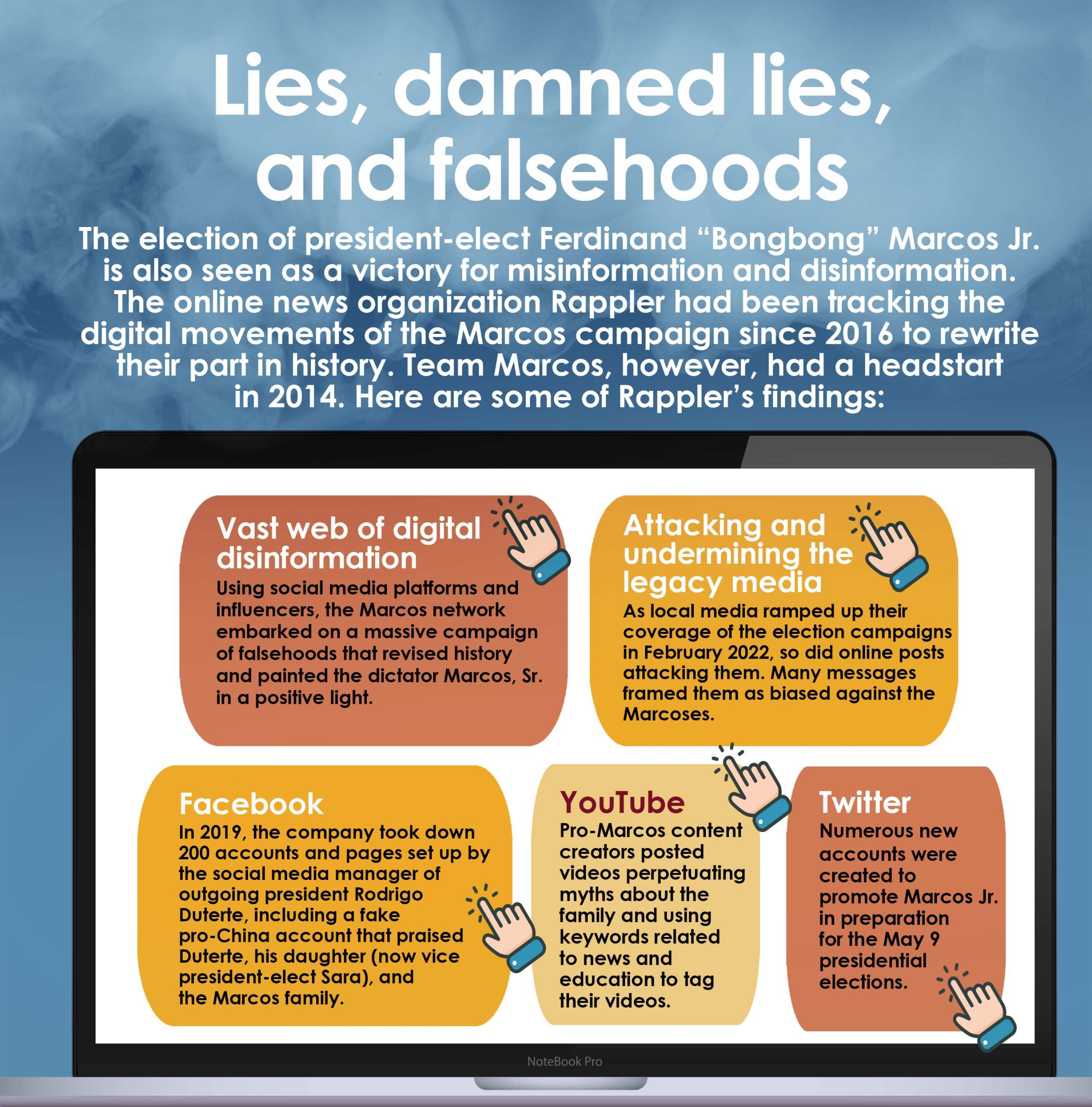

Another IOM member, Clarisa Ramos, spokesperson of the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines-Europe, for one, cited the Marcos family’s efforts to rebrand itself through social media trolling and disinformation, including distorting factual historical narratives that usually target young voters who are active on social media. Ramos also said that the Duterte government “had an active role in revamping the image of the former dictator’s family, beginning with the burial of Marcos Sr. in the Cemetery of Heroes.”

Change, but not for the better?

In a recent local TV talk show, lawyer and former dean of the Ateneo de Manila University School of Government Antonio La Viña meanwhile observed that the incoming Marcos administration is the “culmination of total elite control over the country’s political system.”

“The success of the Marcos campaign is a vindication not only of the Marcoses of the last 30 years but of also the Marcos-Duterte alliance, two families that got together,” he said.

Sources: Rappler, Media Development Investment Fund

In the same talk show, political scientist Richard Heydarian said there is a high chance that the Philippines will have a “hybrid regime of authoritarianism” that mixes a consolidation of political families and elites in a predictable government of the same old economic and foreign policies, an insensitivity to human rights, cronyism, and corruption.

“It’s a same-same situation,” Heydarian said. “Maybe the cast won’t be so different but the script could change.”

“I think constitutional change is almost inevitable,” he said. “I’m having a hard time seeing Marcos Jr. allowing himself to be confined by a Cory Aquino constitution. Things will change; they will defund the constitutional checks and balances, they will defund the Commission on Human Rights.”

The widow of assassinated former Senator Benigno ‘Ninoy’ Aquino, the late Corazon “Cory” Aquino was the immediate successor of Marcos Sr. The 1986 People Power Revolution was sparked in large part by Marcos cheating her in the February 7 presidential snap election that year. The Cory Aquino government, during which the 1987 Constitution was written, marked the restoration of democracy in the Philippines.

Heydarian said that the most likely outcome for the Philippines in the coming years is that “we’re gonna be more like Hungary or Malaysia, where you have elections that, you know, will only legitimize the ruling coalitions. It could be Marcos Jr., it could be Sara Duterte, the same kind of people, and it’s very possible under a new constitution.”

With disinformation and the huge efforts to decimate the traditional and legitimate media as the new challenges, both La Vińa and Heydarian said that fighting disinformation needs to be ramped up and the country’s opposition has to reinvent itself in the coming years to bring back the trust of people in a liberal democracy.

A senior Filipino casting her vote on election day, May 9, 2022. Members of the International Observer Mission note that “the combination of economic desperation and erosion of democracy … created the conditions of the return to power of the Marcoses and the continuation of Duterte’s brand of populist demagoguery.”

For sure, just a generation ago, there seemed to be little chance that people would forget the rapaciousness of the Marcoses and their cronies, which rendered the country bankrupt even as they amassed billions of dollars. The older Marcos also used brute force to suppress political rivals and critics, including student activists and journalists.

Yet today, the Marcos campaign that used social media influence appears to have already had considerable success in “rewriting” the Martial Law years and the Marcos regime narratives, including the 1986 People Power revolt. That alone had Heydarian conceding that he is not certain how the next years will unfold. Still, he said, “this is nothing unique. We see this trend all around the world.”

“In the case of the Philippines, at least we had 30 years before another Marcos came back into power,” Heydarian said.

Then he asked: “But what did we do in (those) 30 years?” ●

Diana G. Mendoza is a freelance journalist based in Manila.