|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

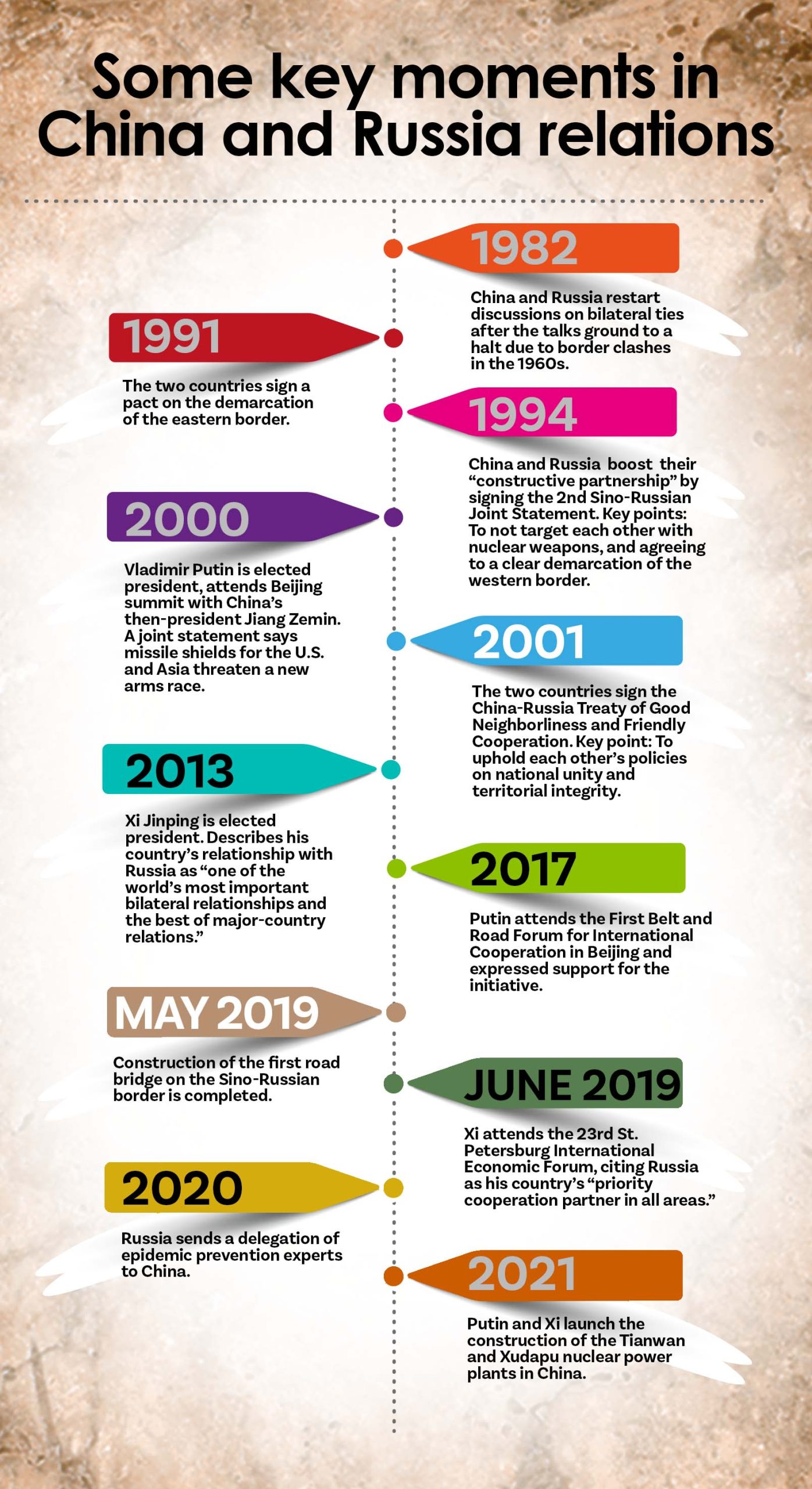

On Feb. 4, 2022, or 20 days before the Russian military offensive into Ukraine was launched, a long meeting transpired between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin in Beijing. Following this meeting — which did not go unnoticed by Western powers — the two leaders who have positioned themselves as strongmen released a statement in a show of solidarity. Among other things, the statement underscored a strengthening of bilateral relations in a “no limit” strategic cooperation, which included Russia’s recognition of Taiwan as Chinese territory and, reciprocally, China’s endorsement of Russian opposition against the expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Given the timing of the meeting and the resultant statement, speculation about the Chinese leader having had prior information about the planned Russian military invasion of Ukraine has been rife within diplomatic circles. Then again, that would be no surprise. The Sino-Russian relationship is one that, despite its many ebbs and flows, has endured in some way or form over the past decades.

The neighbors that share the longest land border in the world have, in recent times, found many areas of convergence and cooperation. For example, when the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre resulted in a freeze in Sino-U.S. relations, China was forced to turn to Russia for its military needs. Today China receives 77 percent of its military goods from Russia, making close ties with Moscow an integral part of the Chinese defense architecture.

Chinese President Xi Jinping (right) welcomes Russian President Vladimir Putin to the G20 Summit in Hangzhou, China in 2016. The ties between their two countries go a long way back and continue to endure today.

Similarly, when Moscow’s relations with the West declined sharply as a result of Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, it looked toward China for cooperation in a newly rejuvenated way as an ally rather than just a trade partner. This new cooperation was heralded in 2015 with the two countries pledging cooperation between both their transnational ambitions: China’s Belt and Road project and Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union.

These days, as Russia’s war with Ukraine grinds on, China has maintained what many have referred to as “pro-Russian neutrality,” a stance that ostensibly hopes to maintain newly-reinforced political and economic relations with Russia while also avoiding souring relations with Western powers. Yet while Beijing may be expected to stay by Moscow’s side for as long as the conflict continues, that could well be all it will do in support of the Russian action.

Shared anxieties

Common resistance to the Western ideology of supranational value systems and what is perceived as neo-imperialist ambitions have diplomatically joined the two powers, even as their domestic social orders differ vastly. These make the likelihood of a Sino-Russian relationship enduring high. Both China and Russia share anxieties regarding the intentions of Western powers, which are perceived to be intrusive and self-serving. While Moscow might also have reason to fear its fast-growing neighbor that has an economy more than six times its own, it does understand the value of good neighbors whose ambitions do not include intrusions into its own sovereignty or governance.

Given this context, it was not entirely unexpected to witness the Chinese abstention on the UN Security Council vote that sought to condemn Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, being coupled with a reinforcement of the Russian narrative of the United States as the aggressor, that created conditions that left Russia with little choice but to launch a military offensive for the very reasonable goal of protecting its borders. Shortly after the invasion was launched, China’s foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying even made a remark that has since been read as signifying an amplification of the Russian narrative as well as China’s own position with regard to allying with Russia.

Hua said, “All parties should work for peace instead of escalating the tension or hyping the possibility of war. Those parties who were busy condemning others, what have they done? Have they persuaded others?”

Placing the blame firmly on Washington’s shoulders, China has been unequivocal in its condemnation of economic sanctions imposed upon Russia by Western powers with the aim of crippling the nation. This position created fears in Washington of possible Chinese military and economic assistance extended to Russia in its conflict with Ukraine — an eventuality that has not yet transpired, much to the relief of the Western bloc.

But while the United States might continue to exert pressure on China, advising it to think twice before extending a helping hand toward Russia, there is certain circumspection among policymakers in Washington that hopes not to antagonize the world’s second-largest economy and one of the biggest holders of U.S. dollars. After all, according to Dr. Steven Tsang, director at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies China Institute, China and Russia have a common ideological goal “to make the world safe for authoritarianism so their hold to power is safe in their respective countries,” and also “to weaken the Western alliance led by the U.S.”

Despite its rising power and influence on the world stage, China itself is acutely aware of the United States’ still-intact hegemony and Beijing’s need to balance strategic relations with both Russia and the Western powers in order to safeguard its own interests. Yet while a furious U.S. President Joe Biden has referred to Putin as a “war criminal” and “butcher,” China has extended undeniable tacit support in helping augment certain Russian narratives such as refusing to refer to the conflict as a “war,” choosing instead the Russian term “special military operation,” as well as amplifying a Russian accusation that claimed the United States was producing bioweapons in Ukraine, which was later found to be false.

Many of the Russian narratives regarding its reasons for invading Ukraine do, in large part, lie in parallel with Chinese anxieties on the global stage, making it easy for China to defend the narratives. For instance, Russia’s concerns regarding the expansion of NATO eastward and the discomfort resulting from being encircled by Western powers find resonance in China’s fears of the United States becoming more active in its security architecture. But Russia’s second narrative, which claimed the purpose of the invasion to be de-Nazifying Ukraine found less traction in Chinese discourse, owing in some part to their own close economic association with Ukraine and, in some part, their discomfort with the problematic “right to protect” argument, which conflicts with Beijing’s unwavering stance on sovereignty.

The threat to Taiwan

At the beginning of Russia’s invasion, global strategists were in a flurry over the possibility of China launching a similar offensive into Taiwan. Believing China’s stance on the invasion in Ukraine to be in part drawn from similar aspirations regarding Taiwan, U.S. strategists were spurred into developing a plan should China follow in Russia’s footsteps.

Although it now appears unlikely that China, discouraged by Russia’s poor military performance in Ukraine, would move to take Taiwan at this point, it is fair to surmise that it would be watching events in Ukraine unfold with keen interest to determine the scale of expected blowback if events in Taiwan were ever to come to the same crossroads. How long the Russian-Ukrainian conflict will drag on also matters. The longer it takes, the more consolidated anti-Russian allies will find themselves, a bloc that might be motivated to meet Chinese ambitions of “liberating Taiwan” in much the same way.

It would be ill-advised for China as well to find itself in a military standoff with the militarily superior United States, which would also pit it against the European Union by extension, disrupting global trade, supply chains, and international world order, and damaging its relations with the Western powers, perhaps irretrievably. While annexing Taiwan might earn China brownie points in the homeland, it would certainly harm its diplomatic standing on the global stage, a risk that China does not appear to be willing to take in view of a weakening Russia and an increasingly aggressive United States.

China has always been cognizant of the delicate balancing act that is required from a world power that has aspirations to one day become the world hegemon while simultaneously preserving national interests. It was in the interest of maintaining this balance that China, while abstaining from voting on the proposed referendum after Russia’s annexation of Crimea eight years ago, also did not recognize the annexation. This was in keeping with its international diplomacy of non-interference, as well as a hesitation based on distrust of the West. It is also why while it amplifies Russian rhetoric now, it has moved to provide humanitarian aid in Ukraine.

Though China has not indicated any active support toward the invasion into Ukraine in terms of military or economic assistance, it certainly would stand to gain from a successful Russia, which would owe it loyalty, and a weakened Western bloc. However, it is also worth noting that China is only likely to gain this diplomatic power if Russia is victorious in a way that does not allow for severe retaliation from Western powers that would serve to cripple it. As the war draws on and reports of a struggling Russia solidify amidst worsening economic sanctions, China’s position grows more and more tenuous.

Ukrainian soldiers in Kharkiv preparing for an attack by Russian forces in January 2022. China has maintained what some call a “pro-Russian neutrality” that may help maintain its political and economic relations with Russia.

Within China as well, Russia’s failures might become a domestic liability for Xi Jinping, forcing Beijing to acknowledge the limits of the Sino-Russian “no limits” friendship. As firm as China’s stance in its friendship with Russia is, it has also clearly refrained from extending the level of support that Russia would ideally want from its ally. This makes it clear that at the end of the day, China might throw Russia a buoy or two, but is unlikely to share its own raft. ●

Insiyah Vahanvaty is a socio-political commentator with an interest in minority rights, human rights, democracy, gender parity, and secularism.