|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In Pakistan, systems are destroyed to save egos from being bruised. A battle of egos and wits is unfolding yet again as the government puts its foot down to take the toughest measures and impede possibly yet another Azadi (freedom) March being summoned by Imran Khan. The recently ousted premier is hellbent on undertaking a long march to force the government to announce a snap election. He has also warned that the country will “break into three parts” if “the establishment doesn’t make the right decisions.”

Making the remarks during a recent TV interview that has since been widely quoted, Khan also said that “if the right decisions aren’t made at this time, then the country is going toward suicide.” It appears, however, that it is a murder that is taking place, and the culprits are those lusting after power and the people who currently have it.

Indeed, in Pakistan’s never-ending game of thrones, the electorate is always the first and the worst victim, abused on multiple fronts due to the self-serving ploys of political parties and politicians that damage democracy and flout the Constitution. The political hysteria of the last few months has inflicted indelible wounds on the electorate, with the Charter compromised and institutions maligned, while pillars of the state seemed to be on a catastrophic collision course.

Workers from Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, the political party founded by the former Pakistan prime minister Imran Khan, continue to show support for Khan even after he was ousted from his post via a no-confidence vote in April 2022.

“At the end it’s at the altar of parliamentary democracy and human rights that political cults grow and dynastic politics of all political stakeholders flourish,” remarks Shirah Zia, an Islamabad-based political analyst.

These days, Pakistan’s already blemished democracy, captured and co-opted by civilian and non-civilian elites, is going through another inflection point. Most likely, what will emerge will be of little use for most of Pakistan’s more than 240 million people.

Today Pakistan has an economy devastated by the previous government’s populist choices, while the government of the day is reluctant to make unpopular decisions for fear of electoral losses and lost popularity in the elections next year. But while populist economic decisions save political careers, they push public lives into deeper pits of imminent misery.

Inflation hit 13.76 percent in May 2022, the highest in over two years. Petrol prices have seen a significant increase, with cooking oil prices witnessing an unprecedented PKR 213 (US$1) hike per liter just as June began. So far, Pakistan’s talks with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have gone nowhere, with the lending institution saying that the country has to take “wide-ranging steps to repair macro-economic stability.”

Pakistani households will continue to be burdened by foreign and domestic debts that mount and multiply under populist “relief” packages, including the cut on petroleum and power prices by the previous government and the current government’s hesitation to withdraw the subsidies. A recent editorial in a leading local English daily thus read: “Eventually these debts will have to be paid back, with interest and enormous currency depreciation. Reneging on agreements with the IMF, cutting taxes when in fact the agreement was to increase them purely for political gains, means that the IMF would place even more difficult preconditions on Pakistan when it needs a further bailout.”

Politics without problem-solving

The present regime’s inertia regarding tough economic decisions is only worsening the people’s economic losses. It will mean even more suffering for millions of households across the country in the coming months. With all focus converging on economic development though, social development indicators like losses to education and health are ignored, even as individual freedoms and rights are suffocated. Worse, a massive brain drain seems to have made intellectual capital scarce in Pakistan, and whatever is left is always leveraged for political maneuverings and political battles rather than solving actual problems.

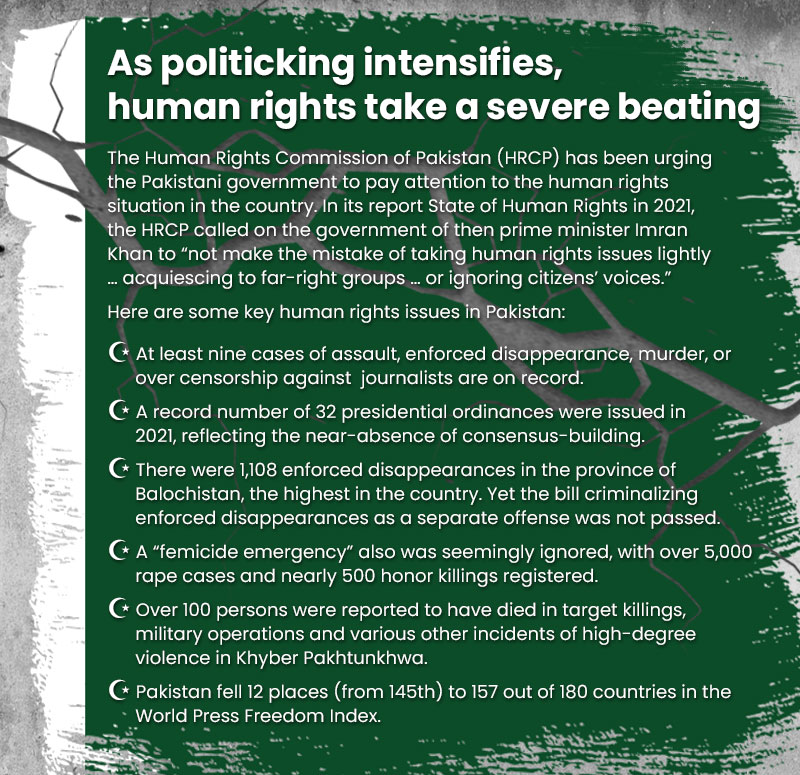

Just this April, the non-government Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) released its 2022 report, which paints a sorry picture of how political battles rooted in vested interests impair an already unenviable human rights record. According to the report, 2021 witnessed innumerable rights violations in the country, as solipsistic political moves sidelined all concerns for the people’s welfare.

The previous government, for instance, had failed to get the long-awaited enforced disappearance bill passed as a separate autonomous offense, despite having promised to do so after coming to power in 2018. In fact, amid ambiguities surrounding the tabling of no-confidence motion against then Prime Minister Khan last March, there had been a protest taking place just a few miles away from Parliament. The sit-in, organized by Baloch students, called for the release of Hafeez Baloch, who was reading for his master’s when he disappeared in February 2022.

But Baloch’s disappearance was only one of the thousands of disappearances. Balochistan had the highest number of “enforced disappearances” in 2021, according to the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances; Khyber Pakhtunkhwa had 1,417, the highest number of “pending disappearance cases.” So far this year, the commission says a total of 158 individuals have been reported missing.

A Pakistani woman cast her vote in the 2016 elections. Observers note that the political hysteria of the last few months has inflicted indelible wounds on the electorate.

Activist youths are not the only ones who become apparent targets of whoever is in power, however. The use of intimidating tactics and unwarranted search raids against opponents by those in power is not unusual in Pakistani politics. Arbitrary raids, seizures, and detentions have been employed as tools by elements within the state for “objectives” that they may not be able to achieve through legal channels. Just recently, former human rights minister Shireen Mazari was arrested by Islamabad police outside her home on the directive of the Anti-Corruption Establishment, but released later on the order of the Court. Meanwhile, the homes of dozens of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf leaders and activists were raided in the middle of the night as a pre-emptive measure to deter Khan’s long march on May 25, 2022.

Members of the media have been caught in the crosshairs of the state as well. The HRCP report narrates how journalists were intimidated or silenced in nine different cases in 2021. It observed, “The state’s attempts to expand the scope of restriction on freedom of expression under Article 19 of the Constitution have emboldened non-state actors to impose their whims often violently on those who do not agree with them.”

Today, the powers that be are different, but the actions are the same. Since gaining control of the government in April 2022, the current Shehbaz Sharif administration has already filed sedition cases against at least four journalists.

The findings in the Freedom Network’s latest annual report echo this pattern, with the state and its functionaries ranking as the “biggest threat actor” targeting media in Pakistan. The state was the suspected perpetrator in a whopping 41percent of at least 86 attacks against the media and its practitioners that the organization recorded between May 2021 and April 2022. Another significant finding was that the nation’s capital, home to some of the most secure locations in Pakistan, proved to be “the riskiest and most dangerous place to practice journalism.” The province of Sindh was the second-worst in this category.

More rights violations

In the chapter on Pakistan in its 2022 World Report, Human Rights Watch (HRW) points out that extrajudicial actions carried out by state actors have a chilling effect on voices critical of policies favored by powerful blocs within the state. It also stressed, “They violate fundamental freedoms guaranteed in the Constitution.”

HRW’s chapter on Pakistan focused on freedom of expression and religion, women’s rights, and alleged abuses by Pakistan’s police and security forces. In truth, when it comes to the violation of freedoms in Pakistan, women know them firsthand far too well. Comments HRW in its 2022 report, “With 5,279 rape cases and 478 honor killings and the macabre murder of Noor Mukadam in Islamabad, women’s rights activists speak of a ‘femicide emergency’ in Pakistan in 2021.”

Many Pakistani women are subjected to domestic violence and brutalities by people they know, yet legislation against domestic violence was rejected by the Council of Islamic Ideology last year, based on its skewed interpretation of the law. The council also opposed a bill on forced conversion, despite the abduction and conversion of young, non-Muslim women and girls remaining a major rights issue.

In the meantime, Unequal Citizens: Ending Systemic Discrimination Against Minorities, a report compiled by the National Commission for Human Rights with support from the European Union, reveals that half the posts reserved for religious minorities in government jobs are vacant. Eighty percent of the non-Muslims who have been appointed under the five-percent quota for them are also working in low-paying sanitation jobs.

April 9, 2022 witnessed a disgraceful exit from office by a leader who, up till now, has yet to stop lecturing the public on the pitfalls of Western democratic values and morality, while his populist, ultra-nationalist rhetoric galvanized supporters to march for supposed freedom last May 25. Imran Khan himself put an abrupt end to the march hours after it began, supposedly to avoid further bloodshed after at least two people were killed and scores injured. But some observers said that he only wanted to save face, after managing to gather just thousands when he expected millions of people. Khan has since said that another long march may come and that “this time the party will come prepared.”

Meanwhile, all of the country’s political elites will remain engaged in their political machinations for weeks, seeking a greater share of a rotting pie to which they have reduced the affairs of this country. ●

Faryal Shahzad is a freelance journalist, entrepreneur, and academician.