|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

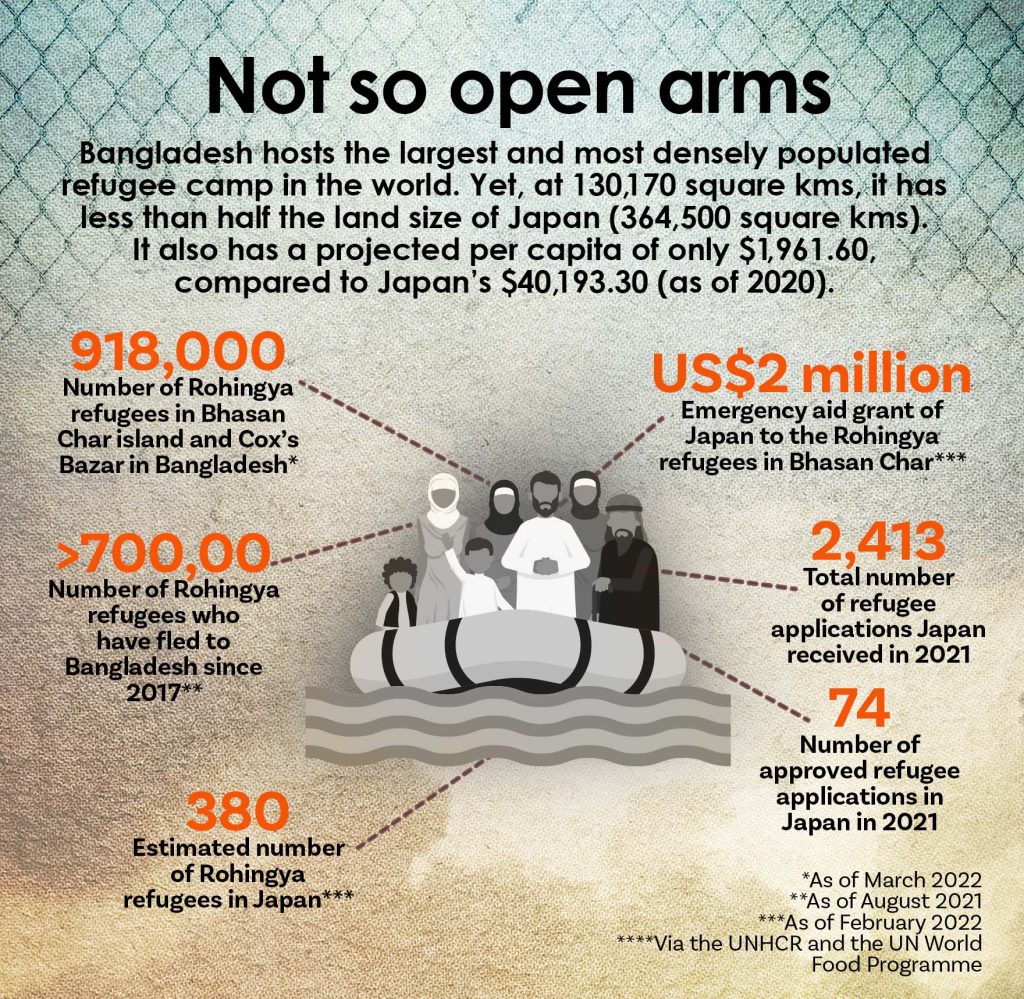

For the approximately one million Rohingya crammed into teeming refugee camps in Bangladesh, Japan is a most generous donor. In January 2022, Japan extended emergency aid of US$2 million for the Rohingya who were moved by Bangladeshi authorities to the island of Bhasan Char. It was the first country to offer financial aid for the new refugee community there. From 2017 to the present, Japan has given more than US$120 million for the Rohingya seeking shelter in Bangladesh, which is just next door to their homeland, Myanmar.

However, Japan itself does not seem keen to host refugees, Rohingya or otherwise. Its low acceptance of refugees — two percent of applications annually or just 84 in 2020 — has put the country at the bottom of the ladder in accepting people fleeing war and human rights abuse in other countries. In comparison, Germany, an important destination for refugees, has an acceptance rate of over 50 percent annually.

“Japan is so popular with the refugee community in other countries due to their generous humanitarian assistance,” comments Zaw Min Htut, head of the Burmese Rohingya Association in Japan (BRAJ). “But it is different when you come to Japan to seek asylum. We did not know before that they have a double standard regarding the refugees. They help refugees in other countries, but they are very much reluctant to accept refugees in Japan.”

Zaw himself was enticed by a travel agent to try seeking asylum in Japan decades ago when, as one of the participants in Myanmar’s 1990 student protests, he was forced to flee his homeland. But Japanese authorities were quick to spot his fake travel documents, and he spent his first month in Japan languishing in solitary confinement. He would remain in detention for months more until rights advocates and lawyers came to his aid.

Many Rohingya refugees from Myanmar who were crammed into refugee camps such as this one in Cox’s Bazar were moved to the remote, cyclone-lashed island of Bhasan Char. Japan was the first country to offer financial aid to the refugee community there.

Now 50, Zaw has become a naturalized Japanese citizen. He says, “My success was dependent heavily on the support I received from my Japanese lawyers and human rights activists. It was an uphill battle for me in Japan despite the clear evidence of the military junta strategy to wipe us out through violence.”

The Rohingya are an ethnic minority Muslim community whose members live mostly in Myanmar’s western state of Rakhine. For decades now, they have endured institutionalized persecution in the predominantly Buddhist country. In 1982, the Rohingya were stripped of their citizenship rights when Myanmar promulgated a new citizenship law that essentially made them stateless.

Although they had been subjected to sporadic attacks by the military and sometimes by ethnic Arakanese for years, a massive military attack in 2017 had the Rohingya fleeing for their lives by the hundreds of thousands. Most of them ended up in neighboring Bangladesh, where some 300,000 Rohingya had already sought refuge after previous attacks. A few are now in Japan.

When asked why the Rohingya would choose to seek asylum in Japan, Zaw points out, “Japan is the biggest democratic country in Asia that officially accepts refugees. Japan has also been helping the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh with food and other things since 1978, so the Rohingya think Japan would be (good).”

Slow-moving process

Slow-moving process

At present, the Rohingya in Japan number around 380. Most of them live in Tatebayashi, Gunma prefecture, a mountainous region 96 km northwest of Tokyo. Less than half of the Rohingya have been granted Japanese nationality; the rest are permanent residents or have short-term visas. Many of them work in local factories providing valuable labor for small and medium-sized manufacturing companies that are shunned by the Japanese for their demanding long hours and low pay.

Some Rohingya, though, have started trading companies involved in the export of second-hand vehicles to Asia or importing Asian foods. Haroon Rashid, 61, is one such Rohingya businessman. A founding member of BRAJ, which was formed in 1994, Rashid gained Japanese citizenship after living 10 years on refugee status. He now owns several small stores in Tokyo and the outskirts and employs Rohingyas.

“Life in Japan with my family is not difficult now,” he says. “The community helps each other.”

Then he adds, “Another important role for us is to lobby the Japanese government to recognize the genocide against our community in Burma (as Myanmar was previously known).”

Western countries have publicly accused the Myanmar military junta of human rights violations against ethnic minorities, and especially the Rohingya. Nobel Peace laureate and now deposed Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi even lost much of her global popularity when she refused to condemn the military’s brutal attacks on the Rohingya. Hearings pertaining to the Myanmar military’s atrocities against the Rohingya have been held at the International Court of Justice since 2019. In March 2022, the U.S. government officially recognized the latest atrocities against the Rohingya as crimes against humanity and “genocide” — a declaration unsurprisingly rejected by the Myanmar military government.

According to human rights lawyer Shogo Watanabe, Japan’s official recognition of the Rohingya represents a dilemma for Tokyo, which is mindful of the large business interests of Japanese companies in Myanmar.

But he says, “The atrocities committed against the Rohingyas are accepted worldwide. The Japanese government must urgently recognize this fact, a step that will make it easier to officially extend refugee status to them in Japan.”

During the last three decades, Japan has recognized only 24 of the 130 refugee status applications it received from the Rohingya. Others on the list have been extended humanitarian visas that permit them to reside on long-term or short-term stays. There are also Rohingya who live without legal status that denies them the right to work — some of them for the last 20 years — and they are able to survive only through the support of the small Rohingya community in Japan and other organizations.

BRAJ leader Zaw is an open critic of the Japanese government’s foot-dragging on pressuring the Myanmar military to stop its genocide against the Rohingya, of whom there are still 600,000 left in Myanmar.

“We have visited the Foreign Ministry several times to explain the suffering of our community and the importance of Japan officially recognizing (what the military is doing to the Rohingya) as genocide, just like the United States,” Zaw says. “But they only believe (what) the Myanmar government tells them.”

Sources: World Food Programme, UNHCR, Japan Association for Refugees, Victoria University of Wellington, UN OCHA, World Bank

Retooling the rules

The lack of documents such as passports and birth certificates and even COVID-19 vaccination certification to support their applications are the main challenge for the Rohingya seeking refugee status in Japan. But activists have long pointed out that people fleeing conflict and genocide cannot pass this strict screening.

Under international pressure, Japan began accepting third-country settlement programs. However, since 2015, it has seen the arrival of only three Rohingya families from Malaysia. The program, though, was temporarily suspended in 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic; it has yet to be restarted.

Japan is now in the throes of passing a bill to amend the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act, focusing on determining the applicants’ eligibility. But rights advocates are challenging the amendment that, they note, does not address limits regarding the detention of asylum seekers. According to the activists, Japan needs to adopt a consistent refugee policy based on humanitarian principles.

Recently, Japan began accepting Ukrainians fleeing Russia`s invasion of their country — which turned the spotlight all the more on the discrepancy in the treatment Japan offered to refugees from different nations. In contrast to their slow processing of refugees from other countries, Japanese authorities swiftly granted more than 600 Ukrainians legal status as evacuees; the Ukrainians also received official and private financial support for their resettlement.

Zaw recalls that when he fled Myanmar, he first went to nearby Thailand, where he spent his days in hiding before a travel agent suggested that he try his luck in Japan. He says that his family back home was well-off and that, as the eldest son, he was expected to do well. But being a Rohingya meant that for all his relative good fortune, the odds were still stacked against him right from the start. As a Rohingya, for example, he was barred from pursuing medicine or law. Yet Zaw somehow managed to be accepted to a master’s degree program at the zoology department in the elite Rangoon University in Yangon.

Then the students’ protests began and a crackdown ensued.

Life in Japan for many Rohingya refugees from Myanmar is far from settled. Japanese authorities meet with the Rohingya refugees in the Gunma prefecture (left) while Rohingya children attend class in a makeshift school established by the Burmese Rohingya Association in Japan.

“My survival is a testimony to the uphill task the Burmese Rohingyas must face to live as people whose rights are respected,” Zaw says. “Tens of thousands of displaced Rohingya are desperate to find a way out of their bleak futures. I work hard to support them.”

Starting life again at 26 years in Japan has been, in the end, a good decision, Zaw says. In 2009, he started his own trading company. He is married to a fellow Rohingya who he met in China. They live in Saitama, close to Tokyo. Their children go to local schools and have adjusted well. Along with his friends, Zaw supports a school for refugees living in Bangladesh. They have also built a mosque in Tatebayashi.

Yet after all this time Zaw still hopes to return to Myanmar one day — even though he says it has been burnt down. “Everybody I knew has fled to safety,” he says, “but this does not mean we have forgotten our roots.” ●

Suvendrini Kakuchi is a Sri Lankan journalist based in Japan, with a career that spans almost three decades. She focuses on development issues and Japan-Asia relations.