|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Duyên was on pins and needles for months. Her only son Vũ had been called to perform military service, and she was not keen to let him go. Duyên thought it would disrupt Vũ’s pursuit of undergraduate studies, which had already been delayed for three years while he tried to figure out what he wanted to do. She had also lost her own father in the war, contributing to her dim view of military life.

After consulting with other mothers in her village, Duyên learned that a one-time postponement would cost around VND 3 million or US$130. The more money is paid, the longer one can delay serving in the military.

Duyên had a meeting with the village leader, who served as the middleman between her family and those in charge of recruiting draftees. In the end, a deal was struck: Duyên paid VND 20 million or US$870 in full for eternal deferral. In other words, Vũ would never again be called up for military service.

“I had to borrow money from here and there to support him,” said Duyên who, like all the others interviewed for this story, uses a pseudonym. “That is an investment. I cannot bring myself to see him waste two years of his youth in the army.”

After graduating from high school, many Vietnamese students prefer to go to university and avoid the mandatory two-year conscription. Paying local authorities to dodge military service is an open secret.

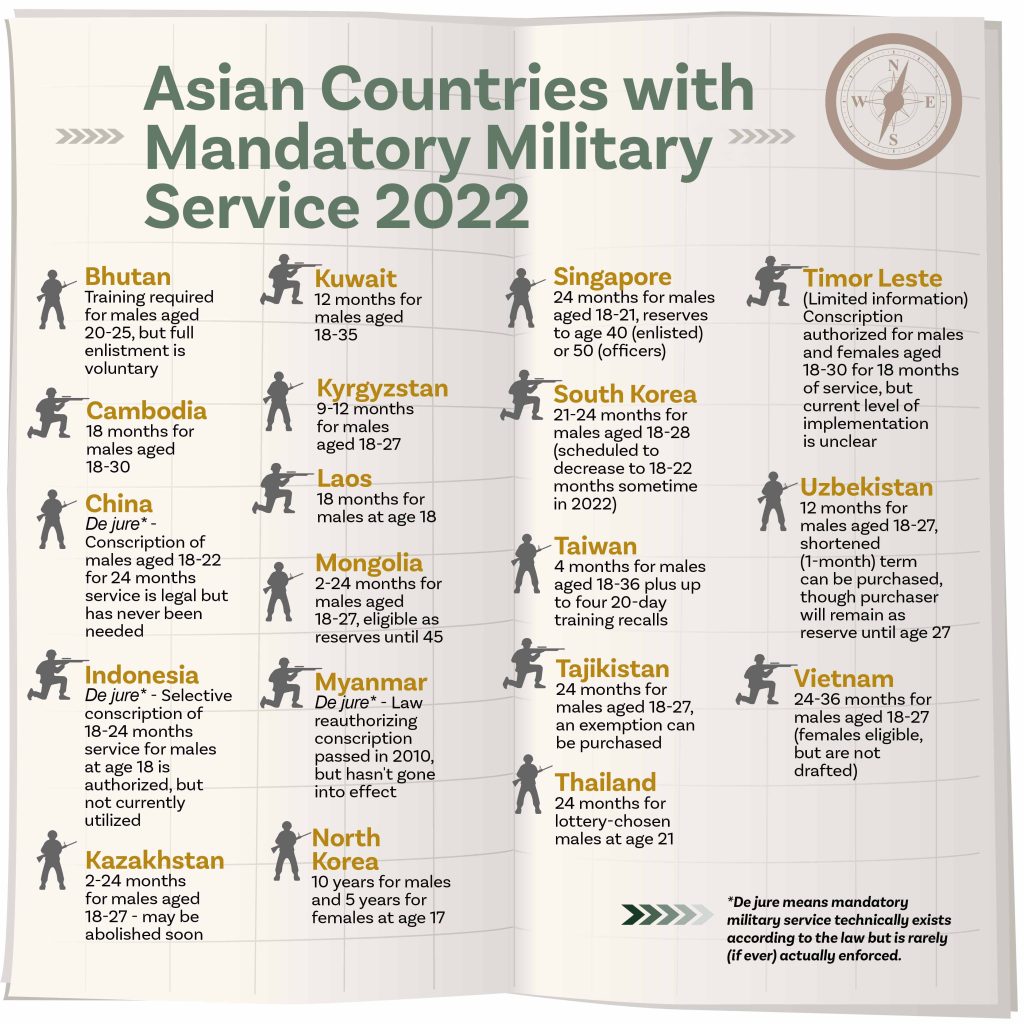

Since 1975, a two-year conscription has been mandatory in Vietnam for male citizens between the ages of 18 and 25; it is totally optional for women. But with the country needing human resources for economic development, those qualified for university after passing the fiercely competitive national entrance exams are allowed to postpone fulfilling the service. Full-time college students can thus legally defer enlistment until they graduate. Then until they reach their 27th birthday, they join those who have similarly postponed military service and who are on the queue for the call to be part of the armed forces.

Ignoring conscription call-ups is subject to fines, while draft dodgers can face up to five years in prison. Unlike in other countries, military and public security service in Vietnam cannot be replaced by social service.

It is an open secret, though, that young men or their families pay local authorities to dodge military service. And despite occasional reports on bribery for draft evasion, there has been no systematic fight against the corrupt practice that gives way to draft evasion at local levels.

Money equals deferment

Draft evasion and desertion are hardly new in Vietnam. In the 1980s, there were draft evaders and deserters who were reportedly sentenced to re-education or to labor and construction work in remote areas and in Laos.

These days, domestic media outlets have reported that wealthy families bribe authorities to get their children out of the draft. But draft evasion is not necessarily done just by the well-to-do. Vũ’s mother Duyên, for example, is a garment factory worker who makes just enough for her family to get by.

Then there are the likes of Long, a software developer whose employer, a state-owned IT company, made the arrangements for him and those among his colleagues who are “potential draftees” to push back their call-up dates.

The nearly all-male company apparently needs skilled youngsters to expand operations at home and abroad, and so it has been collecting “dodging fees” from all its male staff members under 27. The company then sends its human resource officers to deal with bureaucratic burdens on their behalf.

According to Long, they have each been paying the equivalent of US$150 a year, a sum that covers complete exemption from medical exams. Long said he would have to keep paying the same amount annually until he turns 27.

But he doesn’t mind. Said Long: “I do not want to be drafted. I do not want my career to get stuck for two years. I am ready to pay higher (fees) to escape from this duty.”

Bribe-giving, however, does not always guarantee successful military evasion. In 2020, a local official in Khánh Hoà province who was in charge of recruiting new draftees was arrested for collecting VND 69 million (US$3,000) to help sons from six households evade the draft. While media reports did not say if the young men and their families were arrested as well, it was revealed that the official had just pocketed all the money and did not deliver on his promise.

A career deal-breaker

The number of recruits varies from city to city and from town to town. This year, Hanoi sent off about 4,600 young men to military and public security service. Lang Son, a northern city, has 1,250 residents headed for military service and 244 more participating in the public security service.

New recruits are mainly between the ages of 18 and 25, with many being either underachieving students or coming from poor rural areas who cannot afford to dodge the draft. Indeed, it is interesting that one media report, however, made it a point to say that of the recent recruits from Hanoi, 43 percent have higher educational attainment.

Like Long and Vũ, many draft dodgers find military service a hindrance to their careers. It also hasn’t helped recruitment efforts that the reputation of the Vietnamese military, once basking in the glory of its wartime achievements, has lost its luster in recent years. Repeated mismanagement and rampant rent-seeking have slowed down the modernization of the Vietnamese armed forces, making military careers far less attractive to ambitious young men.

Excerpted from Countries With Mandatory Military Service 2022

But many also try to avoid the draft due to fear of violence and hardship in the barracks. Recent reports of the deaths of several young soldiers and the ambiguous responses of the military have only further fanned such fears some more, aside from causing uproar on the internet.

In June 2021, for instance, 19-year-old recruit Trần Đức Đô was found dead at the training field of a military school in Thai Nguyen province. Though his head, face, back, and chest showed injuries, the Criminal Investigation Agency said that he had suffocated by hanging himself, after just a very quick probe.

Not long before his death, Đô had told his family that he had been bullied in the military. The family contested the official findings and wanted an autopsy to be performed. The military, however, insisted on proceeding quickly with the funeral.

Five months later, another public outcry was prompted by the death of Nguyễn Văn Thiên, a 23-year-old soldier from Gia Lai province, and the inconsistent initial reports from the military on how he died. At first, his sudden death was ascribed to a fall in the barracks bathroom. Then, the province’s military command was quoted as saying that he had been attacked by his fellow soldiers. State media reported later that he had been “beaten to death by his comrades.”

Before 2021 ended, yet another young conscript death was reported, this time by “fighting among soldiers.” Hoang Ba Manh was just 20 years old at the time of his death.

“Unfit to serve”

No wonder then that there are parents who actually rejoice over their sons’ medical problems, however slight, hoping that these would get them off the draft. After all, the 2015 Law on Military Service says that those who are not in good health are exempt from conscription.

This has led to some potential recruits paying medical doctors to certify that they are not physically fit to join the military. Apparently, the threat of being made to pay a fine that can range from VND 2 million (US$88) to VND 4 million (US$172) for both the briber and bribe-taker for fake medical results to escape military service is not enough of a deterrent for them.

In truth, the law does not really define the conditions a potential conscript should have to be exempt. One neighborhood leader told Asia Democracy Chronicles that a condition like shortsightedness may not be enough to be excused from the draft. Besides, said the leader, “if there are not enough draftees, they would recruit shortsighted people as well.”

Đông, a young graduate who has just started working for a big international company, says, “We are not allowed to have a copy of medical results, so my eligibility depends on their whims. It is better to just pay and be left alone.”

He said that he had opted to pay VND 10 million (US$440) for a one-year deferment of his military service. “It was already tough to find a job during the pandemic,” Đông said. “I have a hectic schedule. I cannot just leave my work for medical exams.”

Young Vietnamese recruits listen to a lecture on history. For some men and their families, bribing their way out of conscription does not always work.

Tuấn’s family, though, was confident that he would not be drafted because he has been suffering from astigmatism since his early childhood. They thought his blurry vision would result in his failing the military’s medical exams. To their surprise, though, he was listed among the 2020-2022 cohort of draftees.

“Had I known that astigmatism would not exempt him from the draft, I would have bribed doctors to help him stay home,” said his mother, Hà. “The army is not a nice place to be part of.”

Realizing that it was too late to make money talk officials out of drafting her son, Hà decided to use personal connections on top of a bribe to at least have Tuấn transferred to a location near Hanoi after a year of service. That way, she said, she could visit her son more frequently. A week after the request was made, Tuấn was transferred to a location near his family home.

While Hà acknowledged that Tuấn became self-disciplined and self-reliant after the two-year service, she said that she would still have wanted him to stay home and advance his career.

“He is now lagging behind his peers,” she said. “He will have a lot of catching up to do.” ●

Nguyện Công Bằng is a contributor from Vietnam.