|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The end of the Muslim month of fasting is usually marked by feasting and celebration. But in many Muslim communities in India, this year’s Eid al Fitr was quiet and tinged with wariness.

In Khargone, in the western state of Madhya Pradesh, a curfew remained imposed on May 3, 2022, the day of Eid, three weeks after communal violence broke out during the Hindu festival Ram Navami. The curfew was lifted only a day after Eid.

In the north, in Jodhpur in Rajasthan state, a curfew was imposed on Eid as well when clashes between Hindus and Muslims broke out after a group of Hindus forcibly put up flags of the Hindu god Lord Parashuram in an area where Muslims offer prayers on Eid.

In Jahangirpuri, a poor Muslim neighborhood in Delhi, violence started on April 16, a fortnight before Eid, when members of right-wing Hindu organizations marched past a mosque to celebrate the birthday of the Hindu god Hanuman. In a video that went viral, Hindu men were seen dancing and chanting religious slogans, with many holding swords and tridents, in front of the mosque, leading to clashes with local Muslims. Four days later, the city’s municipal body, run by India’s governing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), demolished shops and houses closer to a local mosque, calling them “illegal.”

After a series of attacks against Muslim communities in India during the month of Ramadan, this year’s Eid al Fitr celebrations were somber.

Sheikh Akbar’s “legally approved” shop selling cigarettes, snacks, and sodas was among those razed. Akbar, 38, said that he had never spent a more “depressing” Eid in his lifetime. After losing goods worth INR 250,000 (US$ 3,248) in the fire, his family is now living on donations from neighbors and journalists. On Eid, Akbar’s wife Rahima cooked only seviyan (a vermicelli pudding), since there wasn’t enough money to buy meat for the festivities.

“I had promised my children to take them out for a city tour, and buy them two sets of clothes for the Eid,” said Akbar, a father of three. “But I could only manage to buy them one set — that too the ordinary ones — and all of us were confined to home on Eid.”

More than 4,000 kms away, in Singapore, Indian migrant worker Mohammad Rafiq celebrated Eid by first going to pray at Kampong Glam’s Fatimah Masjid, a mosque known for its intriguing architectural mix of European, Malay, and Chinese influences. Later, he cooked biryani (a rice dish) and mutton with his friends at the dormitory where he lives.

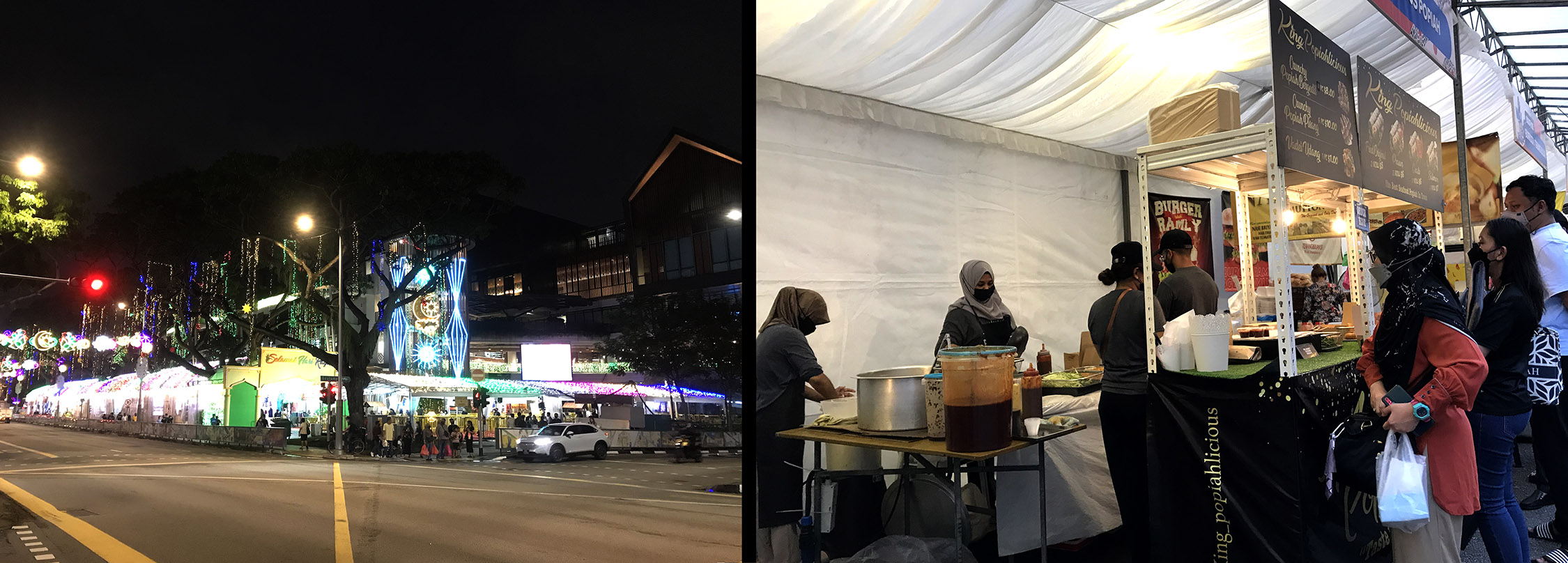

It was actually the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic began that Muslims in Singapore had been able to celebrate Hari Raya Aidilfitri — as Eid al Fitr is called in Southeast Asia — with fanfare, and with friends and family.

“For the past two years, Eid has been very lonely,” said Rafiq. “Praying and celebrating together with friends made it special.”

“This year’s celebrations were special, after two years of not having large gatherings,” echoed Walid Jumblatt Bin Abdullah, social sciences assistant professor at Nanyang Technical University. “Family is so important in the Muslim tradition, and Southeast Asian Muslims, like their counterparts elsewhere, love large Raya gatherings with their extended families. Nothing can replace the face-to-face interactions, the hugs, the tears.”

Contrasting approaches

As in India, Muslims in Singapore are a minority. Yet while both India and Singapore are known for their secular and multicultural ethos, the contrasting Eids this year in the two countries suggest that the tiny city-state of Singapore could teach giant India a lesson or two.

India, under BJP rule, has been ostracizing Muslims on a routine basis by encouraging physical attacks on them over the past eight years; it didn’t spare them even during the holy month of Ramadan this year. Singapore, meanwhile, has been making efforts to project Muslims as an integral part of the country — more so on this recent Ramadan, which the country used as an occasion to restore normalcy after COVID-19 by opening businesses and sending a strong message of inclusion to Muslims.

“In countries like Singapore, where minority rights and culture are being respected, it understands that protection of minority rights is morally right and a prudent strategy for the country’s peace and development,” said Ashok Swain, peace and conflict research professor at Uppsala University in Sweden.

Indeed, Singapore has consciously portrayed Muslims as key to its much propagated “multi-religious” and “multicultural” heritage. This recent Eid, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong even thanked the Muslim community for its “sacrifices” during the pandemic. Lee also visited the local Malays at Geylang Serai a week before Eid. In addition, the government organized virtual tours of Kampong Glam, showcasing the culture of Singapore’s ethnic Malays, most of whom are Muslim.

About 15.6 percent of Singapore’s six million people are Muslim. India’s Muslims make up 14.2 percent of its population, but that translates to nearly 200 million people or more than 30 times the entire population of Singapore.

Muslims make up India’s largest minority group. Swain observed that violence against Muslims in particular in the South Asian country is not new. However, the violence has been “normalized” in the last eight years that BJP has been in power.

“The Hindu rightwing groups’ attack on Muslims on Eid,” he added, “is part of the larger political agenda to divide the country based on hate and fear.”

Swain explained that hate politics and hate crimes against Muslims have brought “high political dividends” for India’s ruling party, which has paved the way for the “systematic and regime-supported target of minority Muslims.”

This is even though Prime Minister Narendra Modi promised “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, and Sabka Vishwas (togetherness of all, development for all, and trust of all)” when he was re-elected in 2019.

At an election rally in February 2022, Modi had also said that the BJP had “freed” Muslim women from the tyranny of triple talaq (instant divorce), and that his government stands with Muslims. Yet he has yet to utter a word in defense of Muslims — or for that matter, India’s other minority groups — whenever they are harassed or discriminated against.

Harassment and discrimination

India’s National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has said that 2,008 cases of harassment of minorities and lower-caste Dalits were registered between 2016 and 2019 across the country.

Sources: House of Lords Library, Ministry of Home Affairs Singapore, Guide to Singapore’s Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act, Islamic Religious Council of Singapore

The northern state of Uttar Pradesh has attained notoriety as far as crimes against minorities are concerned. According to NHRC, victimization and harassment of minorities in the state rose by 137 percent, or from eight cases to 19, between 2017 and 2018.

A December 2018 report by the online media site NewsClick said that in 2018 alone, 70 percent of the reported cases of violence were “bovine-related” and that 75 percent of those targeted were Muslims. The Uttar Pradesh government itself said that from 2017 to 2020, more than 37 percent of the 124 killed in encounters were Muslim. During that period, the state government raided abattoirs and butcher shops — businesses directly linked with Muslims. State police also arrested Muslim men for having romantic affairs with Hindu women, which they called “love jihad,” or an alleged conspiracy to overpower Hindu culture.

Then in late March 2020, hashtags of #CoronaJihad started dominating Indian social media, with posts suggesting that Muslims were the main carriers of the coronavirus in the country.

At the time, many Muslims who attended a gathering organized by the Muslim missionary movement Tablighi Jamaat in Delhi reportedly tested positive for COVID-19. Top BJP politicians began blaming Muslims for spreading the virus. The police charged Tablighi Jamaat’s head with culpable homicide, while people tweeted that “#CoronaJihad” was “more dangerous” than coronavirus, and that both “Corona virus and Quraan-e-virus” were harmful to humanity, making a reference to Islam’s holy book. Some people also called Tablighi Jamaat members “despicable creeps,” supposedly for “spitting out of windows” of the bus taking them to hospital for treatment.

“Superficial” understanding

Around the same time, several Singaporeans were infected at a big religious gathering, also of Tablighi Jamaat, in Malaysia. In commenting on the incident, though, Singapore’s Lee was careful in saying that the issue was not “religion,” but the fact that the virus can spread to many people in crowded settings.

Yet a section of ethnic Malays believes that the Singaporean government has a very “superficial” understanding of the community and is guilty of discrimination as well. For example, Muslim women who are in some public sector jobs that require them to wear a uniform are still not allowed to wear the tudung or hijab (headscarf) at work. “This itself is a systematic discrimination against Muslims,” said Dr. Humairah Zainal, a medical sociologist and associate lecturer at Singapore University of Social Sciences, although last year the government made an exception for nurses.

More recently, a short government video sparked a severe social media backlash from the Malay community. The video showed a boy from a financially strapped Malay Muslim family skipping school to earn extra money. After the parents were informed that their son was missing classes, the mother decided to return to work while the father found a new job. The boy was thus able to return to school and the family moved into a new home, where they celebrated Hari Raya.

To some Malay Singaporeans, the video stereotyped them as people from society’s lower strata; others thought it suggested Malay families can only celebrate Hari Raya when they achieve economic success. The Instagram page Lepak Conversations, which voices concerns of Malay Singaporeans, said that the video had portrayed ethnic Malays in a “reductive and condescending manner.” It added that it was “tiring and hurtful” to have to contend with narratives based on stereotypes and a lens that views the community as “always deficient.”

The government eventually took down the video from YouTube. But it asserted that it had been about “a family’s journey of resilience in facing challenging circumstances, and how mutual support and encouragement could nurture the process.”

Singapore’s Muslim community celebrated Eid al Fitr with joy as the city-state slowly comes out of COVID-19 restrictions.

Humairah was unconvinced, noting that the video showed the parents as unaware of their child’s whereabouts until his teacher talked to them. Said Humairah: “The community is promoted as backward and problematic in a way so that the government is absolved of the responsibility to address systematic gaps that promote inequality. The government doesn’t seem to acknowledge that the real problem is not the shortcoming of individuals belonging to any particular community but an institutional failure to address systemic gaps.”

She also pointed out that some ethnic Malays are given menial jobs in the police force, and are almost excluded in national service sectors such as intelligence, the air force, and commando and artillery units. “There is a perception,” Humairah said, “that Malays may not be loyal to Singapore if there is a war against any Islamic nation in the neighborhood because of their religious affiliation, which may overrun their loyalty toward the country.”

Still, although Malay Muslims have to navigate the complexities of racial discrimination in Singapore, they are not subjected to violence on a routine basis like Muslims in India.

In Delhi, Akbar said that at his shop, he had kept a portrait of Mahatma Gandhi, the father of the nation, who is celebrated for spreading harmony and peace. But he lamented, “The bulldozers didn’t spare Gandhi either.” ●

Sonia Sarkar is an independent journalist who writes about South and Southeast Asia.