|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

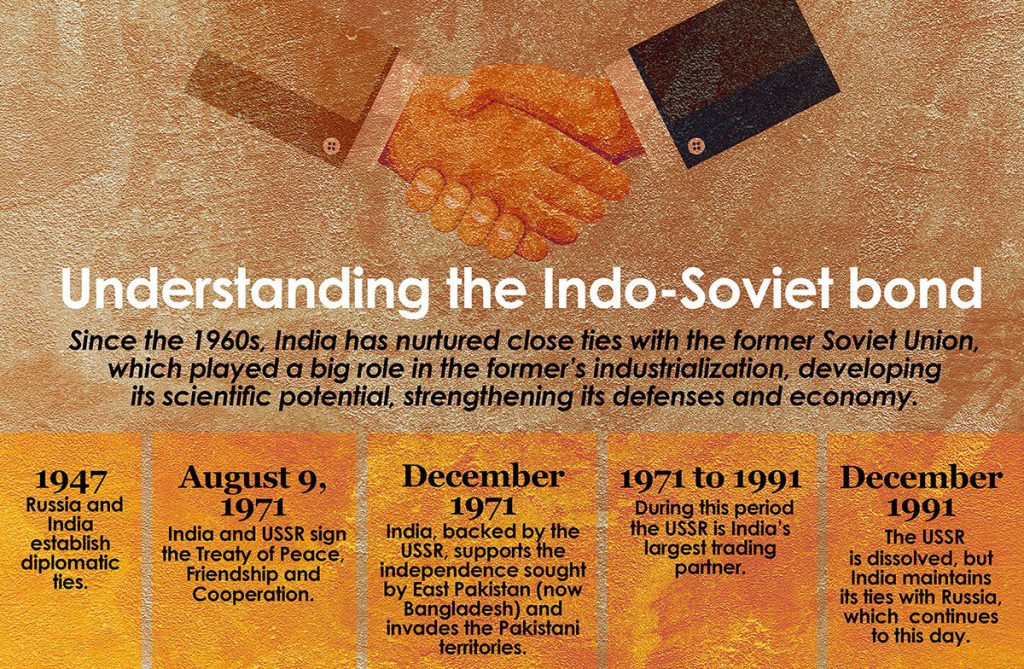

Russia’s brutal invasion into Ukraine, which has led to the death and displacement of millions, has not come without a cost. As Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine border towns and Western powers began to apply economic sanctions in the hopes of quickly making the war unviable, Moscow found itself getting diplomatically isolated — but not without some exceptions, of which the most notable have been China and India.

In keeping with tradition, India has consistently chosen to abstain from UN votes seeking to condemn Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, a stance reminiscent of its abstention when Russia invaded Ukraine’s Crimea in 2014. This position has been met with a great deal of domestic support within India, with #istandwithrussia and #istandwithputin dominating Indian Twitter feeds during the first few days of the invasion. Such feeds were fueled by the public memory of longstanding Indo-Soviet friendship, as well as a legacy distrust of Washington. This can be traced to the failure of the United States to heed India’s calls to isolate Pakistan for crossborder terrorism and U.S. contributions to the crises of Afghanistan, Syria, Libya, and Iraq.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, seen here with Russian president Vladimir Putin and Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2019 (left photo) and US President Joseph Biden in 2021 (right photo). India has long had a history of friendship with Russia, but now also recognizes the benefits of maintaining ties with the West to safeguard its own economic interests.

The rising ethnonationalism in India, moreover, resonates with the Russian narrative of protecting and liberating Russian-speaking populations in Ukraine and its view of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the United States as the true world aggressors. Hindu nationalist elements in India have articulated their support for an “Akhand Russia,” in what is perceived as Russian President Vladimir Putin’s effort at re-establishing the Soviet Union, which had Russia as its command post, and with 14 other republics, among them Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, and Moldova.

“Akhand Russia” is understood to be analogous to the Hindu nationalist vision of re-establishing the Indian nation state corresponding to the borders that existed prior to colonization by the British Empire; that would include all of Pakistan, Bangladesh, Kashmir, and even, by some accounts, Nepal, Bhutan, and Myanmar. Rightwing elements and organizations in India — which have frequently alluded to the ultimate Hindutva goal of creating a Hindu nation that would comprise a “Akhand Bharat” — have chosen to view Russia’s aggression in Ukraine as a necessary means to the same end. Putin’s statements referring to the de-Nazification of Ukraine and the alleged genocide of Russian speakers also, ironically, evoke similar far-right, ultranationalist sentiments among nationalist parties in India — which, incidentally, form the current government.

Sanctions and handshakes

India and Russia have also shared a long history of friendship and reciprocal back scratching, the most prominent being the Russian veto on the UN Security Council resolutions calling for internationalization of the Kashmir conflict on as many as three different occasions, the most recent being in 2019, when India moved to abrogate Article 370 in Kashmir. Russia’s veto obviously earned it major diplomatic brownie points with India. This is especially illuminating when seen in light of Western and UN Security Council actions, which historically have been understood as being inimical to Indian’s perceived security interests in Kashmir, China, and Bangladesh.

India’s aversion to being strong-armed into aligning with the West is therefore not very difficult to understand. Further, India’s need to align with Russia stems from a history of having to forge military alliances with the Soviet Union, when the U.S. alliance with Pakistan and rapprochement with China left India with little choice. Today Russia is India’s main supplier of defense equipment, a relationship that has created a certain amount of dependence, which ensures cooperation and collaboration between the two nations.

As economic sanctions around Russia tighten, Moscow has had to explore innovative methods to continue trade and commerce. To that end, it has offered India heavily discounted crude oil, which traditionally European buyers had purchased before the application of the sanctions. Moscow has also invited Delhi to discuss the possibility of trading in rupee-roubles rather than dollars, which has the intended aim of bringing back into popular debate the worldwide accepted system of petrodollars.

So far, the United States, one of India’s biggest trade partners and sources of foreign investment, has taken a tolerant view of what has been presented as economic compulsions that do not allow India to risk antagonizing Russia. This soft stance is likely due to India’s bargaining power, which stems from its positioning as a counterweight to the Western-perceived threat of China. But India has nevertheless been under pressure from Washington to reduce its trade dependence on Russia and join the Western powers in isolating Russia as a punitive measure for its aggression in Ukraine. While British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s recent trip to India might signal a prioritizing of economic gains over the thus far ideological stand of a rules-based international order, neither the European Union nor the United States have followed suit as yet.

The extent of Washington’s patience may surface soon as India proceeds with talks regarding the possibility of a rupee-rouble agreement, which might be viewed less as neutrality and more of aiding and abetting. U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo has already commented, “Now is the time to stand on the right side of history, and to stand with the United States and dozens of other countries standing up for freedom, democracy, and sovereignty with the Ukrainian people, and not funding and fueling and aiding President Putin’s war.”

Spotlight on rights record

The tightrope walk that India has been forced to undertake is essentially an effort to maintain relations with both Russia and the Western powers while safeguarding its own economic interests. Yet it is a walk that may become increasingly tricky as pressure to condemn Russia mounts, by way of turning the international spotlight on human-rights violations that have occurred under the watch of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Sources: Observer Research Foundation, Britannica, The Tribune

The UN Human Rights Office, for one, has taken cognizance of the ill treatment of those imprisoned in the 2018 Bhima Koregaon case, urging Indian authorities to release the jailed activists on bail. UN Special Rapporteur Mary Lawlor took note of the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act or UAPA, which Modi’s political party has used indiscriminately to crack down on dissenters. Of the individuals that authorities had thrown behind bars, purportedly over the Bhima Koregaon incident, Lawlor said: “These people should not be in jail. They are our modern-day heroes and we should all be looking to them and supporting them and demanding their release.”

Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), meanwhile, have called upon India’s soft power to bring Putin to the negotiating table. It is worth acknowledging, however, the limited effectiveness of appealing for the protection of Ukrainian human rights to a country that has in recent times seen not only an alarming rise in rights violations at home, but also a perceptible shift toward authoritarianism and autocracy. Indeed, the dichotomy in policy as India appeals for peace abroad while violating democratic rights of its own citizens has not gone unnoticed by the international community.

Recently, in a bid to persuade India to change its stance, 21 MEPs wrote to Prime Minister Modi and other Indian authorities, highlighting their concern over the brutal quashing of dissenters and human-rights activists, and making special mention of the Elgar Parishad case, Citizen Amendment Act protesters, and the use of the Pegasus software in illicit surveillance of citizens.

Of India and the Ukrainian crisis, Swedish MEP Jakop Dalunde said: “(It is a) conflict between democracy and autocracies. If India wants to pursue a world order that is based on human rights, it would benefit from Putin’s failure. If it wants to go more toward autocracy, it might benefit from Putin winning. It is up to India to now decide what kind of world order would you like to see.”

The message on the placard from a protest in 2015 still rings true today. India will have to face the injustices that its people suffer as the nation’s leaders are pressured to condemn the atrocities in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

As time wears on and pressure builds, India might find it increasingly difficult to throw its lot in with Russia, especially as India’s own checkered record on human-rights violations is internationalized. While India claimed the UN’s allegations of human-rights violations in Kashmir last year were simply not true and “unwarranted,” it could have a harder time shrugging off such remarks in the future. Any pressure applied by Western powers through questions about India’s conduct in this department may prove to be very uncomfortable for India to defend.

The Indian government’s foreign policy might make it popular at home, but it will have to consider the wisdom of challenging Washington and risking alienating the Western powers upon whom it is dependent for trade, aid, defense technology, and most importantly, protection from hostile neighbors. Placing all its eggs in Russia’s basket could prove to be a tenuous choice, especially when it comes to national anxieties regarding China.

India might succeed in laying low for now and abstaining from future votes on the subject, secure in the knowledge that its membership in the UN Security Council comes to a close at the end of 2022. But that will not necessarily provide immunity. At the end of the day, India would do well to clean up its own house and make sure it doesn’t fall off the tightrope that international relations have now become. ●

Insiyah Vahanvaty is a socio-political commentator with an interest in minority rights, human rights, democracy, gender parity and secularism.