|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

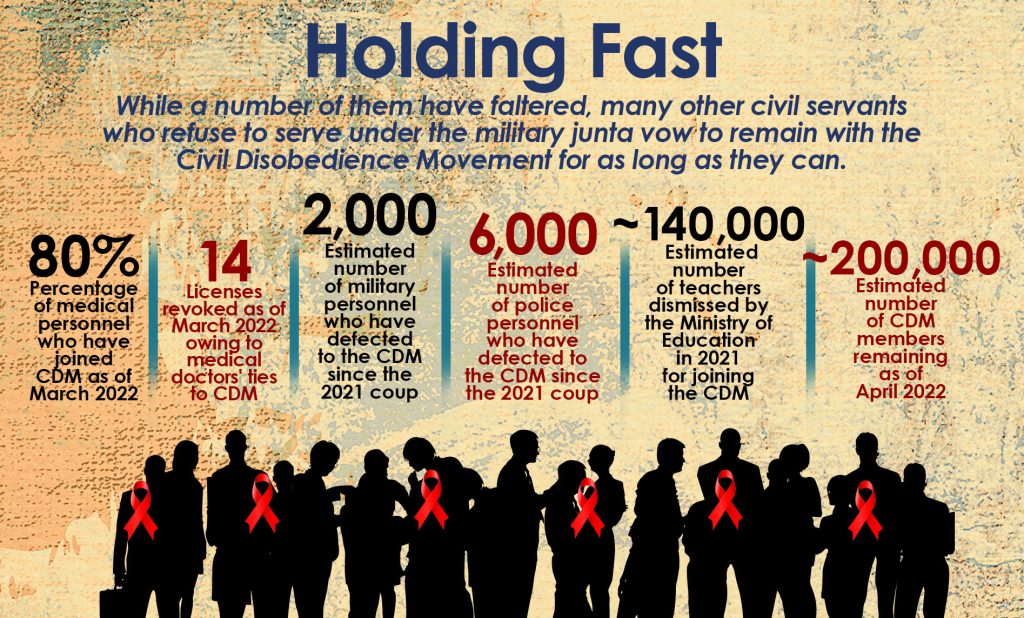

By most accounts, the movement began with doctors and other health workers who pinned red ribbons on their clothing and stopped going to work. Then the teachers followed suit, as did diplomats, railway workers, and staff from the energy and other departments. Today, more than a year after Myanmar’s military staged a coup, many of the country’s civil servants continue to be absent from work or have left their posts altogether, as a show of defiance against the junta.

These civil servants initiated Myanmar’s Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) almost as soon as they realized that power had changed hands by force in February 2021. They issued statements condemning the coup and demanded a return to democracy. Since then, they have also often been at the forefront of peaceful rallies and other activities organized as protests against the military regime.

Just a little over a month after the coup, six academics even nominated Myanmar’s CDM for the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize, most probably to the irritation of the junta.

Civil servants call on their fellow government employees to join the Civil Disobedience Movement in Yangon in February 2022. (Photos from DVB and citizen journalists)

What has made the most impact on the military, however, is the fact that many civil servants have been missing from work, disturbing the workings of government. This has prompted junta chief Min Aung Hlaing to describe CDM as “an activity to destroy the country.” While the military has estimated that some 30 percent of the civil service has joined the CDM, observers say that the figure is closer to 55 percent.

Not surprisingly, the military has driven “disobedient” civil servants and their families out of their state-provided housing, even as it has been hunting them down. In March 2021, some 1,000 personnel of Myanma Railways and their families were evicted from their homes after they were found to have joined the CDM. A worker from the government construction department also recalls, “I and my old grandmother had to leave my housing in three days, and it was a bit difficult to find a new house for an ordinary civil servant who earned a low salary.”

Wrong people at the top

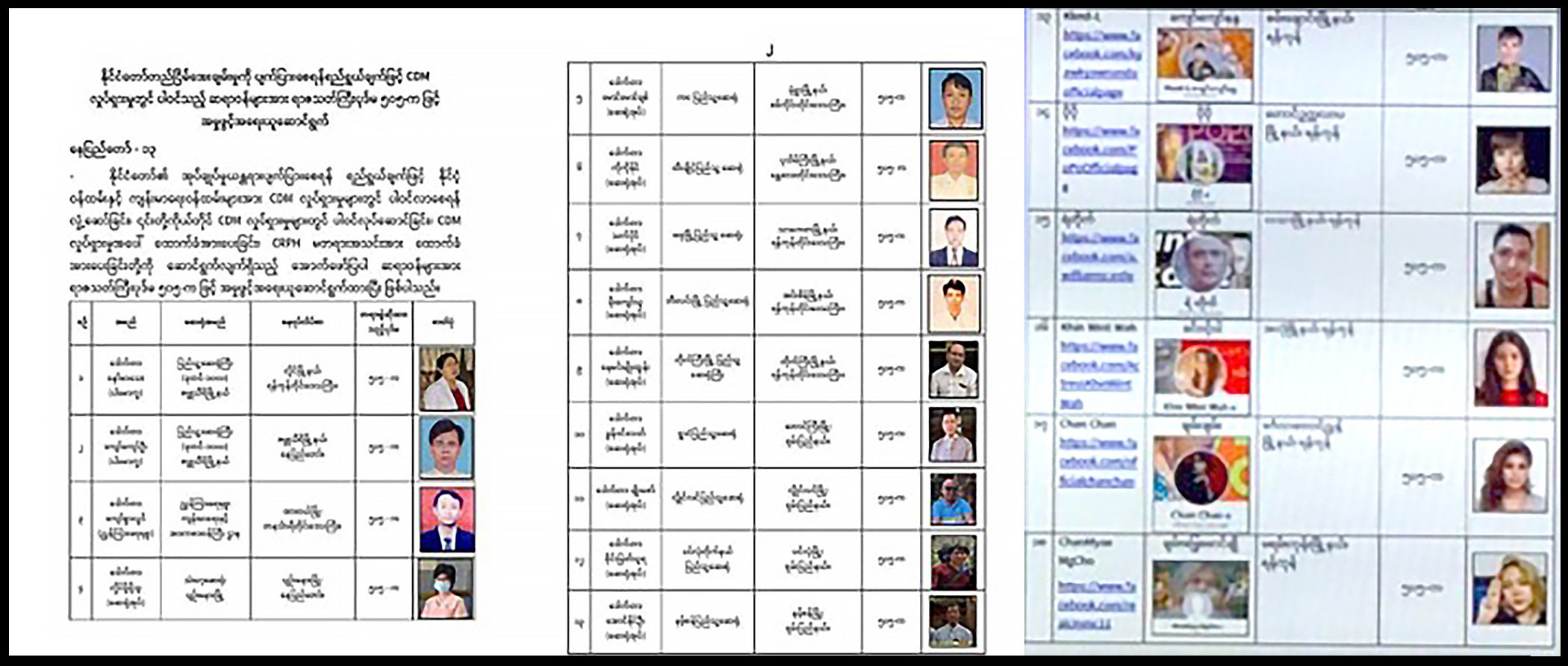

The military wants the civil servants back so that the government can run normally. It has threatened those unwilling to return with arrest — and worse. The people caught by the military are slapped with charges of having violated Section 5050a of the Penal Code, which carries a maximum sentence of two years in jail and is non-bailable. The junta had amended the section, making any hindrance to the performance of the duties of government workers illegal.

This has made some civil servants trudge back to their offices. But most times, the junta has not been getting the response it wants. Says a medical worker who is part of the CDM: “I can no longer work under the military regime. I used to give medical care to the refugees in the Kachin conflict area and I know how the military can be cruel. That is why I decided to leave my beloved office since I cannot work under a brutal government.”

Teachers and state education personnel also felt it was an affront to them when the military said that “voter fraud” was among the primary reasons it decided to take power from the elected civilian government of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. Staff from state schools worked as volunteers at the polling stations during the 2020 elections, which delivered another landslide victory for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy.

“In the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, we volunteered at the polling stations and we were sure there was no voter fraud during the elections,” says one teacher who is also now with the CDM. “Seizure of power because of supposed voter fraud is like punching us in our faces.”

For most, however, the reason for their refusal to return to their government jobs is simple: they will not take any orders from an illegitimate regime.

To date, some 125,000 teachers have been suspended from their posts. Many of them, along with doctors, nurses, and other civil servants gone CDM, have also been charged and arrested, while others are now on the “wanted” list. As a result, many CDM public servants do not stay in one place for long and are constantly on the move. They have also elected to have little or no contact with their loved ones. Says a CDM civil servant: “I try to have less communication with my parents because my communication with them might put them in trouble and I do not want that.”

Constant anxiety, gaps in government services

For sure, their lives have only gotten harder. Even those who find a secure place for themselves worry constantly about their families. Some have admitted that they suffer psychological trauma and mental distress. One government health worker who is on the run says, “I do not want to think about the future. If I think of that, I cannot sleep and my tears fall. I have no idea when I will return to my office and meet my friends and family.”

They are also hardpressed in finding some means to support themselves. There has been talk of the junta having a database of those who are part of the CDM, and private companies are wary of hiring someone who they suspect is part of the movement. A former civil servant says, “Though we were encouraged to do CDM at first, we cannot even get a single job now. So, many of us have turned to selling food and cloth. But if our ventures become popular, they will attract the attention of junta forces and we will be arrested. So we just want to work in a business with a low profile. Our lives have become a mess.”

So has the delivery of government services, apparently. The junta has increased the retirement age for civil servants from 60 years old to 62 years old in a bid to keep the wheels of government turning. It has also been replacing the missing staff in government offices without making the new recruits go through the usual vetting process — and ending up with personnel who are not up to the task.

Source: Myanmar Now, Frontier Myanmar, Radio Free Asia

One clinic staff and a recent patient at the General Hospital in the Ayeryawaddy Region says, “After the removal of many CDM staff, service has been less reliable in the public hospitals and there is also the presence of soldiers in the hospital compound. That is why people usually go to the private hospitals and community clinics instead.”

Adds the staff, “Based on my experience, the capacity at the General Hospital is really bad and there is still a shortage of medical staff and many services that were offered before are still missing. The medical officers there are also not friendly anymore.”

A father of a 13-year-old who goes to a government middle school also tells Asia Democracy Chronicles, “First and foremost, I am worried about my son since there have been explosions near schools across the country. There were not sufficient teachers in schools before the coup and that situation became worse after the CDM began. Many of the qualified and good teachers are not in the schools anymore. When I talked with my son, he said the teachers do not teach well in schools. So I am indeed thinking about moving my son to a private school.”

Longest CDM yet

Yet most people do not complain as more civil servants leave their posts and join the CDM. In some areas, however, the government workers still at work have been threatened by people identifying themselves as resistance fighters to leave their jobs, or else. Some of the soldiers who have become deserters to be part of the CDM may have also been lured by the promise of being granted asylum by the likes of Australia.

Still, there is little doubt that most of the civil servants who are choosing to stand with the people of Myanmar are doing so because they want the leaders they chose to be the ones holding the reins of government. They want democracy and their rights restored. According to a CDM government health worker, they will not return to work as long the power remains in the hands of the junta. They are convinced, says the health worker, that they have no future until “the junta is taken down.”

The authorities issued warrants of arrest of civil servants charged for their participation in the Civil Disobedience Movement. (Photos from Eleven and MRTV)

Several CDM public servants have also found work with the National Unity Government, the shadow civilian government made up of members of parliament who were elected in 2020 and other pro-democratic forces. One CDM civil servant from the executive branch says, “I was invited to work for a ministry of the National Unity Government. Though there is no salary, I happily work for them because I want to finish this revolution as fast as possible and return to my office.”

And so what has become the world’s longest-running Civil Disobedience Movement goes on. A CDM teacher says, “We chose this path and will continue on it until the end. We have already sacrificed a lot, and we have nothing more to lose.” ●

Jesua Lynn is an independent researcher and peace-education trainer. He has authored and co-authored more than four publications on Myanmar in the fields of human rights, hate speech, youth activism, and peace-building.